Like for many of us, for Nicholas Thompson, running isn’t just about running. In his new memoir, “The Running Ground,” which was released on October 28, Thompson — the CEO of “The Atlantic,” a cancer survivor, the 50k American record holder for the men’s 45-to-49 age group, and a lifelong runner — examines his sometimes complicated personal history of the sport and the ways it has interwoven through the other aspects of his life. From running with his father, with whom he had a seemingly difficult and complex relationship, to using running to navigate recovery from thyroid cancer, to diving deep into training with Nike to try to run the Chicago Marathon in a new personal best at the age of 44, Thompson explores how this simple sport has driven, dictated, and helped him navigate the bigger questions in life. Thompson runs left foot, right foot, to the tops of mountains and the finish lines of marathons, but the key questions that the book grapples with go far beyond simple movement. Running is simply one of the threads that binds the various stories of Thompson’s life, including his relationships with his father and his sons, as well as his own mortality, together.

Like for many of us, for Nicholas Thompson, running isn’t just about running. In his new memoir, “The Running Ground,” which was released on October 28, Thompson — the CEO of “The Atlantic,” a cancer survivor, the 50k American record holder for the men’s 45-to-49 age group, and a lifelong runner — examines his sometimes complicated personal history of the sport and the ways it has interwoven through the other aspects of his life. From running with his father, with whom he had a seemingly difficult and complex relationship, to using running to navigate recovery from thyroid cancer, to diving deep into training with Nike to try to run the Chicago Marathon in a new personal best at the age of 44, Thompson explores how this simple sport has driven, dictated, and helped him navigate the bigger questions in life. Thompson runs left foot, right foot, to the tops of mountains and the finish lines of marathons, but the key questions that the book grapples with go far beyond simple movement. Running is simply one of the threads that binds the various stories of Thompson’s life, including his relationships with his father and his sons, as well as his own mortality, together.

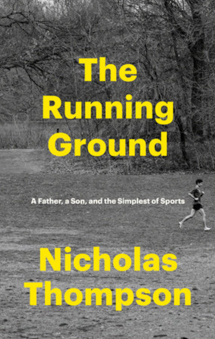

Author Nicholas Thompson, who is also the CEO of a major magazine, a father, a son, and a runner. Photo: Sarah Stafford

This memoir is wonderfully multifaceted. Over a series of days after finishing it, the book’s perspectives and anecdotes have floated to the surface of my mind, and I’m staggered that they’re all from the same piece of work. I think of one story in particular as I shut myself away to get my thoughts in order to write this review. When the tragic Boston Marathon bombing happened in 2013, Thompson was working for “The New Yorker,” managing the website. Editor-in-Chief David Remnick appeared at his office door and told him to write a story on the bombing, telling Thompson: He was a runner, these were his people. Thompson protested: “I had much more confidence in others to write about this than I had in myself.” Remnick’s response was to tell him to close his office door, turn off his phone, and write the piece. He would be back in an hour.

As I sit down to write this piece and am mulling over the impact of the death of Thompson’s father on his life, I remember that Thompson himself survived thyroid cancer. While I’m thinking about his decision to DNF the 2022 Tunnel Hill 50 Mile race, I remember that this is a man who ran a 2:29 marathon in 2019 at the age of 44. He set the American record in the 50k in the men’s 45-to-49 age group in 2021. I come back to the anecdote of Thompson having to put his head down and write the story about the Boston Marathon bombing and find in it the same diligent discipline that has been key to Thompson’s success in running. These seemingly disparate strands that make up a life, when knit together, make for an expansive, rich, yet erudite story.

Throughout the book, Thompson, who now has sons himself, grapples with his relationship with his own father, who was also a talented runner. He examines how much of his success in running, from setting a class record in the two-mile event in high school and beyond, came from his father. Didn’t he inherit those genes? What else did he inherit? What is he passing on to his own sons?

Like his son, Thompson’s father, W. Scott Thompson, had many facets to him. He was gay but had always wanted a son, and he left the family when Thompson was a child. The first part of his life was spent as a professor of Southeast Asian studies at the Fletcher School at Tufts University. According to Thompson, his father was an alcoholic, a sex addict, and spent the latter years of his life in Asia running a “male brothel.” Thompson’s father was often in financial difficulty and asked his children for money. When they refused, he would threaten to kill himself. Thompson would relent, and the cycle would continue. Despite all of this, Thompson alludes to a closeness and a deep love between them. They ran together, they worked together, they hosted dinner parties together. A parent’s pride is precious and grounding, and there are heart-rending moments as Thompson comes across evidence of his father’s admiration in letters and keepsake articles.

Thompson understands that running is a theme that exists between himself and his own sons as well. When, after a race, one son sees his father’s broken form on the living room floor as inspiration to start running, another swears he will never run a race at all. They seem proud of him, but sweetly, at the age of eight, one son declares, “You should train harder when I’m not home, and not at all when I am.” Balancing family, work, and running life is a constant, delicate battle throughout the memoir. When father and sons get to run together, it doesn’t feel like a ceremonial passing of the torch. It just feels like a fact of nature and nurture. The tone of the book is extremely ordinary, quintessentially human, and intrinsically grounded in reality.

In addition to using running to examine his own relationships, Thompson also uses it to confront his own mortality. Thompson’s thyroid cancer diagnosis came somewhat out of the blue in 2005 when he was just 30 years old. His goal after treatment was to get back to running as fast as he had before the cancer. Running a fast marathon would be confirmation that he had recovered. “Every year I could run that speed was another year that I knew I was still alive,” he says. Life continued on.

Then in 2017, Thompson’s father died, and soon after, he got the chance to train for the Chicago Marathon with the support of a full team from Nike. Throughout the training process, Thompson gives a great deal of credit to the peace of handing his race over to data, to coaches who had it all in hand and who guided him through a new and seemingly intense regime. It was a release of control. Thompson reflects on the death of his father just as meaningfully.

There is a lot to consider here in questions around death, mortality, control, and acceptance. With the cancer and his father gone, Thompson found a new version of himself. This version was free to run 2:29:13 at the 2019 Chicago Marathon, which, at age 44 and after a lifetime of running, was a new personal best.

Mortality feels very in vogue at the moment, and ideas around longevity and optimising lifespan have been circulating in all sorts of corners of art, culture, media, science, and technology. This book is rather confronting, but in all its vivid reality and its humble clarity, “The Running Ground” is extremely life-affirming. It has inspired me to run toward the next version of myself, whatever way the threads weave. It feels — ironically — timeless.

Call for Comments

- Have you read “The Running Ground,” and if so, what did you think?

- Do you find that the different facets of your life are bound together by running?