Summary

Skeletal muscle breakdown is expected following an ultramarathon, and very rarely leads to clinically significant exertional rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis can cause kidney failure or heart stop in the worst cases. Signs of clinically significant rhabdomyolysis during or after a race include generalized muscle pain or weakness out of proportion to the effort, cola-colored urine, or the inability to urinate 12 to 24 hours post-race. Clinically significant rhabdomyolysis can occur alongside low blood-sodium levels due to overhydration, adding complexity to the health emergency. Specific training and proper hydration are among the chief ways of avoiding this illness.

Introduction

It was his third time running the race, and this time he was easily on pace for a course record. It was a mountainous 100 miler that no one finishes in under 24 hours, but at mile 70, it still looked like he might. He felt incredible. As he crested yet another peak with a stunning vista, it dawned on him that this might be the race of his life. JH is a runner I came to know because he was hospitalized for rhabdomyolysis. He wishes to remain anonymous for the purposes of this article, so some of the details of his story have been changed to respect this wish. A mutual friend put is in touch when he wanted medical advice.

It was somewhere around mile 80 of the race that things started to go wrong–very wrong. There was an extremely steep downhill at this point and he kept falling backward, which was strange for him. But then, when the trail flattened out, it became clear that what he was experiencing was not within the realm of normal–even for an ultrarunner. He fell hundreds of times. His pacer, also a very accomplished runner, was worried he might get a head injury or fall off a cliff. JH kept going, though he had to walk most of the last five miles; his legs simply did not have the coordination required to run. His pacer suggested he drink or eat, but drinking sounded terrible. He had been forcing down energy drink and salt tabs, but, if anything, they made him feel worse. With five miles to go, he began to vomit.

His wobbly hobble across the finish line was met with huge cheers–he had won and set a new course record, though missed coming under 24 hours. He smiled and hugged his wife and thanked the race director, but he could not keep standing and went directly to his hotel room. Another 24 hours later, he had still not urinated and the nausea continued. Anytime his wife tried to get him to drink anything, he would start to vomit.

When I asked JH to tell me his story, I expected the classic story of rhabdomyolysis: muscle pain and cola-colored urine. But what he described reminded me much more of exercise-associated hyponatremia (dangerously low sodium levels in the bloodstream), with his inability to control his legs, nausea, and aversion to water.

What is Rhabdomyolysis?

Let’s back up. What is rhabdomyolysis and how would we know if this was JH’s problem?

The word “rhabdomyolysis” is Greek for “striated (skeletal) muscle breakdown.” Skeletal muscle breakdown is abnormal in a resting person, but normal following any sort of exercise that is longer or more intense than a person is accustomed to. Thus, a certain degree of skeletal muscle breakdown is expected from an ultramarathon.

Creatine kinase (CK) is an enzyme that is released into the blood following muscle breakdown. Outside of exercise, a CK greater than 1,000 U/L (units per liter) is concerning for rhabdomyolysis. Following exercise, however, there is no consensus about a threshold CK level that is concerning. Indeed, after an ultramarathon, a CK of greater than 100,000 has been frequently observed without apparent health consequences (Hoffman, 2012).

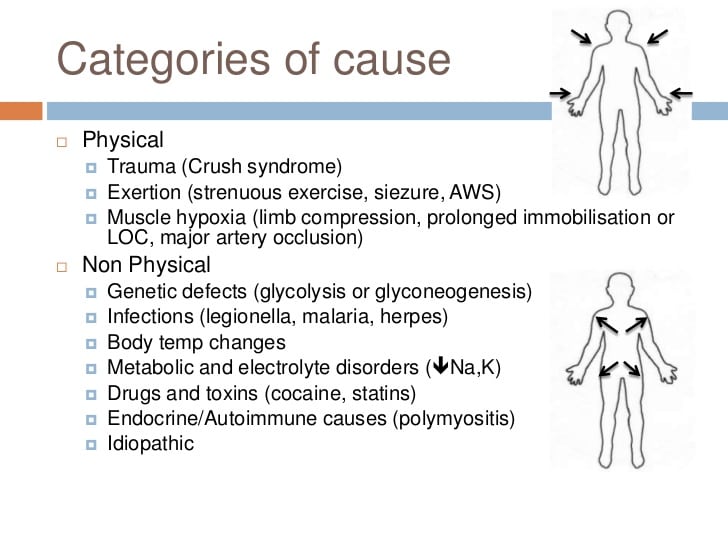

While there are many causes of rhabdomyolysis (see Figure 1), some related to exercise and some not, for the purposes of this article, we are discussing the syndrome of exercise-related rhabdomyolysis, better known as exertional rhabdomyolysis.

In order to diagnose exertional rhabdomyolysis, or what some refer to as “clinically significant exertional rhabdomyolysis,” it is generally agreed upon that one must have BOTH a laboratory value showing excessive muscle breakdown and the “appropriate clinical presentation.” This clinical presentation could include muscle pain, stiffness or weakness out of proportion to the exercise performed, or “cola-colored urine*” (Szczepanik, 2014).

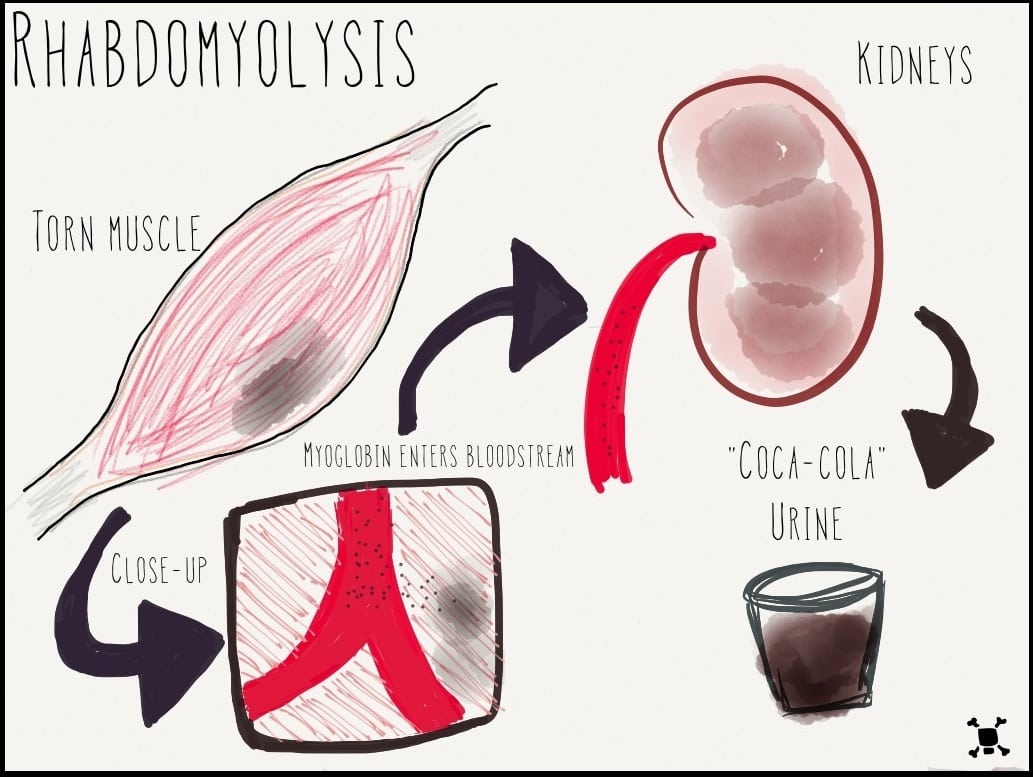

*Cola-colored urine is caused by myoglobin, a protein released during muscle breakdown that, if present in a high-enough amount, gives the urine a cola color. Of note, though, myoglobin is also expected to be elevated following an ultramarathon. Indeed, 33 of 34 test subjects who had just completed the London Marathon had elevated myoglobin levels to the point that it was above the laboratory’s measurable range (Smith, 2004).

Why is Rhabdomyolysis Potentially Dangerous?

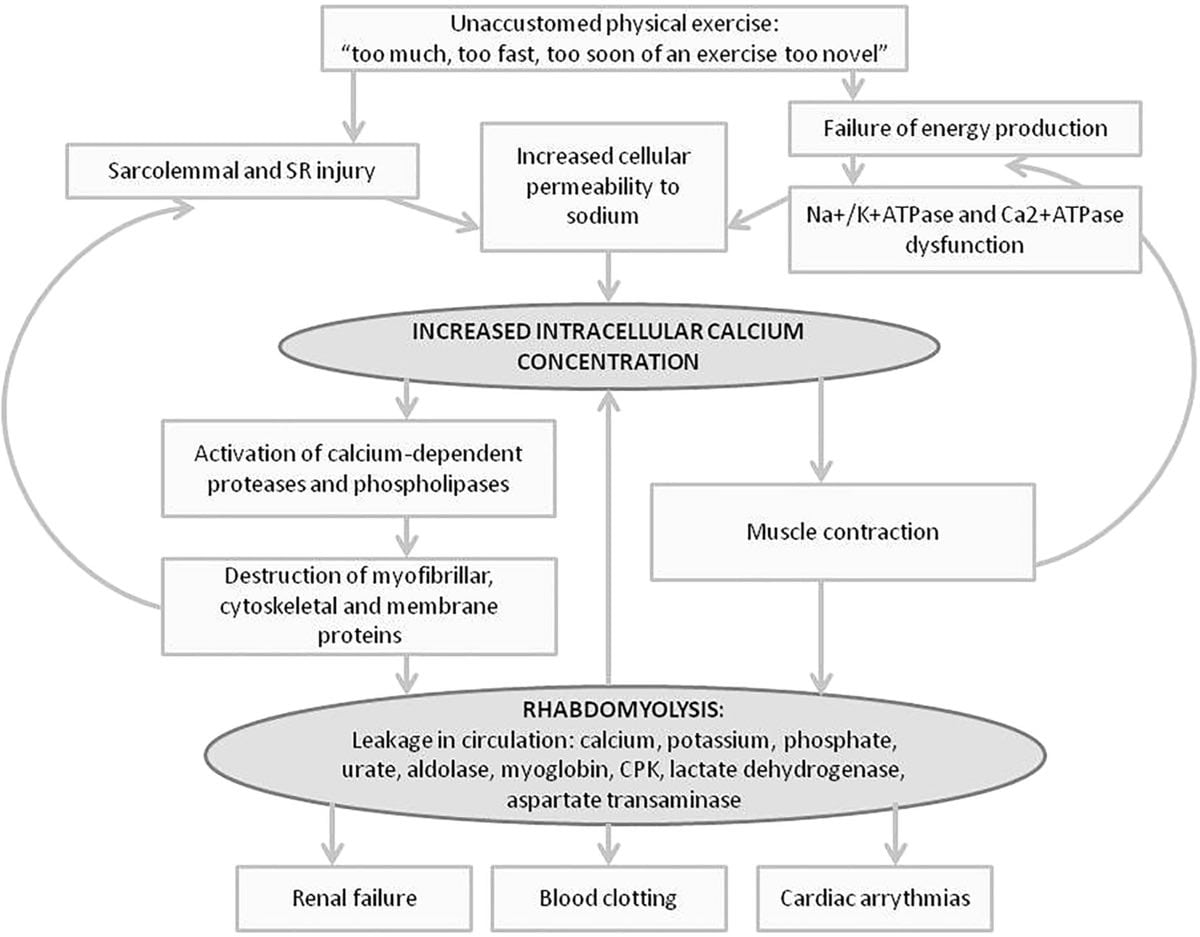

When skeletal muscle cells break apart, they release electrolytes and myoglobin (see Figure 3). As previously mentioned, myoglobin is a protein that is not normally found in the blood that, when released from broken-down muscles, can precipitate (crystallize) and block the tube-like filters of our kidneys, causing urine to appear like cola. A sufficiently large amount of myoglobin can damage the kidneys to the extent that they stop functioning entirely. Also, electrolytes like potassium and calcium can build up in the blood and put a person at risk of irregular heartbeats (which, in the worst circumstance, can stop the heart).

Figure 3. A detailed diagram showing how exercise can cause damage to muscle cells and how these damaged muscle cells release toxic molecules and electrolytes which can lead to kidney damage, easy blood clotting. and an irregular heart rhythm.

History

Rhabdomyolysis was initially called “crush syndrome,” when in 1940, during the London Blitz of World War II, a large number of peoples’ limbs were crushed. These patients survived the crushing, only to die of kidney failure several days later. The causes of rhabdomyolysis are numerous and can include direct muscle injury (e.g., electrocution, burns, etc.), loss of blood flow to muscles, infections, muscle and immune-system disorders, drugs (e.g., statins), toxins (e.g., hemlock, toxic mushrooms), and some venoms. And many different genetic conditions can predispose a person to the development of rhabdomyolysis.

Risk Factors for Exertional Rhabdomyolysis

- Unaccustomed and/or eccentric exercise

- Heat, cold

- Dehydration (and possibly overhydration while racing)

- NSAID use (Farquhar, 1999; Hodgson, 2017)

- Other medications listed in Figure 4

- Current infection

- Male sex

- Genetic predisposition

Figure 4. Drugs that can cause rhabdomyolysis (even in the absence of exercise). Figure courtesy of Dr. Xenia Klein.

Classically, exertional rhabdomyolysis occurs with excessive and/or repetitive exercise, particularly with significant eccentric exercise. (Eccentric contraction happens when a muscle lengthens despite contraction, such as the quadriceps when running downhill.) There are approximately 26,000 cases of exertional rhabdomyolysis yearly in the U.S. that necessitate hospitalization (O’Connor, 2012). There have been ‘outbreaks’ related to extreme exercise, such as repeated triceps drills and pushups in football players and upper-extremity exercises in swimmers, to name a few. And the New York Times recently published an article about the rise of rhabdomyolysis after spinning classes, CrossFit, and other ‘weekend warrior’ activities.

The author of this article personally developed rhabdomyolysis after holding a surgical retractor in the same position in the operating room during a 12-hour surgery. I did not drink or eat during the entire case. Being the wise runner that I am, I immediately went out for an hour-long run, only to start peeing cola-colored urine when I got home. I was a medical student and knew enough at the time to be concerned about rhabdo. To be on the safe side, I went to the emergency room, where myoglobin was found in my urine. I received a bag of intravenous (IV) fluids and, when I started peeing yellow, was released home.

Ultrarunning-Specific Research

Despite the excessive, prolonged exercise involved in running an ultramarathon, it typically does not result in clinically significant exertional rhabdomyolysis. In other words, there can be evidence of significant muscle breakdown, but no signs of detrimental health effects. And, to my knowledge, no deaths have occurred due to ultramarathon-related rhabdomyolysis. That is not to say that exertional rhabdomyolysis does not happen in ultrarunners; however, the diagnosis of exertional rhabdomyolysis (that is significant) is very challenging given the laboratory values typically used to diagnose exertional rhabdomyolysis are expected to be abnormal after an ultramarathon.

Again, a CK greater than 366 U/L for adult men and greater than 176 U/L for adult women is considered abnormal in a resting state and a CK greater than five times the upper limit of normal is diagnostic for non-exertional rhabdomyolysis. We know, for example, from the 2010 Western States 100 that the average CK blood level immediately post-race was 32,965 U/L and ranged from 1,500 to 264,300 U/L. No cases of acute kidney injury were reported from that year.

It can also be difficult to know when a runner crosses the line from a normal physiologic response to running an ultramarathon to exertional rhabdomyolysis. For example, delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS), experienced a day or so after strenuous exercise, is an indicator of muscle damage and signifies a very mild form of rhabdomyolysis. However, this only becomes worrisome when the pain is severe, you start having cola-colored urine, or you start swelling or stop peeing (the latter two suggesting possible kidney failure). Kidney failure is also very rare (only 19 cases among more than 100,000 runners of the Comrades Marathon over 18 years) and it is not known how often rhabdomyolysis is the cause of this kidney failure.

We know from unpublished 2017 Western States 100 data (Høeg & Warrick, unpublished data) that there were no known cases of clinically significant exertional rhabdomyolysis among research participants and there was no obvious relationship between the level of CK post-race and estimated kidney function (see Figure 5). (Note, again, CK levels greater than 100,000.)

Figure 5. 2017 Western States kidney function (shown as eGFR or the rate at which the kidney is filtering) immediately post-race was not significantly correlated with CPK (aka CK) levels. Of the participating runners in our 2017 study, none developed kidney failure.

Basically, what this graph shows is you can have a heck of a lot of muscle breakdown without any obvious effects on your kidneys, at least at the finish of an ultramarathon.

However, kidney failure can still occur a couple days later, at which a person could be diagnosed with rhabdomyolysis-induced kidney failure if the CK is still elevated and/or there is myoglobin in the blood or urine. Unfortunately, post-race CK levels have not been shown to be helpful in predicting who will go on to get kidney failure (Brusso, 2010). If you are concerned about kidney injury following an ultra, a urine dipstick done post-race has been found to be helpful in predicting who might go on to develop kidney failure (Hoffman, 2013); if you are concerned about kidney failure or rhabdomyolysis post-race, this is a good screening test but is generally not available at a race’s finish line.

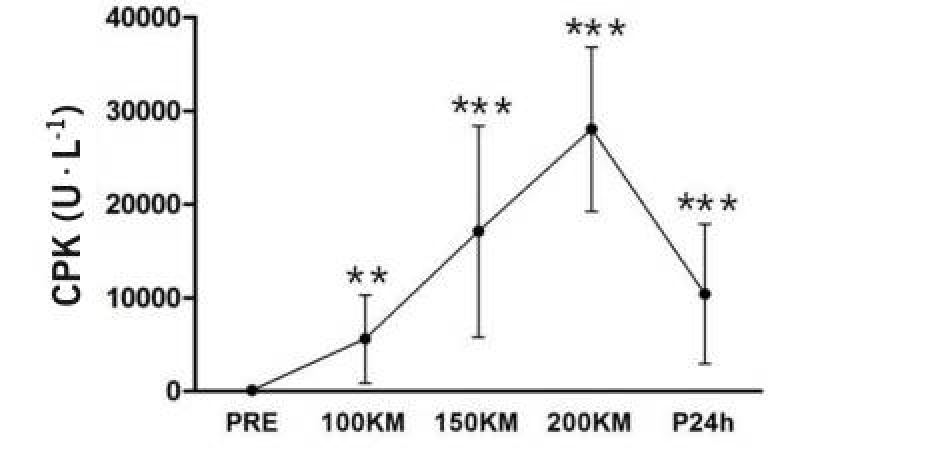

Data from a 200-kilometer race in Ceju, South Korea (see Figure 6) indicated that CK, on average, decreases significantly 24 hours post-race. They postulate this may be due to increased clearance of breakdown products because of improved hydration post-race more than an actual decrease in muscle breakdown. These data suggest that, if there is no kidney failure, that CK continues to fall post-race, at least at 24 hours post-race.

Figure 6. CPK (aka CK) levels as measured before, at 100k, 150k, the 200k finish line, and 24 hours post-race (Son, 2015).

In other words, what this research tells us is that a CK level that continues to rise greater than 24 hours post-race is concerning, as it may be a sign that the kidney is not filtering out the CK as it should (Scalco, 2016). Two signs that your kidneys might not be functioning properly are no or very little urination or generalized swelling.

Fictional Clinical Scenarios Pop Quiz

Let’s consider the stories of three racers completing a 100-mile race. Which one of these has/have exertional rhabdomyolysis?

Runner A finishes a 100-mile race in 28 hours and on post-race blood draw is found to have a CK of 104,000. He otherwise feels tired and sore, has a blister on his foot, but no other complaints.

Runner B finishes the same 100 miler and collapses, complaining of severe fatigue and whole-body aching. You are not able to obtain blood for a blood draw, but he is peeing cola-colored urine and he has myoglobin in his urine.

Runner C finishes the 100-mile race and is throwing up and has trouble walking straight. You also get a post-race blood draw on him and his CK is 55,000 and his sodium is very low. His kidney function is normal.

The answer is B. This is important, because this person needs to be sent to a hospital. Provided their sodium is not too low, they should receive IV fluid treatment and additional testing of electrolytes and kidney function.

Runner A has no worrisome symptoms and an elevated CK alone is not sufficient to warrant any further work-up or treatment at this time.

Runner C has exercise-associated hyponatremia (low sodium), which is life threatening and, very importantly, despite the elevation in CK, this person should not receive isotonic IV fluids for his CK because this could actually lower the sodium further and cause pulmonary edema, seizures, or death. Hypertonic (3%) saline IV fluid should be given in this case.

It should be noted that runners can and do get hyponatremia and rhabdomyolysis together (Brusso, 2010; Chlibova 2105; Hoffman, 2015; Putterman, 1993)

Did JH Have Rhabdomyolysis?

JH was brought in for medical care around 24 hours after his race finish. He had not peed since early in the the race. The medical personnel assumed he was dehydrated given the race distance/time and that he was vomiting. They gave him one bag of IV normal saline after another. He became progressively nauseated and swollen. Then he got short of breath. Around this time, his initial lab results came back and he had critically low sodium. He was then transferred emergently to a critical-care center, where in addition to the critically low sodium, he was found to have elevated CK, myoglobin in his blood, and significant kidney damage. He began to develop significant muscle pain over the next few days. He went on to require dialysis until, thankfully, his kidney function returned weeks later. He said that, the first time he peed, it was cola-colored.

What can we learn from JH’s case?

Clinically significant exertional rhabdomyolysis can occur following an ultramarathon, though it may be more likely or equally likely to occur with overhydration as dehydration (Brusso, 2010; Chlibova 2105; Hoffman, 2015; Putterman, 1993). The extreme effort, long duration, and large amount of eccentric movement while running in the mountains, in addition to admitted NSAID use among many ultra participants, were all likely risk factors for rhabdomyolysis in this case. Drinking despite not being thirsty (even with the addition of salt tabs) likely worsened the low sodium level. It was not entirely clear whether the low sodium from overhydration or the muscle-cell breakdown comes first, but it has been proposed that low-sodium levels cause muscles cells to break down easier (Chlibova, 2015; Noakes, 2012). Alternately, the inflammation of the muscle breakdown may worsen the hyponatremia (low sodium). Perhaps it was a case of a vicious cycle with JH.

When Should Runners Worry About Exertional Rhabdomyolysis and/or Kidney Injury?

- You finish a race and you do not pee for more than 12 hours. (This could indicate kidney failure, potentially due to muscle breakdown plus or minus dehydration.)

- You are experiencing muscle soreness out of proportion to that expected from the race you just ran. This could indicate muscle breakdown significant enough to cause kidney damage and/or electrolyte abnormalities.

- You are peeing cola-colored urine. This is likely from myoglobin leaking from your muscles, through your kidneys, and into your urine. It may also be a sign of accompanying dangerous electrolyte abnormalities.

Loss of balance, control of your limbs, nausea, water aversion, headache, and seizures are all potential signs that you have exercise-induced hyponatremia (low sodium). This is life threatening and should not be treated with normal (isotonic) saline IV fluids (which could be fatal), but 3% hypertonic saline should be used. Sodium levels must be checked in any runner who is suspected of having rhabdomyolysis before IV fluids are given.

How Can You Prevent Exertional Rhabdomyolysis Plus or Minus Kidney Injury in Ultrarunning?

- Train for the terrain you plan to run in. Repetitive unfamiliar stress to any muscle group can set you up for rhabdomyolysis.

- Drink when you are thirsty (avoid dehydration and overhydration) and do not drink if you are not thirsty to avoid developing a low sodium level.

- If you have developed exertional rhabdomyolysis plus or minus kidney failure before, avoid use of NSAIDs while racing. If you have not had exertional rhabdomyolysis, use them very judiciously, if at all, while racing. NSAIDs decrease the kidney’s ability to clear waste products from the blood stream (Farquhar, 1999) and increase the risk of kidney injury (Lipman, 2017).

- If you are on any prescription medications, determine with your doctor if they are associated with an increased risk of rhabdomyolysis (see Figure 3 above).

- If you have a fever or systemic infection with or without fever, you are in a pro-inflammatory state, putting yourself at higher risk of exertional rhabdomyolysis and probably should not be racing while your body is attempting to recover.

- If you have had recurrent exertional rhabdomyolysis, especially with low amounts of physical activity, seek medical assistance in figuring out why.

Additionally:

- A CK that does not return to less than five times the upper limit of normal despite two weeks of rest will require further work-up for genetic predisposition to exertional rhabdomyolysis.

- If you or someone in your family has sickle-cell trait (or disease), you are at much higher risk of developing severe and recurrent rhabdomyolysis. If recurrent rhabdomyolysis runs in your family, you may consider genetic testing to learn why and if you are at risk.

- Please also note that salt tabs and salt supplementation have not been found to be effective or necessary in the prevention of exercise-associated hyponatremia. The most important treatment is to avoid drinking if you are not thirsty. Low sodium tends to happen because of overhydration.

Call for Comments

Have you experienced race-related rhabdomyolysis and/or kidney failure? Please share your story with us so we can learn more about this still somewhat enigmatic entity in long-distance runners.

References

Bruso J.R., Hoffman M.D., Rogers I.R., Lee L., Towle G., Hew-Butler T.

(2010) Rhabdomyolysis and hyponatremia: A cluster of five cases at the 161-km 2009 Western States Endurance Run. Wilderness and Environmental Medicine, 21 (4) , pp. 303-308.

Chlíbková, Daniela et al. “Rhabdomyolysis and Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia in Ultra-Bikers and Ultra-Runners.” Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 12 (2015): 29. PMC. Web. 15 Feb. 2018.

Farquhar WB, Morgan AL, Zambraski EJ, et al. Effects of acetaminophen and ibuprofen on renal function in the stressed kidney. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:598–604.

Harpaz, Rave & DuMouchel, William & Shah, Nigam & Madigan, David & Ryan, P.B. & Friedman, Carol. (2012). Novel Data-Mining Methodologies for Adverse Drug Event Discovery and Analysis. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 91. 1010-21. 10.1038/clpt.2012.50.

Hodgson L, Walter E, Venn R, et al Acute kidney injury associated with endurance events—is it a cause for concern? A systematic review BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2017;3:e000093.

Hoffman, Martin D. et al. Increasing Creatine Kinase Concentrations at the 161-km Western States Endurance Run. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine , Volume 23 , Issue 1 , 56 – 60

Hoffman MD, Stuempfle KJ, Sullivan K, Weiss RH. Exercise-associated hyponatremia with exertional rhabdomyolysis: importance of proper treatment. Clin Nephrol. 2015;83:235–42.

Hoffman MD , Stuempfle KJ , Fogard K , et al . Urine dipstick analysis for identification of runners susceptible to acute kidney injury following an ultramarathon. J Sports Sci 2013;31:20–31

Høeg T, Warrick A. Creatine phosophokinase levels vs. estimated kidney function at Western States 100 mile run 2017. In preparation for publication.

Lipman GS, Shea K, Christensen M, et al Ibuprofen versus placebo effect on acute kidney injury in ultramarathons: a randomised controlled trial Emerg Med J 2017;34:637-642.

Noakes T. Waterlogged. Human Kinetics: The serious problem of overhydration in endurance sports. New Zealand; 2012.

O’Connor FG, Deuster PA. Rhabdomyolysis. In: Goldman’s Cecil Medicine. 24th ed. Goldman L and Schafer AI. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2012.

Putterman C, Levy I, Rubinger D. Transient exercise-induced water intoxication and rhabdomyolysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1993;21(2):206–9.

Scalco RS, Snoeck M, Quinlivan R, et al Exertional rhabdomyolysis: physiological response or manifestation of an underlying myopathy? BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2016;2:e000151.

Smith JE, Garbutt G, Lopes P, et al Effects of prolonged strenuous exercise (marathon running) on biochemical and haematological markers used in the investigation of patients in the emergency department British Journal of Sports Medicine 2004;38:292-294.

Son H, Lee Y, Chae J, Kim C. Creatine kinase isoenzyme activity during and after an ultra-distance (200 km) run. Biology of Sport. 2015;32(4):357-361.

Szczepanik, Michelle E. MD1; Heled, Yuval PhD, FACSM2; Capacchione, John MD3; Campbell, William MD4; Deuster, Patricia PhD, MPH5; O’Connor, Francis G. MD, MPH. Exertional Rhabdomyolysis: Identification and Evaluation of the Athlete at Risk for Recurrence. Current Sports Medicine Reports13(2):113-119, March/April 2014.