[Editor’s Note: This article was written by Michael Donovan, a New York City-based musician, runner, and soon-to-be law student. His favorite shape is the torus.]

It’s 8 a.m. over Val Rosandra, Italy, and dawn doesn’t break. It seeps — day through the night — exposing a system in the middle of things.

It exposes water in the middle of an endless debate with limestone.

It exposes wind, La Bora, it’s called, in the middle of a stout burst, leaving water for land.

It exposes a city, Trieste, in the middle of waking up.

And it exposes me, a runner, in the middle of a long footrace (see Figure 1) (1): halfway around what locals call the Karst, what Jan Morris calls “The Capital of Nowhere (2),” and what I call Nowhere.

Figure 1. The author Michael Donovan racing the 2025 La Corsa Della Bora in Italy. Photo courtesy of Michael Donovan.

I wasn’t always in the middle of Nowhere. I had to start Somewhere. We all do.

For the water, Somewhere was outer space. They came as a crew of playful molecules whose meteor crash-landed onto a new home here on Earth. For La Bora, Somewhere was the water, a vast oceanic range proved the perfect place to pick up speed. For Trieste, Somewhere was an Illyrian outpost. They figured an endless debate between water and limestone could deter would-be invaders. It did for a while.

And for me, Somewhere was eight hours ago, at midnight, in a village called Sistiana, north of Trieste. It was there that my fellow runners and I found ourselves huddled in a beachside locker room, not-so-patiently awaiting our race director’s parting words.

Some stood still. Others shook.

I don’t remember what I did before the race director shouted, “Something! And something else! Something very important! About safety, probably!”

Who knows? I don’t speak Italian, but I did manage to catch his final “Buona Fortuna!” That was my cue to cross the starting line, out of Somewhere, into … Nowhere.

Giving Enough

Nowhere has been mostly dark up until now.

Eight hours later, it still doesn’t look like much of anything. That’s not to say the landscape’s drab (see Figure 2).

No, I’ve run into a different issue altogether. My eyes have gone on strike.

It’s my fault, really. I failed to satisfy their most basic request: “Eat enough, always (3).” And look, I get it.

The body uses energy. It uses more energy when it runs. Only food, taken steadily, can provide this energy. Hence, when a runner runs a lot, they have to eat a lot. They need a lot of energy. Food is fuel, or whatever. Ultrarunning is an eating competition, another saying goes.

Power to you, eyeballs. Slow down. Resist. You know the drill.

Their efforts remind me of something David Roche wrote for “Trail Runner Magazine.”

We can only pursue a “grown-ass” goal if we give our bodies “enough.” If we expect to do something gnarly — such as trying to finish a 103-kilometer race through the middle of Nowhere, just as I am now — we’d best be prepared to consume the calories required to accomplish such a task. Otherwise, we’d be asking too much of our organs. Only by giving them adequate working conditions can we impel them to accomplish the task at hand: “ripping bones and viscera to shreds” on the path to glory.

“’Enough’ allows for nuance,” Roche concludes. And from nuance: potential.

It makes sense then that I can no longer breathe, move, stand, or see with any kind of alacrity, that it’s even becoming difficult to separate one thing from another. It’s not just my eyes, but all of my organs that are now on strike. They’re holding my nuance hostage, reversing my individuating process until I give them what they need.

I hold out, though, which is why rocks blend into soil, soil bleeds into the grass, grass decays into sheep, and everything congeals into soup, the thought of which makes me even more hungry.

Angry too. Hangry? I’m hangry because I could’ve had actual soup with the woman on the Contovello street corner; or pizza, candy, and Coke to the tune of “99 Luftballoons” with those kids in the Obelisco piano room; or fruits, vegetables, and prosciutto crudo with the man at the Bognoli osmize. I was roaming through a land of plenty, but it wasn’t enough for me (see Figure 3).

Speed

I only wanted speed.

Speed relates time to distance: namely, how much distance can be covered over time. As a racer, it’s my god-given goal to cover this distance in a smaller amount of time than any of my counterparts. I need speed, and I will pay for it, whatever the cost.

Some 120 to 140 grams of carbohydrate per hour, Roche chimes in (4). Sometimes more.

I worry now, taking a note from Paul Virilio (5), that my need for speed contains within it a darkness, and that it’s come to rear its snarling head.

“The invader’s performance resembles that of his athletic counterpart,” Virilio warns. Their goal might seem small, harmless at first: “Olympic champions whose records progressed by hours, then by seconds, then by fractions of seconds.”

But with each incremental shift, the speedfreak gets closer to their limit: “The better they performed (the more rapid they became), the more pitiful were the advances they obtained, until they could only be noticed electronically.”

“One day the champion will disappear into the limits of [their] own record, as is already suggested by the biological manipulation of which [they are] the object, and which resembles the methods of artificial medical survival granted the terminally ill.”

I’ll spare you the lines where I contextualize all this in the current political moment. “I don’t know, said Austerlitz, what all this means (6).”

But I do know that I’m now looking for another way forward (see Figure 4), one that doesn’t require speed as a goal. I have no interest in becoming the “final symbolic manifestation of the moto-power of living bodies (7).” I just want to keep going.

A Desiring Machine

It’s becoming clear to me that if I want to keep going, I won’t be able to do so alone. My own thoughts, while abundant, have shown themselves to do more harm than good.

I look to my running buddy. He’s a 40-something Zen master, more inclined toward consistency than speed. Maybe he can help.

I’d ask him directly, but non so parlare Italiano!

So, I haunt him instead. I’ve been haunting him for a while, in fact: trailing him for hours on end, through the dark of the night, across cities and towns, up mountains, into valleys. I watch his every move. I copy — as all good friends do.

I do this because to be a friend is to be a desiring machine (8). “Desiring machines are binary machines, obeying binary law or set of rules:” 0. He stops. 1. He goes. 0. He eats. 1. He runs. “One machine is always coupled with another.”

As a desiring machine, I don’t have to think. I only have to stop when he stops, go when he goes, eat when he eats, and so on. What’s more: as a desiring machine, I can be a ghost. And it’s not so bad to be a ghost (9). It’s nice not to worry about thoughts or loneliness or anything like that. To instead haunt, forever, consistently.

Such ghostliness might even lead to a more “productive synthesis, the production of production … inherently connective in nature.” It has the potential to connect us with one another and with our ecosystem. There is, however, a catch.

“The first machine is in turn connected to another whose flow it interrupts or partially drains off (10).” This process is necessary and irreversible. Oops. It’s not my fault we’ve amassed a kind of energy that our systems can’t help but dissipate. It’s the law (11)! What else can I do but fulfill my obligation to move, dutifully, from hot to cold?

My solipsistic mood returns.

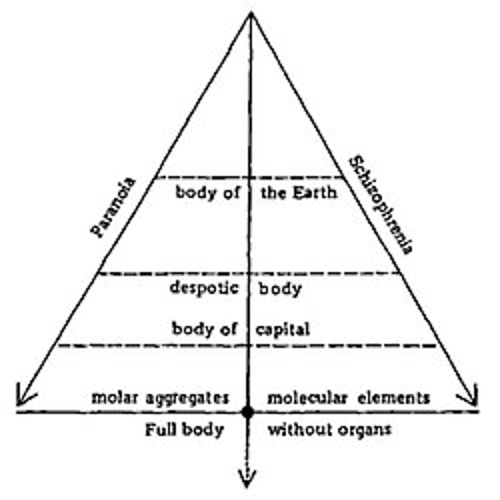

If “every ‘object’ presupposes the continuity of flow,” I conjecture (in my own, highly readable words — see Figure 5) (12), it follows that “each organ-machine interprets the entire world from he perspective of its own flux, from the point of view that energy flows from it: the eye interprets everything — speaking, understanding, shitting, fucking — in terms of seeing.”

Figure 5. The body without organs. Image: “Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia” by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari

Hearing this, La Bora slaps me in the face.

“A connection with another machine is always established, along a transverse path,” they respond (in their own, highly readable words) (13).

The Swerve

I try to keep this in mind as I continue my fade. Where can I go from here? And how?

I wallow, but La Bora smacks me again, this time sending me spiraling toward “ontogenesis” but “in reverse (14).” This slap shatters my machinic mess of a self into a trillion tiny pieces. I scatter. I compress. I get smaller and smaller and smaller and smaller until I fold into myself and meet the swerve.

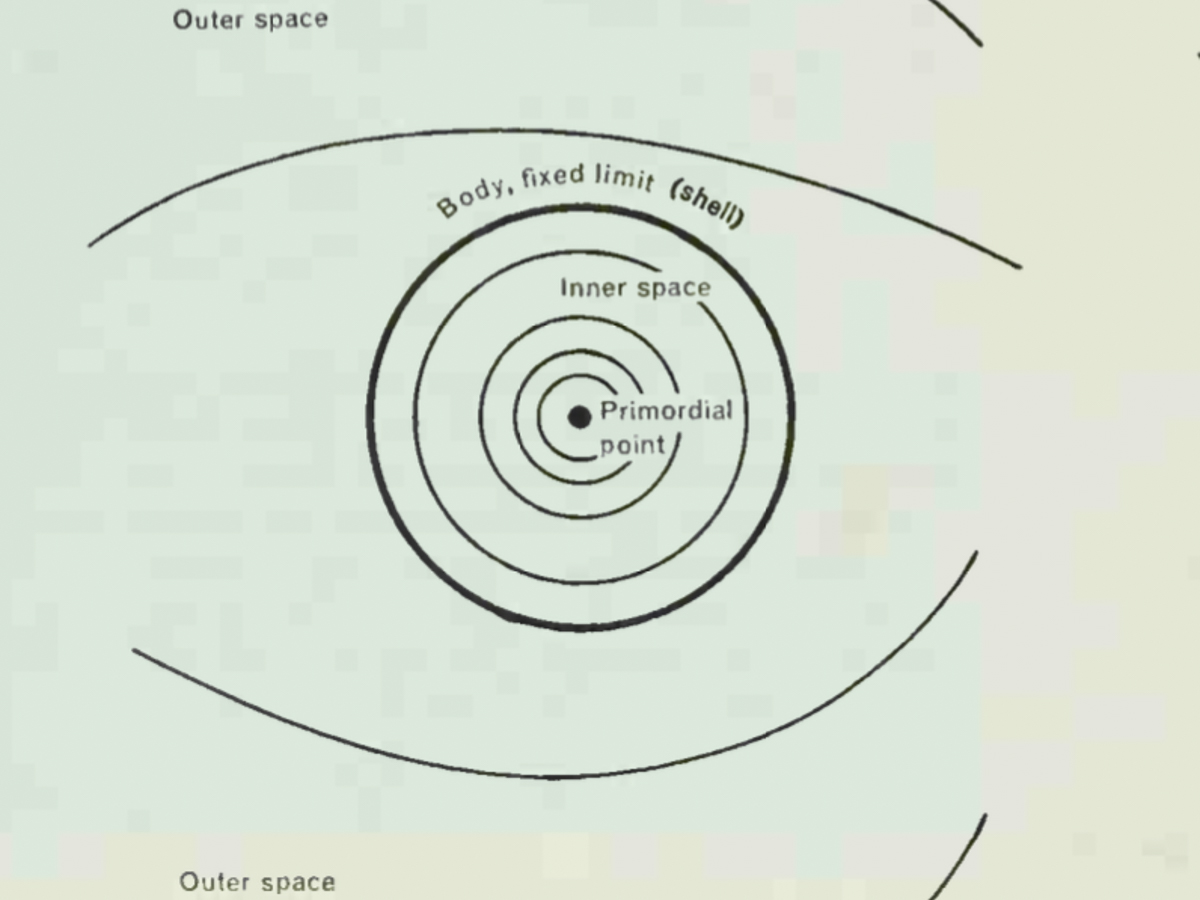

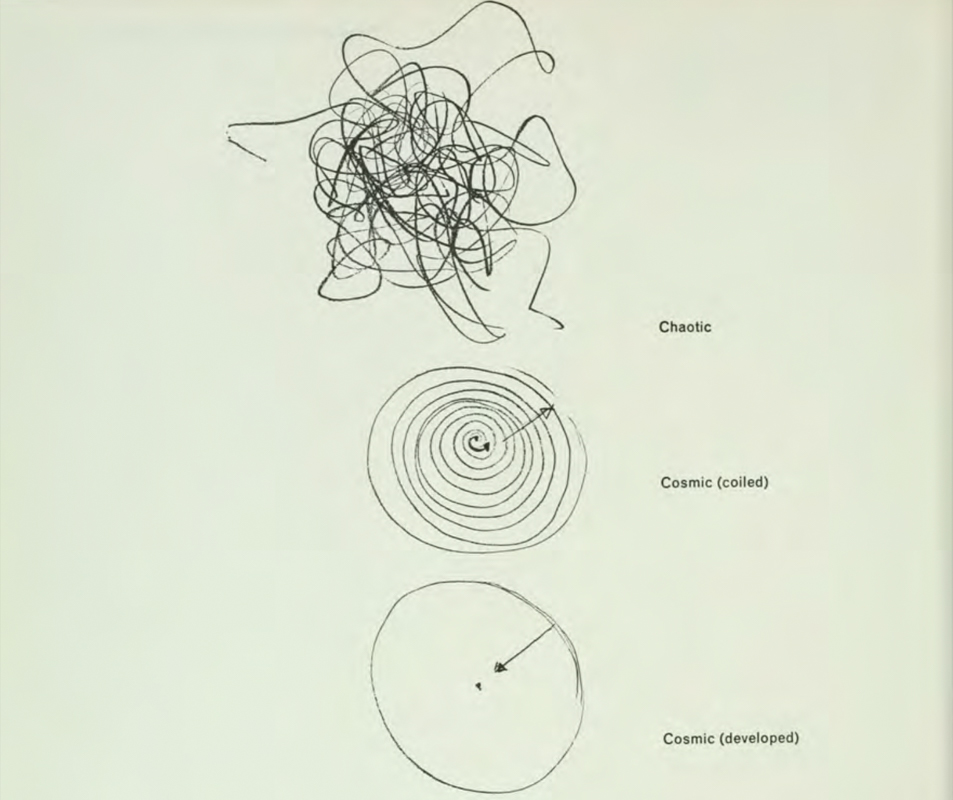

The swerve? It was Lucretius who gave us the swerve (15), though he called it clinamen. The concept also appeared in Karl Marx (16), later in Virginia Woolf (17), and it has since found a new life in the philosophy of Thomas Nail (18). But I like to think of the swerve through the work of Paul Klee, who implied that it all starts with a point (see Figure 6) (19).

This point, like the dawn sky, “can only be grey.”

Once established, a “point in chaos” (see Figure 7) can imbue its inherent discomfort (infinite folding) with the “concentric character of the primordial.” It can instantiate “the cosmogenetic moment!” Pretty neat, right?

I think so. But there is, of course, another catch.

Any instance of “cosmogenesis” must necessarily be accompanied by a “potential energy,” which attracts all generated matter back toward the initial point (20). What a drag!

This opposition between centripetal and centrifugal cosmogenetic forces, taken together, represents what many big thinkers have called difference. And, somewhat ironically, these thinkers have developed two opposing ways to think about difference as such.

Hegelian Difference

The first is Hegelian (see Figure 8): difference is always from something, i.e., lack (21).

I don’t like this because it requires lack — it means I’ll always lack something — and that I’ll inevitably run into the problem of not having enough, no matter what I do.

Figure 8. Nervous Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Image: Lazarus Gottlieb Sichling/After Friedrich Julius Ludwig Sebbers

If I had enough, for Hegel, then I wouldn’t really have anything. My life force wouldn’t even exist. He thinks there needs to be something more. Something different. Something we want but can’t have. Something to keep us going.

Thinking about the concept of difference in this way also has a nasty tendency toward locking its practitioners in a pattern wherein they become “infinite receptacles for consumption (22).” Have you ever been an “infinite receptacle of consumption?”

I have. It sucks.

Deleuzian Difference

That’s why I’d much rather think Deleuzian difference: “difference” that is “determination as such” (see Figure 9) (23).

This kind of difference — which generates our minds through matter along with everything else in one fluid and continuous movement — makes no attempt whatsoever to pit any kind of “determination” against another. Instead, it allows all determinations to work together within a single “harmonious organism,” playfully painting history, which it defines as little more than “a point between dimensions (24)” onto an indeterminate future.

I take comfort in this kind of difference because it implies I already have enough. Sure, I still can consume. I might even have to consume, especially if I’m driven by desire, as it were. But such consumption — and the desire for it — wouldn’t be a response to lack. It would be a thing in and of itself. It would be fundamental. It would be a point: the swerve.

“To this occurrence corresponds the idea of a sort of beginning (25).”

New lines extend outward: I can go about walking, jumping, running, “moving freely” (see Figure 10). I can embrace the notion that “everything (the world) is of a dynamic nature; static problems make their appearance only at certain parts of the universe (26).”

I can dive into the fleeting nature of my “faltering existence on the outer crust of the Earth” because I know that “strictly speaking, everything has potential energy directed towards the centre of the Earth (27).” And that this energy could be difference. And that this difference could be life.

To think of this kind of difference, I need only turn myself away from a “vision of nature that would be universal, deterministic, and objective inasmuch as it contains no reference to the observer, complete inasmuch as it attains a level of description that escapes the clutches of time (28)” and turn myself toward a vision of nature as play.

Middle of Things

Frame adjusted accordingly, I conclude that I’m not actually running from anything.

I’m different (29), and I run because it puts me right in the middle of things. It puts me in an indeterminate place where the tension between past and present, hot and cold, inward and outward, conducts a beautiful and self-organized symphony.

In this place, “time is the thing (30)” — but don’t be a “Tár” — and time moves everything to the meter of its unsteady beat.

The Karst

I stand motionless for a moment, relieved.

I also wonder what this new difference might have to say about Jan Morris’s grounding assumption: “Trieste cannot escape the Karst (31).”

It’s true their “hills of queerness” — “so obsessed with stone” — have always been able to absorb the rise and fall of empires, the creation and destruction of borders, the evisceration of life into their deep temporal chasms. “Time is the thing.”

But is it also true that the Karst cannot escape Trieste?

Perhaps I could argue that the Karst actually wanted their stones to become houses, their hills to be planted with food, and their caves to be filled with cheese. But, on that same token, I’m not sure I could say the same about their stones becoming trenches, their hills becoming hunting grounds, and their caves becoming filled with lifeless bones.

Only if the Karst cannot escape Trieste would this latter line of questioning make any sense. It would also point us toward the realization that Trieste and the Karst are more than just an inseparable pair. They are one and the same: ecological equivalents, interdependent to a fault. Under this equivalency, both darkness and light (their perpetual opposition, the grey between them) belong not just to the Karst or Trieste but to both simultaneously. This would also mean that all this darkness and light and everything in between belong to me as well. I’ve got no say in the matter. I cannot escape the Karst.

La Bora blows again, and I sing to myself:

“I’ll never know which way to flow

Set a course that I don’t know

I’ll never know which way to flow

Set a course that I don’t know

The wind’s blowing on my face (33).”

It comforts me as I watch the sunrise (34), give the sheep my best, and allow myself to be moved.

For eight more hours, I’ll go down mountains, between trees, through more towns and cities, up onto cliffsides, back down them again, through the trenches even, always moving, just enough, and happily so (see Figure 11).

Notes/References

- La Corsa Della Bora – S1 Trail 103k.

- Morris, J. (2006) “Trieste and the meaning of nowhere.” CNIB.

- Roche, D. (2023) “The Science of Low Energy Availability and Performance.” Trail Runner Magazine.

- He needs to chill.

- Virilio, P. (1977) “Speed and Politics: An Essay on Dromology”

- Sebald, W.G. (2001) “Austerlitz.” Hanser.

- He also needs to chill.

- Deleuze, G., Guattari, F. (1983) “Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia.” University of Minnesota Press.

- Rosenstock, J. (2016) “To Be a Ghost … ”

- D & G

- Clausius, R. Second Law of Thermodynamics.

- D & G

- D & G

- Simondon, G. (1882) “The Genesis of the Individual”

- Lucretius. “On the Nature of Things.”

- Marx, K. (1841) “The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature.”

- Woolf, V. (1931) “The Waves.” Hogarth Press.

- Nail, T. (2024) “The Philosophy of Movement.” University of Minnesota Press.

- Klee. P. (1964) Notebooks. Benno Schwab.

- “Notebooks”

- Colebrook, C. (2002) “Understanding Deleuze.” Routledge.

- Virilio, again.

- Deleuze, G. (1995) “Difference and Repetition.” Columbia University Press.

- Paul Klee, going hard in the Notebooks.

- Klee.

- Klee!

- Klee! Klee! Klee! Klee!

- Stengers, I., Prigogine, I. (1984) “Order Out of Chaos: Man’s New Dialogue with Nature.” Bantam.

- Derogatory

- Field. T. (2022) “Tár.” Focus Features.

- Morris, again

- Cheese caves!

- Teenage Fanclub. (1990) “Everything Flows.” Paperhouse.

- Big Star. (1972) “Watch the Sunrise.” Ardent Records.