[Editor’s Note: The following are summary reports from select presentations given during the two-day Medicine & Science in Ultra-Endurance Sports Conference held before the 2015 Western States 100.]

[Editor’s Note: The following are summary reports from select presentations given during the two-day Medicine & Science in Ultra-Endurance Sports Conference held before the 2015 Western States 100.]

New Knowledge from Continued Western States 100 Research: GI Symptoms during Ultramarathons

Kristin J. Stuempfle, PhD, FACSM, ATC

Gastrointestinal (GI) distress is the number-one reason runners drop from 100 milers. The etiology of this GI distress is, however, not well defined. One hypothesized factor is the GI tract gets a much smaller percentage of the blood the heart pumps during exercise. This decreased blood flow results in decreased motility (causing heartburn, stomach bloating, nausea, and vomiting) and increased intestinal permeability (which causes endotoxemia). Endotoxemia, she says, is when molecules, which are normally only in the GI tract, make it into the blood. She gave the example of lipopolysccharides (LPS). When LPS make it into the blood, they release soluble cluster differentiation 14 (sCD14). Last year at WS 100, they were able to measure the amount of sCD14 released into the blood (through a capsule 30 participants swallowed pre-race).

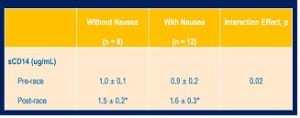

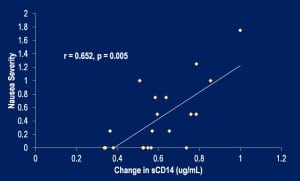

Runners with nausea had a greater increase in sCD14 (a marker for endotoxemia).

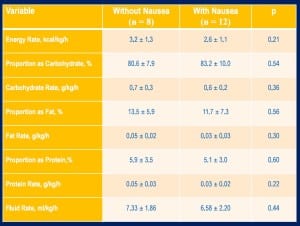

They also found, the higher the CD14, the more severe the nausea.  They did not find a significant association between core temperature, race-nutrition composition, or hydration status and the development of nausea while racing*. Tables of the significant and non-significant findings are shown below.

They did not find a significant association between core temperature, race-nutrition composition, or hydration status and the development of nausea while racing*. Tables of the significant and non-significant findings are shown below.

[*Author’s Note: A major issue in ultramarathon research is small sample sizes. This is important to keep in mind because when the speakers said they “found no significant correlation,” they might have indeed found one if they had had enough participants (enough statistical power) to detect it. If a study does not have sufficient statistical power, it can’t say for certain “there is no correlation,” but if a correlation is found, they know that to be true; or at least if the p value is <0.05, there is less than a 5% chance that the correlation is due to chance. Research from small studies tends to report Type II errors, which means they say something is “not significant” even though they cannot say for certain it is not significant. In the rest of this article, an *asterisk will be used to indicate this situation.]

The markers of inflammation C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) were also not significantly associated with nausea*. Interestingly, core temperature was maintained between 38 and 39 degrees Celsius for both groups of runners. Finally, there was no significant difference in body-weight change between those with nausea and those without.

Questions addressed by the presenter from the audience:

1. Can you recommend treatment or prevention? She mentioned slowing down and decreasing exertion and increasing fluid intake as possibly effective methods of prevention.

[Editor’s Note: Kristin J. Stuempfle presented at last year’s conference. This is the summary of her 2014 presentation.]

Psychological Predictors of Performance in an Ultramarathon

Dolores A. Christensen, MA

Ms. Christensen is doing her doctoral dissertation on the psychological processes of 50- and 100-mile ultramarathon runners. In her research, she looked specifically at demographic, physiological, and psychological factors and how they related to finishing times at Western States. She was focusing mostly on psychological factors since little is known about their impact on performance.

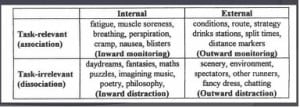

Ms. Christensen’s study from WS 100 in 2014 included 121 runners. The mean WS 100 finishing time among participants was 23:44, mean age 41.5 years. Through multiple-regression analysis, they determined that 10% of the variance in finishing times was due to psychological factors. Average weekly mileage was the best predictor of finish time. Internal distraction did not help with performance, but inward monitoring, outward monitoring, and outward distraction all seemed to positively impact finishing time. These terms are explained in the figure below:

Basically, she concluded, doing maths, puzzles, and poetry in your head won’t help your performance. :)

The following factors were either not associated with performance or they did not have the power to show an association*: age, sex, number of 100 milers run, length of longest run in the last three months, mental toughness, mindfulness, and perception of pain. Additional fun facts from the talk: In the three months up to the race, runners’ mean longest long run was 92 miles (meaning that many of them must have run a 100-mile race somewhere in the three months ahead of WS 100) and average weekly mileage was 62.

New Knowledge from Continued WS 100 Research: Fact and Fiction about Sodium and Hydration

Martin D. Hoffman, MD, FACSM, FAWM

Exercise-associated hyponatremia (EAH) research started at WS 100 in 2008. In 2008 (which was actually at the Rio del Lago 100 Mile, due to WS 100’s cancellation that year), 51% of runners were hyponatremic. The incidence of hyponatremia at WS 100 has dropped linearly since that time to under 10% last year. Those who become symptomatic from hyponatremia are the ones who have gained weight (shown by research from Dr. Timothy Noakes and Hoffman).

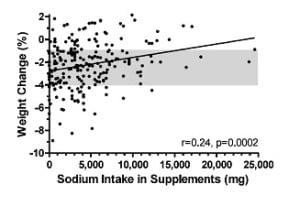

The more sodium you intake, the more you weigh by the end of the race. So there is a suggestion that sodium helps prevent weight loss. The runners with the highest amount of salt tab supplemenation took an equivalent of 72 S! Caps.

The more sodium you intake, the more you weigh by the end of the race. So there is a suggestion that sodium helps prevent weight loss. The runners with the highest amount of salt tab supplemenation took an equivalent of 72 S! Caps.

Those not using supplements and drinking to thirst had greater weight loss, but they lost an appropriate amount of weight for running 100 miles. Those drinking beyond thirst/taking sodium maintained a higher weight than is deemed appropriate by Dr. Hoffman.

There was no relationship found between sodium intake and the development of muscle cramps. There was also no suggestion that sodium supplements prevented nausea or vomiting.

Those who are hyponatremic tend to gain weight or not lose weight. There was a weak relationship between blood sodium and total sodium supplements taken. In terms of total sodium intake, the people who were hyponatremic had a total sodium intake around the mean of all of the runners.

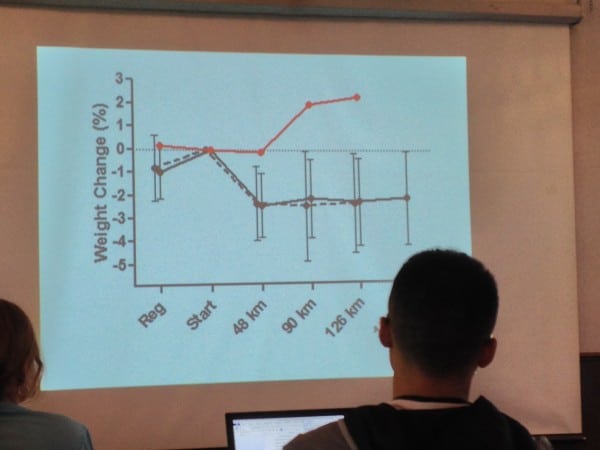

Is too much sodium dangerous? He presented three cases of severe, symptomatic hyponatremia where all runners had taken “excessive” sodium supplementation. Brian Morrison took 7 grams of supplemental sodium and had severe symptomatic EAH by the end of the 2006 WS 100; he had to receive assistance in getting around the track to the finish line because he was so symptomatic, and was eventually disqualified. Another case example of an ultrarunner running rim-to-rim-to-rim in the Grand Canyon: he took >6.5 grams of sodium, finished the run, developed mental-status changes, and emergency medical services was called. He drank over 9 liters and overhydrated due to thirst stimulated by excessive sodium intake. In a third case, at the 2013 WS 100, a man developed seizures after mile 90. He had taken >8.5 grams of salt, was thirsty, his weight was rising, and he developed severe hyponatremia. Below is a graph showing the race weights of this runner:

Photo: Tracy Høeg

Conclusions:

Sodium supplementation should not be the sole prevention for EAH. Salt supplementation enhances body weight beyond what is appropriate and excessive supplementation can be dangerous because it stimulates thirst. There was no relationship between salt intake and the development of cramps or nausea and vomiting.

Avoid overhydration. Drink to thirst. Avoid excessive sodium supplementation.

Questions addressed by the presenter from the audience:

1. How much sodium is “excessive?” Dr. Hoffman believes you can get adequate sodium through food for events of 15 to 30 hours in duration. Multiple-day events may be different. He suspects that excessive sodium intake during training will interfere with your body’s natural regulatory mechanisms and he advises against it.

2. Should we monitor weights during races? There are too many runners who gain weight and who aren’t hyponatremic, so it is not a good diagnostic tool. As of this year at WS 100, there will no longer be the recording of weights on the course. Race workers will only get a pre-race weight.

[Editor’s Note: Martin Hoffman presented at last year’s conference. This is the summary of his 2014 presentation.]

New Knowledge from Continued WS 100 Research: Is Dehydration and Kidney Injury a Real Concern?

Robert Weiss, MD

Dr. Weiss is the medical director of the WS 100 and a professor of Nephrology at the University of California-Davis.

Abnormal kidney lab values are very common following an ultramarathon. (Dr. Weiss cited 38 to 80%, as measured by serum creatinine levels.) Most of these are simply abnormal labs and do not indicate real damage to the kidneys. For example, runners are found to have very high post-race levels of creatine-kinase (CK). (See this study.) You are more likely to have abnormal labs if you are dehyrdated, hyperthermic, or have taken nonsteriodal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as Ibuprofen or Aleve.

Permanent kidney damage, or acute tubular necrosis (ATN), is most often caused by rhabdomyolysis/“rhabdo:” when muscle breaks down and the broken-down tissues are released into the blood. These break-down products (particularly myoglobin) are harmful to the kidneys.

How do you diagnose rhabdo in a race? Ask about muscle cramps and color of the urine. If you see someone with yellow urine, you are less concerned for rhabdo, but cola-colored urine is more indicative of rhabdo. (In a urinalysis, you will have a heme-positive urine dipstick with very few red blood cells.)

Treatment for suspected rhabdo: Give fluids 100 milliliters bolus x 3, avoid potassium. Most important to get the athlete to a hospital, especially if there is also a concern for hyponatremia (because you won’t want to give fluids to someone with hyponatremia).

NSAID-induced acute kidney injury: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) medications, such as Ibupforen and Aleve, inhibit prostaglandins and can lead to kidney damage in runners and non-runners alike. NSAIDs decrease blood flow to the kidneys. If you are dehydrated to begin with, blood flow to your kidneys can get dangerously low and kidney cells die as a result. It is dose dependent: the more Ibuprofen you take, the more likely you are to have kidney damage.

Bottom line: Don’t take NSAIDs during a race.

A small study of 16 runners showed that if you have one episode of race-related kidney injury (abnormal kidney-function labs following a race), you are not more likely than other runners to have it again. Basically one episode does not mean you can’t run another race. [Author’s Note: The case may not be the same for rhabdomyolysis.]

[Editor’s Note: Robert Weiss presented at last year’s conference. This is the summary of his 2014 presentation.]

What is Really Known About Post-Exercise Recovery Methods?

Natalie Badowski Wu, MD

Natalie Badowski, MD, recently completed an emergency medicine residency at Stanford University. She also is a competitive runner and triathlete. She talked about recovery from training and racing, not from injury. She reviewed the research behind the standard exercise recovery methods of rest, ice, and compression. (She didn’t cover elevation.)

Rest:

Active recovery (low-intensity workouts) compared with rest appears to promote faster lactate clearance in cyclists (Ahmaldi, 1996) and improved power output in subsequent intervals (Ahmaldi, 1996). Similar results have been found in skiing (White 2015), cycling (Lopez, 2014), and strength training (Lopes, 2014). In summary, active recovery promotes lactate clearance and return to muscular power after anaerobic efforts compared with rest.

Cryotherapy:

Water immersion, ice baths, ice massages, etc. In rat studies, there was reduced muscle damage and inflammation at 24 hours, but a subsequent study found after two to four weeks, there is delayed muscle regeneration after cooling. One human study found longer time to failure among runners who are cooled to 8 degrees Celsius before immediate subsequent exercise. There is a lot of bias in human studies and none of the studies are blinded.

Compression:

There are two types of compression stockings: uniform and graduated. Among runners, a decreased lactate level and higher calf tissue oxygenation was reported with with graduated compression (Berry, 1987), but no change in running performance has been found (Menetrier, 2011). Compression has been found to cause a reduction in delayed-onset muscle soreness, but no difference in a time trial. In cycling, no difference in performance has been found. In strength exercise, the highest-pressure compression produced the lowest levels of fatigue.

Pneumatic Compression:

Most studies have been done in a hospital setting. The three studies in exercise have been non-conclusive and have found no benefits except possibly a benefit in increased lactate clearance.

Massage:

Provides no significant benefit in performance or power but significantly decreases fatigue and muscle soreness (Dawson, 2004; Robertson, Farr, 2002). Serum myoglobin has been found to be increased after a massage (possibly a marker of muscle damage).

Summary:

Active recovery has been the only recovery method found to improve performance. Other methods provide subjective and physiological benefits. There may be harm from icing, and there is a concern about muscle damage from massage.

The full citation for all of the studies mention can be found in this slide show.

Blister Management

John Vonhof, EMT-P

Dr. Hoffman introduced John Vonhof by saying his book, Fixing Your Feet, is the best guide available for foot care during ultramarathons.

This talk was mainly given for race directors and aid-station workers, although there were many pieces of advice that runners will find useful.

For maceration, clean and dry the feet, put powder on the feet, allow the feet time to dry, and put clean socks on.

His recommended moisture-controlling agent is zinc oxide. Desitin is the agent with the highest concentration of zinc oxide (40%) you can buy and what he recommends.

For blisters, there is an increased risk of blisters with moist, thick, stiff skin. You must have running socks that allow easy movement of the sock over your skin.

For blister prevention, he recommend the ENGO patch, which is placed on the inside of the shoe, wherever the problem area is. It is strong and slick. Shoes can’t be wet when applied.

For the care of blisters once they have formed, if you have a blister and want to continue the race do this (or have someone do it): Clean the skin, lance the blister and get the fluid out, clean again, put zinc oxide over the top or antibiotic ointment. Apply benzoin to area to be taped. Then tape the area using strength tape/kinesiology type tape (example TheraTape). He does not lance blisters at a finish line, only during a race. At the finish line, he recommends Epsom salts.

Tips for lancing: use alcohol wipe to visualize the fluid, use #11 scalpel (puncture holes can close back up) and make more than one opening.

Tips for taping: Apply benzoin to skin before taping. Kinesiology tapes form to fit the foot. Be sure the tape job forms to the foot and that there are not wrinkles. Here is a picture of a good tape job:

Note how well the tape forms to the foot and how there are no wrinkles!

Questions addressed by the presenter from the audience:

1. What about duct tape? No because it doesn’t form to the shape of the foot.

2. Injini/five-toe socks? Says they are excellent for people with frequent toe issues.

3. Preventive taping? Good idea with kinesiology tape the night before. Holds up for over 48 hours. He does this for the Badwater participants.

More questions? He can be reached by email at [email protected] or at his website.

Ultramarathoner’s Eye

Tracy Høeg, MD, PhD

Tracy Høeg recently completed a PhD and post-doc at the University of Copenhagen in Ophthalmology. She is currently a resident physician in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at the University of California-Irvine.

Dr. Høeg at the 2014 WS 100 measuring corneal thickness in a fellow volunteer. That year no runners experienced vision loss, so they were not able to document examination findings.

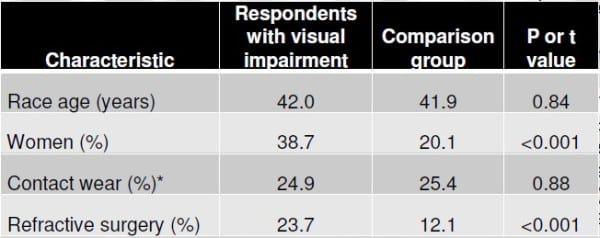

Two years ago, essentially nothing was known about ultramarathon-related visual impairment, except that it happened to approximately 3% of 100-mile race entrants. This type of vision loss also happened to the director of the conference, Marty Hoffman. Dr. Høeg, Dr. Hoffman, and an optometrist colleague set out to explore this entity through a web-based survey, including 173 ultrarunners that had experienced ultramarathon-related vision loss. They learned that it was self-limited (tended to resolve within a few hours and no less than 48 hours), occurs over the full range of ambient temperatures, and is significantly associated with a history of refractive surgery.

Graphic from: From Høeg TB, Corrigan GK, Hoffman MD. An investigation of ultramarathon-associated visual impairment. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015 Jun;26(2):200-4. doi: 10.1016/j.wem.2014.10.003. Epub 2015 Feb 26.

However approximately three quarters of the participants had never had refractive surgery. But those who had also experienced vision loss more frequently. It was also significantly linked to being female, but that may be because females are more likely to take surveys than males.

Of those participants who had an eye examination while vision loss persisted, all were found to have corneal edema, except two, who had corneal damage from contact lenses. This type of vision loss does not appear to have any long-term visual consequences. Exercise-related corneal edema has also been documented in cyclists. Dr. Høeg says they are hoping to collect more data from runners who have had an eye examination and/or photographs of their eyes while experiencing ultra-related vision loss. Please contact Dr. Høeg at [email protected] if you have pictures, examination records, questions, or concerns.

Acute Respiratory Issues in Ultramarathon Runners

Geoffrey Kurland, MD

Geoffrey Kurland, MD is a Professor of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of University of Pittsburgh.

Many runners are incorrectly diagnosed with exercise-induced asthma/bronchospasm (EIB) when they actually have vocal-cord dysfunction (VCD). Below are descriptions Dr. Kurland gave to help delineate the difference between the two:

Exercise induced asthma/bronchospasm (EIB) occurs after 10 to 15 minutes of exercise. Runners wheeze when they breathe out. Symptoms tend to gradually increase and then, if they can keep going, symptoms get better. (You can “run through your asthma,” he says.) EIB more commonly occurs in cold, dry air and actually worsens after exercising stops. EIB can be prevented with albuterol prior to exercise. There is an increased prevalence of EIB in elite endurance athletes, though it is not clear why. Diagnosis of EIB made based on history. Treatment: include a warm-up before workouts, protect the airway from cold exposure in cold temperatures (face mask, Buff, etc.) during runs, use a Beta-2 agonist inhaler (such as albuterol) prior to running, and use long-acting asthma medications on a daily basis.

Vocal-cord dysfunction (VCD) is common and is often mistaken for exercise-induced asthma/bronchospasm. There is obstruction of airflow on breathing in rather than exhaling (as opposed to asthma). VCD occurs with exercise or stressful situations. It typically presents in high-achieving, athletic, and intelligent females. (He is not sure why, but says these are the majority of patients he sees with it.) VCD does not respond to albuterol. Athletes who suffer from VCD complain of tight breathing localized to the neck. When they stop exercise, the difficulty breathing is gone and goes away suddenly. Treatment: understanding is key; speech therapists help teach patients to get their vocal cords to relax. Medications do not work.

Management of the Seriously Ill or Injured Ultramarathon Runner

Jeremy Joslin, MD

Dr. Joslin is an assistant professor in Emergency Medicine at the Upsate Medical University. He is also the medical director of Jungle Marathon, Grand to Grand, Global Limits, Desert RATS, Syracuse Ironman, and Empire State Marathon. This talk was mainly directed at health-care workers at races, but had some useful information for runners about the medical conditions he sees in ultramarathons.

Exercise-associate collapse/exercise-associated postural hypotension (EAC/EAPH):

This happens after crossing the finish line. The muscles in your calves have a major role in helping pump blood back to your heart from your legs. When these muscles fatigue, you can have less blood returned to your heart and a drop in your blood pressure. When this happens, your brain senses it is receiving too little blood and the automatic reaction is to faint, bringing you to the ground, which then brings sufficient blood to your brain. This condition is not regarded as dangerous as long as the runner is able to get their feet up above the level of their head (by lying down in so-called Trendelenberg position). To prevent EAPH, runners can get into this position within a few minutes after crossing the finish line. This condition is believed to be due to calf-muscle fatigue and not related to dehydration as it does not correlate with hydration status. He mentioned that runners with a lower blood pressure to begin with may be at higher risk for EAPH, but did not present data to support this.

[Author’s note: I have experienced this upwards of five times following ultras and, now that I lie down with my feet up shortly after finishing, I have been able to prevent its recurrence.]

Cardiac collapse:

Caused by arrhythmias/cardiac ischemia. Very uncommon (1/100,000 in the marathon distance), but should be suspected in a runner who collapses while running. He referred to this article in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Dehydration:

The concern about this in single-day races is overemphasized. It is very unlikely and should not be diagnosed unless it is absolutely certain. It has contributed to drinking too much during races and has contributed to the development of the much more dangerous exercise-associated hyponatremia.

Hyponatremia:

Low blood-sodium level. This was not discussed as it had been discussed by Dr. Hoffman (see above summary), but is associated with excessive fluid intake while racing. Treatment should be with 100 milliliters IV 3% saline. Blood sodium can now be measured during races with an iSTAT machine.

Heat stroke:

End organ injury in the setting of heat stress. It is uncommon but life threatening. If there are mental-status changes but sodium is normal, it is likely to be heat stroke, especially in warm temperatures. Do not rely on check of runner’s temperature alone; the runner’s temp may have started to go down. Treatment: Cool patient; use rivers, creeks, pools, ice machines. Find sheets or a blanket and soak in water, and wrap the participant in the sheets so they can loose heat through vaporization.

Anaphylaxis:

Runners with a history of anaphylaxis need to carry epinephrine with them. But runners also develop anaphylaxis while racing without a history, so medical personnel also need to have epi available.

Blisters:

Runners should be educated about how to prevent and fix their own blisters and feet problems.

Exercise-associated gastroparesis:

Due to decreased blood flow to gastrointestinal tract, you are not able to effectively digest food and fluids. This is more prevalent and more of a problem in multi-day races. Treatment: his favorite treatment is the anti-emetic medication, Zofran (Ondansetron).

Dr. Joslin can be reached at [email protected].

[Author’s Note: Dr. Joslin did not mention hypothermia, but a case of this was presented during the abstract presentations. It occurred during a 100-mile run in 41 degrees Fahrenheit, but the windchill was 18F and it was pouring rain. Life-threatening hypothermia developed insidiously in an experienced ultrarunner, essentially without warning signs. He developed mental-status changes and muscle movements resembling seizures. Because they were in the wilderness, he had to be wrapped in a blanket and carried two miles to a fire station where he was driven an hour to a hospital. At the hospital, his temperature was still low enough to receive the diagnosis of severe hypothermia. This case was presented by Dr. G. Clover.]

Case Study: Overtraining

Tracy Høeg, MD, PhD

This talk was given by Dr. Høeg, introduced under “Ultramarathoner’s Eye.”

The case of a 30-year-old female was presented. She was a top-10 WS 100 runner who, three months after completing the Grand Slam of Ultrarunning (four 100 milers in one summer), reported debilitating fatigue, inability to run or walk, insomnia, weight loss, and palpitations. Her initial diagnosis was hyperthyroidism, but she then began to gain weight and her thyroid normalized. She saw a sports-medicine physician who diagnosed her with severe iron deficiency. She received iron infusions, her iron level normalized, and she initially had a minor improvement in symptoms, but then relapsed into immobility and insomnia. Additional info about the case: She was part of the FASTER study and thus consuming only about 20% carbohydrates in her diet (though according to study leader Dr. Phinney should have been <10%) prior the development of her symptoms and is still on that diet. She had also moved to altitude from sea level six years prior. After nine months of not being able to run, and barely being able to hike, she was referred to Dr. Høeg.

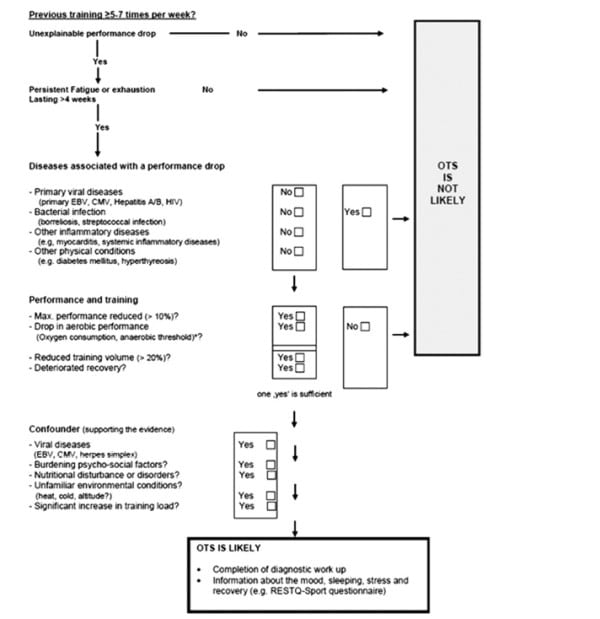

Dr. Høeg gave a review of Overtraining Syndrome based on the consensus statement of the European College of Sports Science and the American College of Sports Medicine. (The PDF can be downloaded here for free.) Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) is defined as “A ‘sport-specific’ decrease in performance together with disturbances in mood. This under-performance persists despite a period of recovery lasting several weeks or months.” It is a diagnosis of exclusion and a flow chart for its diagnosis in athletes is shown below. There are currently no useful blood tests in the diagnosis of OTS that don’t require exercise testing during their measurement. Maximal lactate concentration is found to be lower during exercise and the hormone ACTH does not rise as expected on a second bout of maximal exercise in OTS. Maximal heart rate during exercise is also suppressed. Cortisol measurements, resting heart rate, and heart-rate variability have not been found to be reliable in the diagnosis of OTS.

Chart from: Meeusen R, Duclos M, Foster C, Fry A, Gleeson M, Nieman D, Raglin J, Rietjens G, Steinacker J, Urhausen A; European College of Sport Science; American College of Sports Medicine. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science and the American College of Sports Medicine. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013 Jan;45(1):186-205. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318279a10a.

OTS is often complicated with additional conditions, including depression 80% of the time. Dr. Høeg gave several other examples of OTS in ultramarathon runners, which demonstrated that full recovery can take years.

As OTS is currently essentially untreatable, prevention strategies were discussed. The athlete in the case was given a realistic prognosis, encouraged to increase carbohydrate intake, find alternative non-endurance training, and receive treatment for co-existent psychiatric conditions.

Questions addressed by the presenter from the audience:

1. Additional workup was recommended by clinicians in the audience. Dr. Høeg had suggested the patient receive more of a cardiac work-up and a viral-disease workup as per the diagnostic flow chart. However the patient was not interested in these tests at the time due to their costs and her out-of-pocket expenses. This is a real issue for athletes with suspected OTS, still wondering if their diagnosis is correct.

Case Studies: Depression and Endurance Sports

Nikki Kimball, PT; Rob Krar, Pharm D; and John Onate, M.D.

The lectures series ended with far and away the most moving presentation of the two days. Dr. Onate, a psychiatrist at the University of California-Davis, brought ultrarunners Rob Krar and Nikki Kimball to the conference to share their own experiences with running and depression.

Photo: Tracy Høeg

Rob Krar:

Rob said he has suffered from depression the last two decades. He defines depression as “sadness without purpose.” He says the relationship between running and depression is very complex: “Depression and running go hand and hand and determining cause and effect has been a mystery so far.” He says it is “a stretch to say I love running.” However, he loves the feeling he gets after he has run. He says he loves the very dark place he goes to in his head at the end of a very hard ultramarathon. He describes this as extremely cathartic. Prior to meeting his wife, he felt depression carried a social stigma. He currently seeks to discover coping mechanisms so he doesn’t negatively impact the lives of others. However, he does not want to take medications and has never taken medications for his depression. (Of note, he is a pharmacist.) He ended with three thoughts: know you are not alone, find someone to talk to, and believe you can learn from your darkest hours.

Photo: Tracy Høeg

Nikki Kimball:

When Nikki graduated from college, she trained full time in biathlon with results putting her within close reach of making the American Olympic team. She was at a happy, stable period in her life when she suddenly started sleeping 18 hours a day and lost over 30 pounds in three months. She says that she would have died from it had she not had a roommate in college who had been so open about her own depression. Nikki said she was fortunate that the first doctor she sought help from for her depression understood her problem and was able to give her effective treatment. She was put on an antidepressant, which worked well for her for years. She went off of it for a short period during her physical-therapy education and quickly relapsed into depression again. She now continues to take her antidepressant, but still struggles with depression and is just recovering from a major episode. She says that running for her has been a very powerful antidepressant. She wants to be open about her struggles with depression and how much running has helped her so she can encourage others to also find relief from their depression through exercise, to seek treatment, and to know they are not alone in their depression.

Dr. Onate added a few points about depression that would be of interest to ultrarunners:

- Moderate aerobic exercise for two to three months, four days a week, 30 to 40 minutes a day is sufficient to have an antidepressant effect.

- Modern antidepressants such as SSRI’s (Prozac, Zoloft, Lexapro, Paxil, Celexa, and Luvox), SNRI’s (Pristiq, Cymbalta, Effexor, and Savella), and Buproprion (Wellbutrin) do not significantly affect athletic performance. The older tri-cyclic antidepressants should be avoided in athletes because they can cause cardiac arrythmias among other problems during training and racing.

Brief Summaries of Select Abstracts Presented over the Two Days

[Author’s Note: It is important to remember when reading all of the findings presented in these abstracts that they are preliminary data and have not yet been peer reviewed. The intention with the presentation of these abstracts at the conference was to bring new researchers and up-and-coming research to the conference by having short, 15-minute presentations from studies that have been done but haven’t been published yet. They were presented in the afternoons of Day 1 and Day 2.]

- Valentino TR, et. al. The Influence of Hydration on Thermoregulation during a 161-km Ultramarathon Is dehydration linked to increased core body temperature? Or is it metabolic rate that determines core temperature? Research from 30 WS 100 runners showed that, surprisingly, there was no statistical difference in mean core temperature or body weight throughout the race. However the more weight runners lost, the liklier they were to finish faster. Also surprisingly, the racers who finished more slowly, had a higher core body temperature at the end. (Importantly, slower runners tend to finish during the day when it is warmer.) There was no relationship found between core temperature and body-weight loss.

- Hamilton RT, et al. Hydration Guidelines during Exercise: What Message is the Public Receiving? Only 7.3% of all identified lay and medical/scientific sources said fluid consumption should be based on thirst, 10.4% said salt tabs are not necessary; 2.5% said dehydration was not a cause of muscle cramping; 0% said dehydration is not related to electrolyte loss; 43% acknowledged overhydration is a risk for exercise-associated hyponatremia (EAH). There was significant difference in the information given by medical/scientific websites and lay sources; “They equally continue to promote overhydration.”

- Two posters from one study protocol: Moir HJ et al. Body Mass Changes and Fluid Consumption during an 80.5km Treadmill Time Trial & Christopher CF et al Energy Cost of Running during a Bout of 80.5km Treadmill Running. The body mass among five subjects running 80.5k on a treadmill “as they would run in a race” declined throughout the run, despite ad libitum drinking and eating, and lost on average 4% of their body weight (range of 2 to 5%). Those with highest VO2 max were the fastest to finish; this was a very strong correlation. Vo2 (energy cost of running) increased 21.8% from start to finish. A shift to fatty-acid oxidation (from carbohydrates/glycogen) as main fuel source occurred on average after 32.1k/three hours.

- Hoffman MD. Would You Stop Running if You Knew it was Bad for You? The Ultramarathon Runner Response. Ultrarunners Longitudinal TRAking (ULTRA) Study asked the question “If you were to learn with absolute certainty that ultramarathon running was bad for your health, would you stop participating?” All participants are self-identified ultrarunners and 25.9% answered “yes” while 74.1% said “no.” Those answering “yes” were older on average, more likely to be married, have more children, were running less over the prior year, were more health-oriented, were less achievement-oriented, and less psychologically motivated toward running.

- Høeg TB & Maffetone P. The Development and Initial Assessment of a Novel Heart Rate Training Formula. Dr. Høeg presented Dr. Phillip Maffetone’s original data on a heart-rate-based training program, which, in theory has athletes exercise near and just below their “aerobic threshold.” Of the 223 athletes training at their assigned heart rate for three to six months, 76.2% ran a 5k best time on a certified course at the end of study. In a second study of cases (training at their assigned aerobic heart rate) versus controls (who continued their current training regime), 9.5% of cases developed an injury over the 11-month study period, while 61.9% of the controls developed an injury over the same time frame (p=0.001). The major limitation of this study was the way “aerobic threshold” was defined was vague and is not reproducible.

[Editor’s Note: All images and graphics are courtesy of their respective presenters unless otherwise noted.]