When Abby Hall won the 2025 Western States 100, it was easily the comeback story of the year: A runner on an upward trajectory to success derailed by a broken leg during a freak training accident returns to win one of the biggest races in ultrarunning.

The performance came as a surprise to many. And Hall says that for much of her running career, “I got really used to being in this position of someone who is on the edge of a breakthrough yet never actually doing it.” But looking at Hall’s approach to running, and her commitment to the sport over nearly a decade of ultras, it seems like it likely wasn’t a matter of if, but when her breakthrough would happen. She says, “I find my new north star every year or two and just go all in.” After fracturing her tibial plateau in a training accident about a week before the 2023 Western States 100, yet still attending the race to watch her friend and teammate Tom Evans win that year, the event became her guiding light during the tough times of injury, surgery, and a long recovery.

The Western States 100 wasn’t the first star she’s chased. Before Western, it was the Leadville 100 Mile. Before that, the fastest known time on the John Muir Trail, and even before that, the elusive summit of Longs Peak in Colorado — as a child. Regardless of the goal, Hall has continually been willing to put everything on the line to reach it.

Early Personality

Hall grew up in the Chicago, Illinois, area, with a few-year stint in Vermont during middle school and summer family trips to Estes Park, Colorado, the latter of which especially allowed her to become immersed in the outdoors. An only child, Hall says her earliest memories are of her family’s “annual pilgrimages out in the minivan to Estes Park,” Hall says that during these one- to two-week camping trips, some of her core personality traits were already showing. She tells a story about how, when still very young, she proudly proclaimed to the home camera that she’d hiked five miles. “I was already tracking miles,” she laughs.

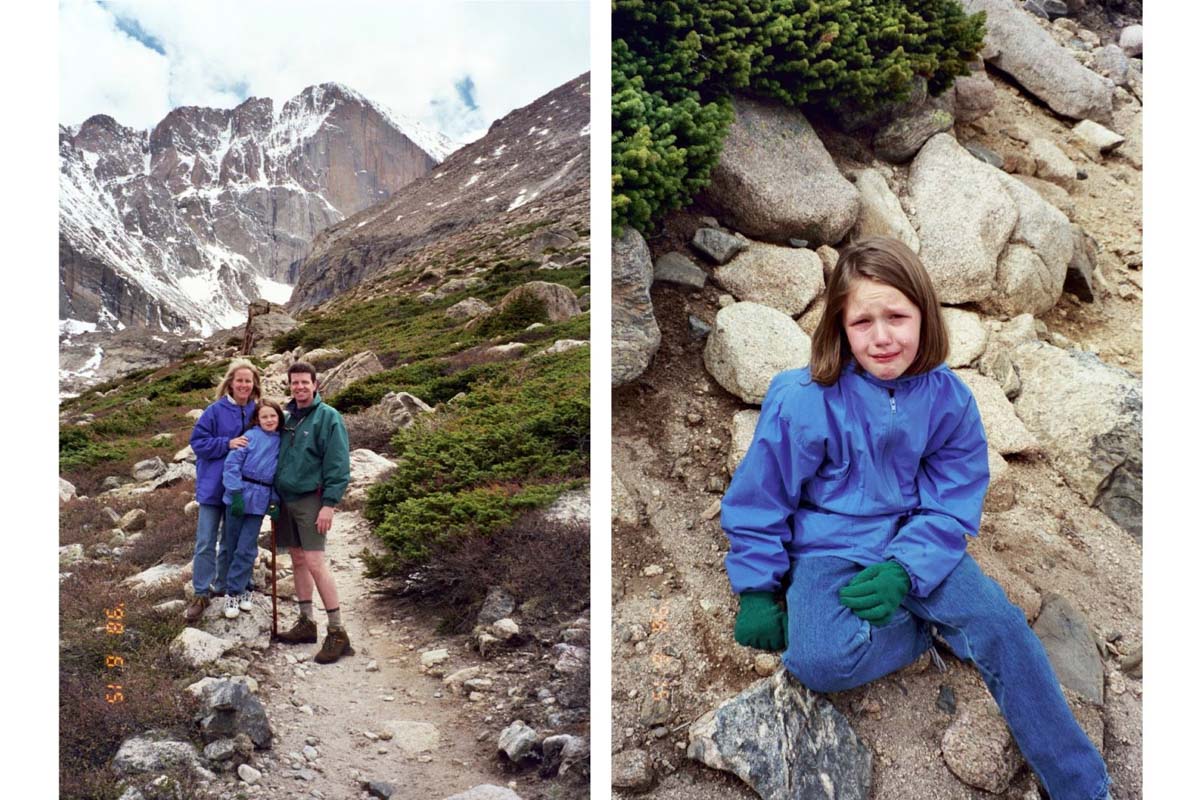

Left: Hall and family in front of Longs Peak in Colorado. Right: Hall crying because she had to turn around on the trail. All photos courtesy of Abby Hall unless otherwise noted.

Her parents quickly realized they had an intrinsically motivated child on their hands. Hall says, “If I was ever lagging behind, they discovered that if they told me to lead the way, then suddenly I was marching to a new drum beat.” Reflecting on it, Hall says, “I appreciate, in hindsight, that at an early age, my parents gave me opportunities for those small moments of ownership.”

Longs Peak, a 14,258-foot mountain towering over Estes Park, became a prominent fixture in Hall’s life as her parents would take her farther up the trail toward the summit each year. Hall says, “My mom has family photos of me crying every time we would have to turn around.” Around fifth grade, Hall recalls the turnaround being especially difficult, “I took a rock back with me, and it was like my penance. I was like, ‘Remember, you had to turn around and let this rock remind you all year of how hard you want to work to come back and make it higher on the mountain next year.’” Hall laughs with the sidenote of, “I wouldn’t condone taking rocks from the trail now, but I was a kid.”

It wasn’t until after college that Hall would eventually make it to the top of Longs Peak, a childhood dream fulfilled.

A Love of Running

Around fifth grade, after the family moved to Vermont, Hall started joining her mom for short neighborhood runs. As a pre-teen, Hall was eager to explore her surroundings. “I think running became a fun way for me to develop some autonomy at that age when you’re on the cusp of being able to start doing some things by yourself,” Hall says. “I remember loving that independence of, ‘I’m going to plan a route, and I’m going to go do this route, and it’s going to be three miles.’” Hall was already tracking her training, and says, “I had my little running log and was writing down what I ran each day.”

That year, her family signed up for a summer race series, and Hall loved it. She’s quick to point out that it was hard not to love it at that age, saying, “They really incentivize you because there will be the 13-and-under category, and if there are two kids that show up and you beat the other kid, you’re a winner, and you get a pie!”

According to Hall, running was a social and lighthearted activity. “I really just loved the fun of going off with my friends after school and running in the woods, and maybe we’d throw a couple bucks in our pockets for a Slurpee or a Coke at 7-Eleven, and sneak it on the way back.”

By high school, Hall had moved back to Chicago, and running had her full attention. She says, “High school running is where I developed a real discipline and structure for pursuing goals. I lived and breathed cross country and track.” Running was all-immersive, and she says, “My teammates were my best friends, and my coach was a hugely influential part of who I am now.” These days, she still thinks of the lessons he taught, including, “It’s what we do when nobody’s watching.” She pauses, reflecting on the idea, and laughs, “ I think he mainly said this so that we wouldn’t drink when we were on spring break.”

The lessons stuck, though, and she says, “I think he really instilled this work ethic of champions are built in those quiet moments, those runs you don’t want to do, finishing strong on that last interval, those small moments.” Of the time period, Hall says, “It was like the first time I felt like I was choosing excellence for myself.”

Discovering Trail Running

Still in Chicago, Hall ran through the first three years of college, and she took her senior year off to focus on her capstone art show. She spent part of that year in Italy and started to take ownership of her running after years of structured training. She says, “I remember I would do my studio time all day and then just run in Florence in the late afternoon, early evening. It was the first time that I felt like I was choosing how far I wanted to run and what felt good.”

After graduation, Hall took a job as a graphic designer in Chicago, and her running consisted of night runs along the shore of Lake Michigan. But it wasn’t long before the draw of the U.S. West became too strong, and after a trip to a music festival in California, her decision was made. She says, “I was like, ‘California is great. I’m moving to California.’ And I think a month later, I packed up my car and moved, pretty much on a whim. I just knew I wanted to be out West.”

Still living in the urban environment of Los Angeles, Hall had yet to realize that she could take her running, which she did on the roads and through racing marathons, to the mountains, where she’d go to climb and camp on weekends.

It was a trip up Mount Whitney that eventually allowed her brain to connect the two activities. She got a permit to climb the mountain, and as she puts it, “I filled up my pack like a total idiot. I filled up my bear box with fresh fruit and was just a total novice. I brought a hardcover book with me and did Mount Whitney over two days. I ran out of water, got caught in a storm on the way down, and learned a lot. I just remember calling my mom traumatized on the drive home, being like, ‘I’m never doing that again.’”

It only took a week of recovery before Hall started digging into how fast other people could do the mountain, which led to her discovering the idea of a fastest known time attempt on the 214-mile John Muir Trail, which started down the other side of Mount Whitney. That same digging led Hall to discover the world of ultrarunning. “I was Googling and I distinctly remember listening to one podcast, a Way Too Cool 50k preview. I was like, ‘I don’t even know what Way Too Cool is. What do they mean? A preview of the course?’ And they’re talking to all these different athletes, and I had discovered this whole new world for the first time.”

Hall says the idea of a speed attempt on the John Muir Trail was also “rapidly taking root over my whole personality.” She left Los Angeles in 2016 and moved to Boulder, Colorado, to position herself better for training and pursuing her dream.

The John Muir Trail and Ultrarunning

Hall immediately immersed herself in the Boulder running scene. She says her approach was to go to group runs and “just basically be like, ‘Hey, I’m Abby. Want to be friends?’” Still new to ultra distances and with the John Muir Trail in her sights, Hall says, “I came up with what I thought was a bulletproof plan of my first 50-kilometer race in June, first 50 miler in July, and then another 50k in August, and then the speed attempt in September.” Through the group runs, Hall soon met her future husband, Cordis Hall, and offered to buy him a plane ticket to California if he’d come support her on the John Muir Trail.

The attempt did not go as planned. Hall says, “I think I got it about 45 miles in before I was like, ‘I’m not at all ready for this. This is very advanced.’” The experience provided a new perspective and motivation, and Hall says, “It left me totally heartbroken, and I was immediately eager to improve on the areas that I felt like I needed experience in.”

Running ultras seemed like the logical way to get better at the distances she’d need to be able to cover for the John Muir Trail. At the time, Hall was frequently running with Cat Bradley and Clare Gallagher. Early on in their friendships, Gallagher won the Leadville 100 Mile in 2016, and Bradley won the Western States 100 in 2017. Hall quickly got immersed in high-level running, and big performances were normalized in her running circles. She says, “In Boulder, especially during that era, I think racing at a high level felt incredibly accessible.”

According to Hall, running with the likes of Gallagher and Bradley may have given her a false sense of confidence at the 2017 Leadville 100 Mile, her first attempt at the distance. She says, “I went into Leadville with this fever for ultra, and I was, ‘Cool, I can win this thing.’” She laughs, “I got absolutely rocked by it, and I was the fourth-to-last-place woman.” Heartbroken and humbled yet again, she decided to devote the next year of her life to improving at the event. She hired Jason Koop as her coach and started training.

She went back to Leadville in 2018 and admits, “I got totally rocked again. I think I improved by maybe a half hour.” Koop didn’t sugarcoat his evaluation of the performance, and Hall says, “He warmly pointed out that it was more or less the same kind of performance as the year before, and we still had work to do.”

Successes and Setbacks

In the years since those fateful Leadville 100 Mile performances, Hall has slowly risen in the ranks of ultrarunning with notable successes including placing second at the 2021 Canyons 100k, two top-three finishes at CCC in 2021 and 2022, a win at the 2022 Transvulcania, and second-place at the 2022 Transgrancanaria. Then, in an accident involving a hyperextended knee during a routine training run, she fractured her tibial plateau and damaged the tendons and ligaments around her knee. The damage was repaired in a serious surgery, and multiple years of healing and rehab followed.

Hall coming into Pointed Rocks at mile 93 of the 2025 Western States 100, paced by husband Cordis Hall.

If that wasn’t enough, she also had a large blood clot form in the aftermath. She says that when her health care provider found it, they said, “This was probably a matter of a day or so before it would have made its way to your lungs and heart.” Reflecting on it, Hall says, “That was really scary and took the injury to a whole new place of fearing for my overall health. It added a lot of emotion to an already challenging time.”

But just more than two years after what could have been a career-ending accident, Hall lined up for the 2025 Western States 100 and won with the fourth fastest women’s time in the history of the event.

Lessons Learned for the Future

Hall says that coming back from the injury was the hardest thing she’s ever done, but that it changed the way she thought about running. She says that returning to training, “There’s a certain ease that I think I’ve been able to move through things that previously felt hard to me. The injury probably influenced me in far more ways than I am even perceiving.”

She continues, “What it did was elucidate how pure and deep my love for running was. It stripped away a lot of the BS that can so easily cloud our running, whether that’s overly focusing on extrinsic outcomes or comparing ourselves to others, which can be detrimental. All of those things can so easily get in the way of remembering the joy and the simple act of putting one foot in front of the other.”

When Hall lines up for the 2026 Black Canyon 100k this February and the 2026 Western States 100 this June, it’ll be with a lot of lessons learned over the years. She says, “The biggest thing my injury has taught me is the preciousness of now, and that this doesn’t last forever. I’ve had that more front of mind than ever.”

And as for a John Muir Trail attempt later in the year, chasing the north star that first brought her to trails? Hall definitely hasn’t taken that off the table.

Call for Comments

- Share an Abby Hall story with us!

- What north stars have guided your own running?