[Editor’s Note: We respectfully inform readers who are sensitive to the topic of self-harm that this article contains descriptions of suicide ideation and violent behavior.]

It’s a Friday in late October, and Nickademus and Jade de la Rosa are not doing what they love, which would be running trails and bagging peaks together, or hanging out in their Bellingham, Washington, home with their gaggle of two dogs, several guinea pigs, and two rabbits.

Rather, as chronicled through Nick’s Instagram story, they’re back in the hospital. Jade does a little dance with swaying hips to boost their spirits. Then the camera pivots to Nick in a hospital bed. He’s groaning and half-hiding under the sheets, his eyes and his curly dark hair looking more wild than usual.

Nick then posts a message in text: “I’m fine. This is just how we like to spend Friday mornings sometimes. #blessed #idrathernotberunning”

Those hashtags were sarcastic, Jade confirms a few days later, as she speaks about the physical and mental health struggles of her husband, who until two years ago was in the top tier of ultrarunning. “Nick found out he had accidentally gone off one of his medications,” Jade says, explaining the social-media post. “We spent four hours in the emergency room and were a bit delirious. … We’re both pretty open and don’t feel much embarrassment about being ourselves.”

Nickademus and Jade de la Rosa right after getting engaged in July of 2016. All photos courtesy of Nickademus and Jade de la Rosa.

Over the past two years, the couple has shared numerous posts showing Nick in a hospital and Jade supporting him as he copes with both a cardiac condition requiring open-heart surgery and a mental illness so serious that he’s been on suicide watch.

But other posts show them smiling on summits in the midst of runs, or celebrating as Jade earned third-place finishes in both the 2019 Santa Barbara Nine Trails 35 Mile and San Diego 100 Mile. They look as loving and strong as they did before the illnesses that have sidelined Nick.

Many have been concerned about them and wondering, what have they been through, is Nick on the mend, and how is Jade coping with it all?

Nick and Jade agreed to share their story. They speak candidly with a desire to raise awareness about mental illness and to destigmatize therapy. “Running can be a part of healing, but for many if not most cases, it can’t take the place of actual therapy,” says Nick, because running—as in his case, he believes—can be “abused in an unhealthy manner” and can be symptomatic of underlying issues that cause psychological pain.

But first, some context: Nickademus Hollon—Nick’s name before he and Jade married and chose de la Rosa (Nick’s great-grandfather’s last name) as their shared surname—is someone whom many in the sport began following a decade ago, as the kid from San Diego, California, began racking up impressive ultrarunning credentials before reaching the legal drinking age.

At 19, he became the youngest finisher ever of the Badwater 135 Mile, which runs through the extremely hot and arid Death Valley National Park in California. At 20, he ran a 21:40 at the Western States 100, followed by another Badwater, and then the self-supported Plain 100 Mile. At 21, he finished the snowy Arrowhead 135 Mile in northern Minnesota and made his first of three attempts at the infamous Barkley Marathons, an orienteering-style race more than 100 miles long in Tennessee.

In 2013 at age 22, he won and became the 13th finisher of Barkley, a rarified group that today includes only 15 men. Later that year, he also finished two more 100 milers and the 205-mile Tors des Géants in Italy.

The next four years brought a second place at the 2014 Tors des Géants, second place at the 2014 105-mile Ronda dels Cims in Andorra, a win of the 2014 Devil’s Double in Nicaragua that combines finishing both the Fuego y Agua Survival Run and 100k over four days, third at the 2015 HURT 100 Mile, course-record wins at the 2015 Fat Dog 120 Mile and 2016 Crewel Jewel 100 Mile, and a sixth place at the 195-mile Dragon’s Back Race in Wales in 2017.

Skip ahead two years, to July 12, 2019, and Nick shocks many with an Instagram post.

It’s not the picture that floors his followers. The photo shows Nick and Jade looking as in love as ever. Shoulder-length dark curly hair, a mustache, and a goatee frame Nick’s broad-smiling face. In the background, Jade also smiles wide as she looks over his shoulder, head tilted, embracing him.

It’s the caption, which not only surprises but also puts together many of the complex puzzle pieces of Nick’s health problems: “Hey world, so this is just a short announcement and I guess an awareness post so none of you are shocked by the future things I might start sharing here on social media. I’m on high risk suicide watch. And have been for some time now. I’ve got a cocktail diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, complex post-traumatic stress disorder, sporadic depression, and crippling worthlessness. For most of my life, ultrarunning helped me keep all of this at bay. Then in 2018, heart surgery sidelined me. And a mental illness that I’d unknowingly been running from my entire life started catching up to me. … Despite the risk, I’m stable. I’ve got the help and level of care I need. I’ve got my safety plan and an excellent team of therapists working with me. But most of all, I’ve got Jade. The most caring, dedicated and supportive person I could have ever married. Jade, I can’t pretend to know how impossibly hard all of this has been for you. I love you more than you could ever know.”

Not even 30 yet, Nickademus and Jade have been through more extreme highs and lows as newlyweds than some couples experience during a lifetime together. Ultrarunning—the backdrop to their relationship and their shared passion—has alternately strengthened and complicated their health and happiness.

Ultrarunning as a “Socially Acceptable Form of Self-Harm”?

Nick began to identify with being a runner in sixth grade. His parents—who, according to Nick, had him at the young ages of 20 and 22—had just divorced, and he and his younger sister moved with his mother to San Diego.

“I was an angry kid” because of the divorce and move, which separated him from his father and caused him to change schools repeatedly, Nick recalls. “I struggled to find solid ground or identity while my mom worked her butt off at odd jobs, while we lived in my uncle’s spare bedroom. … I began to feel at my core that I didn’t matter, and that anything I did or felt would be a burden to my mom.”

In essence, Nick says, “While my parents provided the necessities of food, shelter, and education, I [didn’t receive] the message that I was lovable for who I am.”

In a brand-new school, he had to run a timed mile in physical-education class. “I remember getting myself really pissed off and running that mile stupid hard. And I won it. The validation I got from kids afterward, the ‘whoa you’re so fast, you’re so cool,’ gave me the feeling that this is something I could get recognition for.”

Running gave both his mom and himself an outlet during tough times, Nick says. “I watched my mom come home stressed, go for a run, and come back looking much happier. Wanting to bond with my mom, I thought maybe I could get into that, and maybe I could get attention from her.”

Nick ran his first marathon when he was 15, a couple of years after his mother ran her first. He finished the 2005 San Diego Rock ‘n’ Roll Marathon in 3:29. Nick says he saw being young and running a marathon “as a way to shine brightly” amongst peers. He adds, “If you asked me a year ago” why he started running marathons and longer, “I would still give you the happy story that I followed in my mother’s footsteps, so this is recent stuff I’ve unpacked in therapy … that what got validated as valuable in my life was when I finished an ultra or won something, and there were media accolades, and then my mom supported me.”

At 17, during his senior year in high school, he ran 3,000 miles to raise $10,000 for the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society after a friend was diagnosed with cancer. At the end of the school year, he ran his first 100 miler by completing 400 laps on the high-school track.

By the time he went to college at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, Arizona, where he majored in Anthropology and Spanish, Nick says he had internalized a voice telling him that he would not gain approval unless he stood out as an extreme runner. “That’s why cross country and track never interested me; I needed to enter weird things like 100 milers, to be the youngest.”

Nick also began to idolize ultrarunners Dean Karnazes and David Goggins, both of whom competed in the Badwater 135 Mile in the mid-2000s. Imitating the deep, macho-sounding voice of Goggins, the former Navy SEAL who’s revered by many ultrarunners, Nick says, “You want bad ass? You gotta’ do 135 miles across the desert!” The idea gripped him as he entered college, and he told himself, “I probably don’t have a chance of winning it, but I can be the youngest person to do it”—and so he did. Thus began a period in young adulthood of seeking ever-more-challenging events.

“He was so mentally tough as an athlete,” recalls Gary Cantrell, aka Laz, the race director of the Barkley Marathons who watched Nick come close to finishing his event in 2011 and 2012, and ultimately win it in 2013. “He let everything shed off him, like water off a duck’s back; he was never agitated, never upset. He was disappointed the times [at Barkley] he didn’t make it but resolved, ‘I have to get better.’”

Cantrell credits Nick’s success at Barkley in part to his focus and his ability to find his way through the disorienting landscape by remembering landmarks. “He’s a really good woodsman and knew exactly where he was when he was out there. … He was all business. It’s a very tight time limit, so [in between the course loops] we might exchange a sentence or two, and then he was off to get his job done.”

Nick credits his success more to a detrimental psychological drive. “Barkley, Badwater, and these more extreme races were my versions of self-harm,” he says. “They were well received by my society. Society and my mom made me feel worthy for completing them, so I continued finding harder and harder events.”

Asked to elaborate what he means by ultras being a version of “self-harm,” Nick points to racing the 2013 Tors des Géants, where his knee became extremely painful mid-race. In an interview with Ultrarunnerpodcast from 2014, Nick had previously described a moment during that race when “my knee was the size of a frickin’ softball, and I came to the aid station thinking, ‘Oh my god, my race is done.’ My mom, who was part of my crew, was like, ‘No it’s not, you put some frickin’ ice on it, sit down and shut up for 15 minutes, and then get back on the trail.’”

Now he looks back and adds, “I’d be 15 minutes down the trail and my inner voice would be like, ‘C’mon, you worthless piece of shit, you gotta’ get up this thing, you deserve this pain.’ … In that sense it was a very socially acceptable form of self-harm.”

Nick no longer lives near his parents, and he says his relationship with his mother is “distant” and his relationship with his father is “strained.” Contacted for this article, Nick’s mother declined to comment on the relationship with her son.

Falling in Love “Adventure to Adventure”

Enter Jade, a source of joy in Nick’s young adulthood. They met after Nick graduated from college and moved back to live with his mother and stepfather near San Diego, and they bonded through adventure, dancing, humor, and a mutual love of animals.

Unlike Nickademus, Jade Belzberg (her maiden name) never thought of herself as a runner until Nick introduced her to the sport. Growing up in British Columbia, “I signed up for track and field in Grade Three. … In the 800-meter race, I came dead last. That solidified for me that I was not an athlete, and I carried that until I met Nick.”

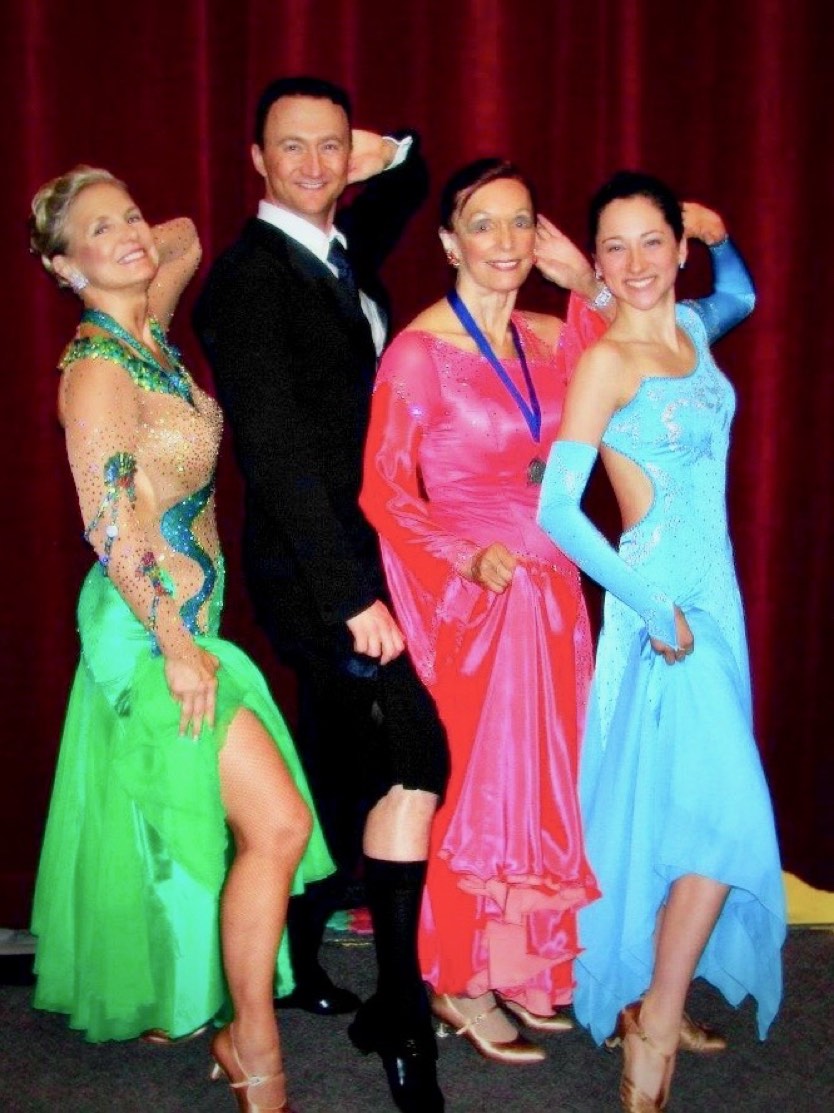

Instead of traditional sports, Jade took up ballroom dancing with her brother—a hobby she rekindled with lessons in 2018 and a competition earlier this year. “My mom had always pushed us to try ballroom dancing because my grandmother and her brother were champion dancers. I [enjoyed that] it could be practiced in any clothing and changed dramatically from dance to dance.”

The couple connected online through Match.com and had their first date in October of 2012 at a Mexican restaurant in Old Town San Diego. Jade had recently relocated after transferring to the University of San Diego, where she earned a degree in 2013 majoring in English and Creative Writing. She’d go on to earn a Master of Fine Arts in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts five years later.

“I felt like we had a pretty good connection right off the bat. I loved how engaged our conversations were,” Nick recalls. It took time for the pair to develop a shared romantic interest, but, says Nick, “a month later, Jade asked me out to dinner. From then on, beginning with a random peak in San Diego and my falling-apart Jeep, it was adventure to adventure.”

While their relationship was still new, Nick hit Jade with a monumental adventure in March of 2013: the Barkley Marathons, where Jade and Nick’s parents crewed him. “That was my first experience being at an ultra, and Barkley is about as eccentric as you can get. The whole thing had me out of my comfort zone,” she says.

Nick and Jade at the 2013 Barkley Marathons. Jade was part of Nick’s crew, while Nick had just become the race’s 13th-ever finisher when this photo was taken.

A year later, at the 2014 Tors des Géants, Jade had grown accustomed to crewing Nick, though not without mishaps. When she showed up on a mountainside to meet Nick with 25 miles left in the 205-mile odyssey, he was craving candy. He popped into the aid station with the third- and fourth-place runners not far behind and asked Jade for his Sour Patch Kids and Skittles.

“I lost your bag, Nick, but I’ve got these hot-dog buns,” she told him. They both bust up laughing now as they recall the absurdity of him finishing in second place while stuffing himself with processed white buns.

Nick’s first gift to Jade was a pair of trail-running shoes and entry to a local race. Jade says of trail running, “I was thrown into it, and I loved it right away.” As a child, her care for animals and the outdoors led her to get involved with youth-oriented environmental causes, and “finding trail running [as an adult] was a way of connecting different parts of me—exploring, birding, gardening, environmentalism—with a physical side I hadn’t experienced before.”

Her first ultra was the 2014 Born to Run 50k. She finished with an impressive time of 4:39. “Then it was a matter of me finding confidence. … It took me a long time to call myself an ultrarunner because Nick’s presence in the sport was so big that I couldn’t possibly match up.”

By 2016, she graduated to 100 milers, running the Zion 100 Mile and Cascade Crest 100 Mile. Having not run competitively earlier in life, Jade says, “part of my love for the sport comes from a place of curiosity and growth: What can I do?”

Says ultrarunner and race director Paul Jesse, a friend who paced Jade at the San Diego 100 Mile this year, “Jade is a beast! One of the things that stood out was how fast she can powerhike. … She’s an incredibly smart and strong runner who’s good at adjusting to the constant issues that come up during a 100 miler.”

On September 23, 2017, Nick and Jade tied the knot at a wedding ceremony near San Diego, then honeymooned in Hawaii, where they not only ran as many trails as they could, but also met a stray dog and adopted him.

In early 2018, they moved to Bellingham—a place they felt drawn to because Jade had attended college there. “We were looking for a smaller community and a new area to explore, and looking for some independence after living so close to our families,” says Jade. Later that year, the couple set an unsupported mixed-gender fastest known time on the West Coast Trail, about 50 miles along the Pacific coast of Vancouver Island in British Columbia, in 13 hours and 18 minutes.

But their honeymoon was short-lived, because a severe heart condition, followed by a serious mental-health diagnosis, caught up to Nick.

“A Walking Time Bomb”

After Nick won the 2013 Barkley Marathons in 57 hours and 39 minutes, he traveled back to San Diego to race again just three days later at the 22-mile Rabbit Peak. Asked why he’d immediately race after the brutal Barkley, he says the shorter race was part of a series that he stood to win, so he wanted to gut it out.

During that race, he experienced significant breathing troubles and an irregular heart rate, so he sought medical help.

An echocardiogram revealed Nick was born with a bicuspid aortic valve, meaning that his valve had two flaps controlling the one-way blood flow instead of the normal three. This irregularity, occurring in the valve between the left ventricle and the aorta (the main blood vessel that carries oxygen-rich blood to the body), can lead to the valve malfunctioning and the heart working harder to pump blood; over time, it can be risk factor for developing serious cardiac problems, including an aneurysm. The doctor told Nick he should monitor his symptoms, but he was not at an immediate risk.

“I went without health insurance for a few years, enjoyed the best years of my ultrarunning career, and didn’t ever think about it,” Nick says. He attributes this cavalier attitude toward his health to an upbringing that did not prioritize going to the doctor or dentist “partly because of finances and partly because of ignorance.”

During 2016, Nick launched his coaching business—called Lucky 13, after his Barkley finish—and grew it into a success. After Jade and Nick became engaged and married, in late 2017, she urged him to get health insurance and have his heart checked.

“The cardiologist was semi-alarmed when he saw a 5.1-centimeter ascending aortic aneurysm,” which is an abnormal bulge in a section of the aorta. If untreated, it can burst and be life-threatening. “I proceeded to run 42 miles with Jade in the Grand Canyon the following weekend,” Nick says.

Nick’s action begs the question, why do an ultra-distance run right after such a diagnosis? Nick says he wrongly viewed toughing out an ultra in the face of a health warning as “a badge of honor,” an attitude cultivated from seeing other respected endurance athletes tough out their injuries. And, he explains, “I didn’t tell Jade about the conversation I had with my cardiologist, and she didn’t find out about the seriousness of it, until we met with another cardiologist a week after the run.”

At that follow-up appointment, the day after Christmas of 2017, a surgeon told Nick that he was “a walking time bomb.”

Nick had the surgery to repair the aortic aneurysm in January of 2018. The open-heart surgery replaced the dilated portion of his aorta with a tube and was successful. However, he was under-prescribed an anti-inflammatory used to treat swelling in his pericardium, the thin tissue layers surrounding the heart, a side effect of surgery. As a result, he developed recurrent pericarditis, which causes chest pain due to that inflammation. This sent Nick back to the emergency room four times in the four months following his surgery.

Finally, in June of 2018, he got on the right anti-inflammatory dose and was able to return to recreational running and compete in a couple of 25k to marathon events. Then, in January of 2019, Nick and Jade traveled to Hawaii to run the HURT 100 Mile together.

Nick previously finished HURT four times, and based on his training in late 2018, he felt optimistic he could handle a 100-mile race again. At mile 23, however, he experienced blurry vision and a weak pulse, so he dropped out and headed to a hospital. Jade then dropped at mile 68, her first DNF. “I started feeling selfish to be running while my husband was going through medical issues,” she says.

Off and on since his heart surgery, including at HURT, Nick says he has experienced “severe bonks that felt like dizziness, fainting, nausea, my left arm going completely numb, tingling in my arms, and an inability to get my heart rate up.”

This past June, magnetic resonance imaging and an echocardiogram diagnosed “athlete’s heart” or increased cardiac mass from high-intensity training. Given Nick’s medical history, his cardiologist recommended that he severely limit his exercise for three or so months this fall and winter. The hope is that intentional deconditioning will reduce the size of his enlarged ventricles, resolve his symptoms, and allow him to run regularly again in the new year.

Nick has been following his doctor’s advice—to a point. “Since heart surgery, we’ve been living in a gray area about my recovery. There aren’t many people my age or fitness level who have had this surgery, so getting advice from my surgeon and cardiologist about returning to the sport are educated guesses.”

Consequently, Nick admits to “cheating” and running once or twice a week even during these months when he’s supposed to limit exercise. On the morning of our interview in early November, he and Jade ran 20 slow miles in the mountains, their running interspersed with hiking.

Pressed to explain why he would run instead of rest, Nick says the situation isn’t simple. For one thing, a recent stress test on his heart, conducted on November 5, showed his blood pressure, lungs, and cardiac output to be normal, suggesting his risk level has lowered. Also, “my own research on athlete’s heart and cardiomyopathy, along with conversations with my cardiologist, made me certain that if we focused on reducing external stress, inflammation, and [overall] activity level, then one to two runs per week would be psychologically beneficial as we work through difficult mental-health issues.”

Running—which he says previously contributed to self-harm—now feels like a source of healing. “It brings me immense joy and satisfaction now. … It’s is a big comfort and coping mechanism, and catch-up time, for Jade and I.”

“I Don’t Want to Exist Anymore”: Nick’s Mental-Health Crisis

Sitting side by side at the kitchen table of their Bellingham home, being interviewed via a video call, both open up about Nick’s mental-health issues.

Starting in 2017, when knee pain limited his ability to train and race, through his hospitalizations in 2018, Nick’s ability to moderate his emotions became less stable. He and Jade describe feeling stressed as they adapted to being newlyweds and moving to a new home, while also facing the unexpected need for cardiac surgery.

How did they cope? “Hamilton,” Nick deadpans, and Jade laughs and adds, “We did listen to a lot of Hamilton” and saw the musical the week before his heart surgery.

They turn serious when asked to describe their most painful episodes, beginning in June of 2018.

One day, Nick and Jade were running on Thurston Mountain near Chilliwack, British Columbia, in worsening weather conditions. Nick says he became fixated on reaching the summit in spite of freezing temperatures and cold rain, while Jade expressed trepidation about continuing but also didn’t want to let him down by stopping. Their conversation devolved into a terrible argument that Nick admits climaxed in him forcefully grabbing her, throwing her down into the snow, and screaming at her.

“Realizing what I’d done,” Nick relates, “and disgusted with myself, I wandered over to a cliff and was looking for the best spot to jump. Jade was shaken up but didn’t realize what I was looking at. [Because of the weather] we headed back down, having never summited. I vacillated between sobbing, screaming, and maniacal laughter. … That’s when we realized the seriousness of my condition.”

Jade recalls, “I felt extremely scared but didn’t want to react during the event and provoke more anger. I felt like I was looking at a Nick I didn’t know. … It was clear to both of us that something was very, very wrong and he needed help.”

Nick sought a psychological evaluation and received a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, a mental-health illness characterized by extreme and impulsive emotional reactions, unstable relationships, fear of abandonment, feelings of worthlessness, and self-harming behavior.

Getting a diagnosis and medication, plus entering Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, “has helped a ton,” Nick says. The specialized therapy gives tools to handle a suicidal impulse, he says; for example, he’s learned to take a freezing-cold shower “and sit in it as long as I can tolerate. The idea is that it’s so frickin’ cold, you can’t think of anything except ‘damn this shower is cold,’ so it snaps you out of your train of thought.”

Asked to describe these dark, impulsive moments, Nick talks quickly, stuttering slightly, sometimes putting both palms to his forehead while closing his eyes. “Man, it’s such a dark—I mean, the thought is basically, I don’t want to exist anymore because I’m causing others so much pain and I’m a burden. By existing on this planet, I’m just hurting Jade more. … It’ll come on very impulsively and be very strong for 15 to 30 minutes; the message is: Kill yourself, you’re not worth anything, you’re letting everybody down.”

As he speaks Jade listens calmly, sometimes reaching out to touch his arm. What have these moments been like for her?

Initially, Jade says, she was “completely scared” when Nick threatened to take his life, and she struggled with whether to call the police. “My individual therapist has saved me through all this because I now have some actionable steps to take in these moments. Prior to working with her, I felt helpless.” Her therapist also advised her “that I can’t prevent Nick from committing suicide. That’s too huge of a burden for anyone to carry, so my reaction to his suicidal behavior has been perhaps calmer than some might expect. … It sometimes has felt very lonely being on the inside of all this, because it’s hard for me to explain to other people what it’s like being the caregiver.”

Coping with Nick’s mental and physical illnesses “has nearly torn our marriage apart,” Nick says, “but with Jade’s unconditional love and the help of therapists, I’ve been able to sift through all this and slowly reformulate a much healthier relationship” to his self-identity and sport.

Continuing to HURT and Heal

Currently, Jade is training to race the HURT 100 Mile in Hawaii this coming January, which she says feels relatively celebratory, given what they’ve been through. “It’s a privilege to be running ultras now, because it’s been so difficult to start and finish them amidst all this therapy and relationship work.”

Nick is preparing to crew her there, but not race. “I want to continue seeing Jade get better and do whatever I can to help her” as an athlete, says Nick.

Nick has no idea whether he’ll return to running 100 milers next year, if his heart size shrinks as intended from his deconditioning phase of treatment, and if his cardiac condition allows him to train at a higher intensity and with consistency. He misses racing and the ultrarunning community, but he doesn’t want to stoke the self-critical inner voice that was inherent in his earlier success. He muses, “If I’m not trying to win something, then maybe I’m just gonna’ go run 100 miles through a national park because it’s pretty.”

Asked about their longer-term plans heading into their thirties, Nick says, “Ten more years, 10 more animals,” only half joking.

Are the animals substituting for something human? Nick laughs, “Poking around the baby question! I don’t want to have a kid while I’m still actively dealing with psychological issues.”

Jade adds, “I think kids are a real possibility, but we’re looking at least at five years.”

Nick plans to continue coaching, and he expresses an interest in sports psychology. Jade, who works as a freelance writer, is at work on a historical-fiction novel.

Jade finishing her Master of Fine Arts by reading a chapter of her novel manuscript in July of 2018.

For now, Nick says he is focusing on wellness and what he can control. “In many ways my health is better. I get eight-plus hours of sleep, I’ve cleaned up my diet and am mostly plant-based now, I’ve reduced stress, I go to therapy and meditation, and I’ve recently taken up tai chi.”

While Jade aspires to compete more seriously in ultras, and running brings them joy together, ultrarunning now feels secondary to their priorities of nurturing mental and physical health, along with strengthening their relationship. They realize they can’t let ultrarunning define them. Case in point: In September, they traveled to race the Olympic Mountains 50k in Washington, had a nice time car camping, and then decided not to start on race morning.

“Normally [the race] would be the weekend’s centerpiece,” Jade recalls. “We were so relieved to have a break from therapy. We spent time shopping, slept, and then woke up and asked each other, ‘Are you in the mood for this?’” They weren’t, realizing it’s okay to do something else.

Asked what he hopes people will take away from the experiences that he and Jade have shared, Nick says, “I want people to hug your loved one and let them know you love them no matter what. Like Mister Rogers would say, ‘I love you for being just who you are.’ That can’t be overstated.”