Returning to running after an injury can be challenging and full of unknowns. When do you rest and how much? Then, when do you return to running? How much is too much or not enough? Are some types of pain ok?

Returning to running after an injury can be challenging and full of unknowns. When do you rest and how much? Then, when do you return to running? How much is too much or not enough? Are some types of pain ok?

Many run-walk and pain guide recovery protocols fall short when it comes to providing guidance on returning to running after an injury, as they don’t account for the fact that some pain might be a requirement for full recovery. The ideal amount of tissue loading for rebuilding is critical. Recovery requires activity that both strengthens healing tissue and also provides a critical remodeling stress that helps restructure repaired-but-inefficient connective tissue into coherent, strong, mobile, and pain-free structures. And sometimes, this process is painful.

Balancing loading and pain management is a delicate and often frustrating process. How do you apply enough stimulus for positive effects without overloading, which could reverse progress? How does a runner determine, for their specific injury, body, and lifestyle, what amount of running is insufficient, excessive, or just right?

Knowing how much to run when coming back from injury can be a confusing and frustrating process. Photo: iRunFar/Eszter Horanyi

The stoplight system we discuss in this article is a contextualized guide that accounts for symptom responses throughout the day — during the run, post-run, the rest of the day, and even the next day — and is a better approach for crafting a tailored return to running with minimal setbacks.

Why Run-Walk and Pain Guides Fall Short

Let’s first explore why conventional running plans and pain management approaches often fail. Orthopedic medicine’s two most common strategies for returning to running include run-walk progressions and “let pain be your guide” approaches.

Even when combined, the two strategies are incomplete and problematic, often leaving individual runners struggling to run pain-free again.

Using pain while running as your only indicator can lead to slower or incomplete recovery. Photo: iRunFar/Eszter Horanyi

First, many run-walk progression programs are rigid, arbitrary one-size-fits-few protocols that fail to account for an individual’s specific injury status, pain levels, biomechanical efficiency, or overall health. They also fail to take into account an individual’s pain response to load application.

Second, the old adage of “let pain be your guide” is also problematic and often leads runners astray, frequently directing them to run too little or too much.

There are many different types of pain that indicate different things. Pain is complicated and can’t always be classified as good or bad:

- Sharp pain isn’t necessarily bad, but dull, low-level pain isn’t necessarily good

- Pain during runs isn’t necessarily bad, but pain-free runs aren’t necessarily good — especially if pain is worse post-run and the rest of the day

- Pain is often a necessary part of remodeling healing tissue

Benefits of the Stoplight System

The stoplight system is data-based and offers a structured yet adaptable framework for runners based on their individual response to tissue loading. By assessing symptoms before, during, and after activity — extending to the full 24-hour period surrounding a run — this approach guides decisions on whether to maintain, reduce, or pause running volume.

Individual Context Is King

The stoplight system is contextual, accounting for each individual’s entire day-in-the-life and their unique demands.

For example, an office worker may have a swifter recovery from plantar fasciitis than a service industry professional who must stand and walk all day. But that same office worker might progress more slowly with a low back injury if they are forced to sit most of the day.

Individuals can have different recovery times based on their unique bodies and life circumstances. Photo: iRunFar/Eszter Horanyi

General Trends Over Brief Spikes

Individual data points of pain coming from a single run can be misleading, and a stoplight system provides a much larger data set for a person over the course of a whole day.

A runner might experience a few or even several sharp, stabbing, and severe pains during a run. If those pains are extremely short — a second or less — and the rest of the run is pain-free, and they have no other symptoms the rest of the day, even those intense pains are, at worst, anomalous, and at best, part of the tissue remodeling process.

Conversely, a pain-free run but increased soreness, stiffness, and discomfort the entire rest of the day is nearly always indicative of tissue overload.

The Stoplight System for Returning to Running

The stoplight system provides guidance based on individual systems throughout a 24-hour period and during key parts of the day: during the run, post-run, the rest of that day, and the following morning. The totality of symptom response provides the best guide for tissue integrity, including how it accepted the training load, and its capacity to accept more load.

The stoplight system can help you adjust your running volume based on indicators over a 24-hour period. Photo: iRunFar/Eszter Horanyi

The system outlined below provides guidance on running progression based on symptoms during the day, with indications for how to adjust running based on symptom feedback:

Green Light: This indicates minimal symptoms, suggesting the body is tolerating the current load effectively.

- During the run: Symptoms are absent or minimal. Early discomfort, if present, resolves quickly. Brief, sharp sensations that dissipate rapidly are acceptable, provided no compensatory patterns (e.g., limping) emerge.

- Post-run: Mild soreness or stiffness may occur but resolves within an hour, returning to baseline function.

- Next 24 hours: No symptoms persist through the day. Minimal to no discomfort the next morning.

- Indications: Repeat the same running volume the next day. A key metric of progress is consecutive days of running without symptom escalation, reflecting improving tissue integrity.

Yellow Light: This signals caution, with mild symptoms indicating the need for careful management.

- During the run: Mild to moderate symptoms arise but do not lead to compensatory movements. Early discomfort that lessens during the run is tolerable.

- Post-run: Mild soreness or stiffness occurs but dissipates within an hour. No significant swelling or prolonged discomfort is present.

- Next 24 hours: Mild soreness or stiffness may appear later in the day or the following morning, but remains manageable.

- Indications: Take one day off from running, opting for non-impact cross training like cycling or swimming. The next running session should maintain the same volume or reduce it by 10% to 20% to avoid overloading.

Red Light: This demands an immediate halt, as symptoms indicate excessive stress on healing tissue.

- During the run: Persistent or worsening symptoms emerge, particularly if they appear mid-run or fail to subside. Compensatory patterns are present.

- Post-run: Notable stiffness or soreness persists beyond an hour, indicating overstress.

- Next 24 hours: Symptoms linger through the afternoon, evening, or into the next morning with moderate to significant discomfort.

- Indications: Cease running and all impact activities until non-running symptoms return to minimal levels. Focus on non-impact cross training, such as pool running or elliptical training, to maintain fitness without aggravating the injury.

Key Concepts for Effective Recovery

Using pain as a guide in the return to running is critical, but it’s not as simple as considering all pain during a run bad or a pain-free run good.

Pain during a run is not necessarily negative. Provided it resolves post-run and remains minimal throughout the day, pain during a run can be ok! This often reflects tissue remodeling, a natural part of healing where controlled stress fosters adaptation.

A pain-free run is not necessarily positive if pain is worse afterward. A pain-free run followed by significant post-run or next-day discomfort suggests activity-based desensitization, where irritable tissue “loosens up,” temporarily masking symptoms during activity, only to flare later. This is very common with tendinopathy and joint pain. If pain is worse the rest of the day and the next day, this indication warrants a red-light response, regardless of how good the run felt.

Watch the market trends. Adopt a long-term perspective to recovery, akin to tracking stock market trends. Avoid fixating on a single moment — a good or bad run — and instead evaluate the entire 24-hour cycle. Ask if today was an improvement over yesterday. This broader view is the best measure of healing tissue integrity and is a superior guide for smart activity progression.

Positive Progression

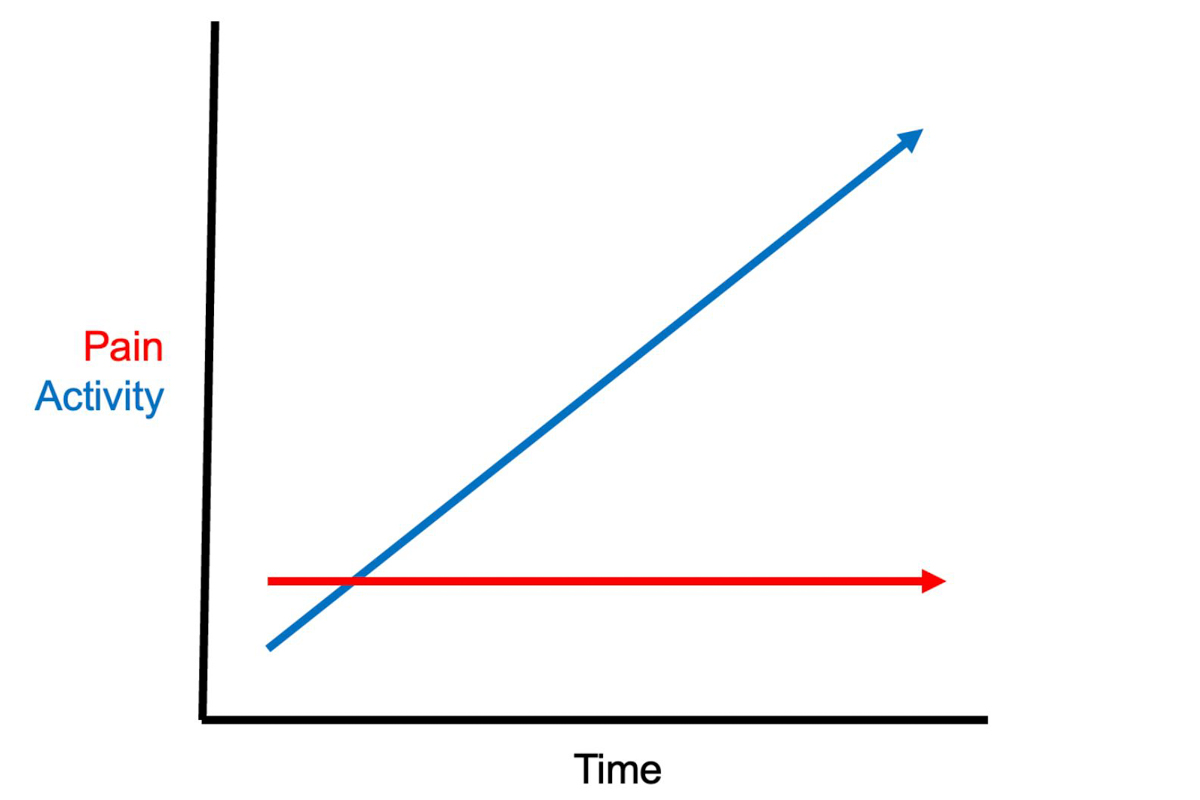

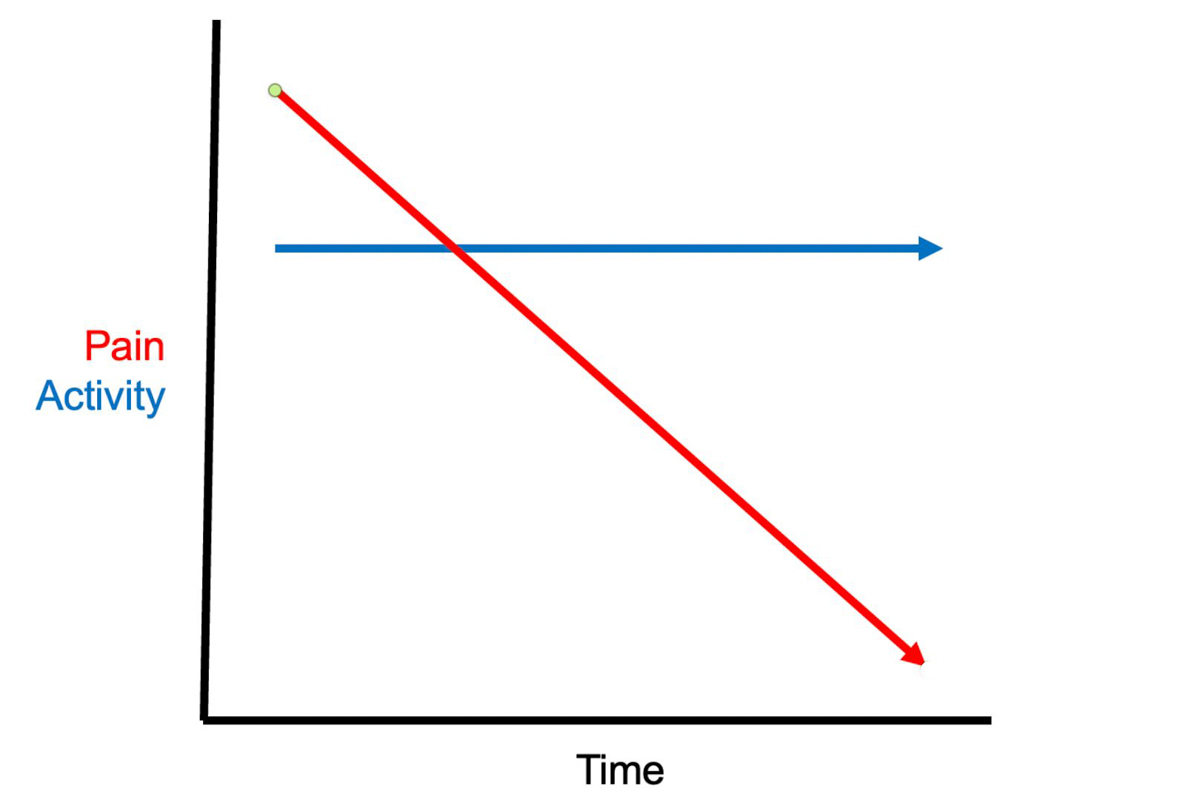

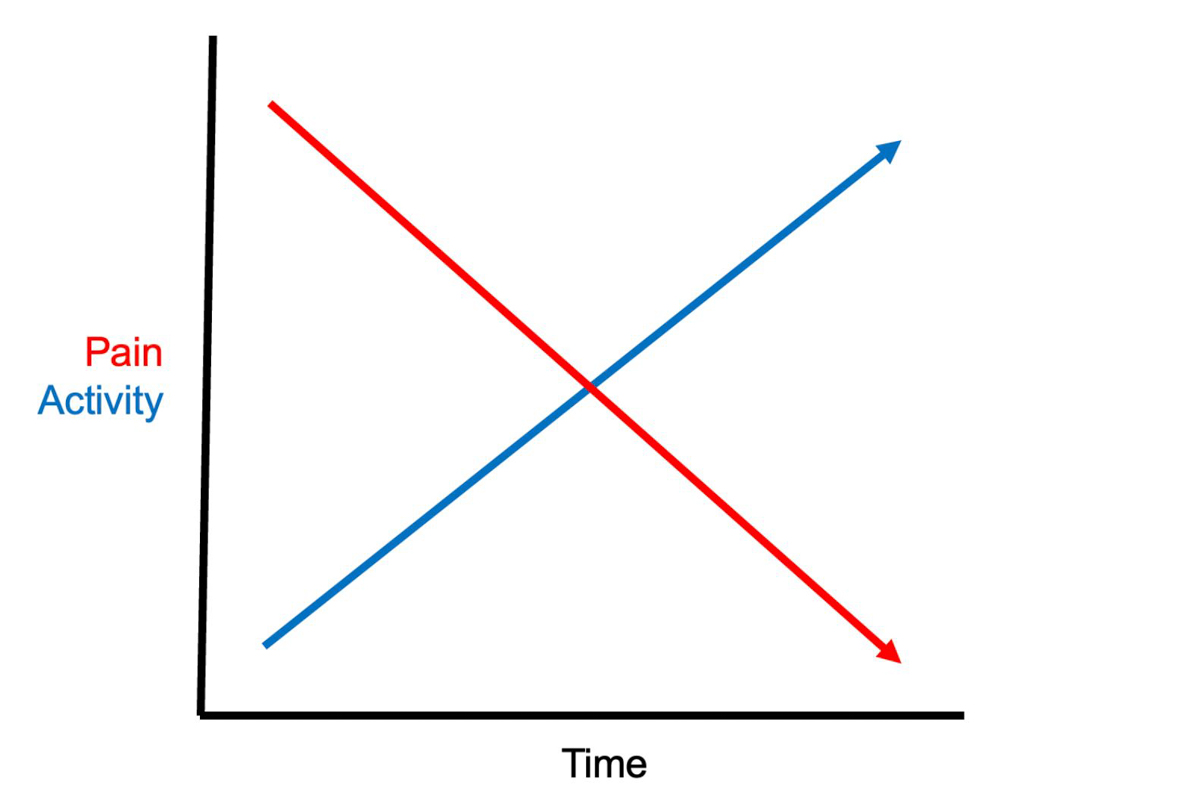

When returning to running, people crave the idyllic, full-running, no-pain outcome. As if there are two levers, ailing runners want their pain switched to zero and their running switched to full.

Pain decreases as activity level increases. This rarely occurs when returning to running from injury.

Yet it seldom, if ever, works that way. Instead, improved tissue integrity has two other forms:

More running volume, same mild to moderate symptoms. In this case, symptoms remain consistently mild while day-to-day running volume increases. In this case, the pain is often due to remodeling tissue. A runner can feel mildly sore while running or briefly thereafter. With time, increased load with low-level pain often leads to the second category described below.

Same running volume, fewer symptoms. Once tissue load has increased to moderate levels, consistent running volume results in improved tissue integrity and decreasing pain.

Both scenarios represent positive progressions that, given enough time and consistency, can lead to a full return to running, pain-free. Consecutive green light days, where load is tolerated without setbacks, signal growing resilience.

Conclusion

This stoplight system empowers runners to navigate recovery with precision, moving beyond rigid programs to a responsive, symptom-guided approach. By tracking symptoms across the full day, runners can optimize load, minimize setbacks, and build confidence in their return. Stay disciplined, listen to your body, and trust the process to guide you back to the trails.

Call for Comments

- Have you used a stoplight-style system to return to running after an injury? Did it work for you?

- What setbacks have you encountered while returning to running after an injury?