“Well, it looks like we might already be lost.”

Our vehicle was still in sight, even through the dense morning fog, and we already couldn’t find the trail. We were at the Crystal Creek Trailhead, which is nearly an hour’s drive from Jackson, Wyoming — a fairly obscure place to start a long trail run. Even though I spent hours meticulously planning this route, the lack of a basic trail sign left Luke Nelson, Steven Gnam, and me wandering in the misty morning light just trying to find a path into the Gros Ventre Wilderness.

The Gros Ventre Wilderness (pronounced “gro vahnt”) of Wyoming is an often overlooked, yet spectacular, wilderness area nestled between the can’t-miss-it obvious beauty of Grand Teton National Park and the Wind River Range, not to mention it is also tucked nicely in the shadow of Yellowstone National Park as well. My friends and I affectionately joke that it should actually be called “The Gros Ventre Bear Vortex,” as the landscape is prime grizzly bear habitat that is literally surrounded by other ideal grizzly bear habitats. It is not surprising that the Gros Ventre Wilderness, part of the Bridger-Teton National Forest, has a reputation for being unusually quiet, from a people perspective, that is.

Solitude Monitoring in the Gros Ventre Wilderness

Earlier in September, I planned a two-day run that would take us on a wild loop through the heart of the Gros Ventre Wilderness, not to set any sort of speed record or to be the first to do some obscure route, but with the simple goal of what’s called solitude monitoring. Since January 2025, when the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) was created, federal agencies like the United States Forest Service have been reeling from budget and staffing cuts. Prior to the DOGE cuts, there were three wilderness rangers tasked with patrolling the Gros Ventre Wilderness and were key resources for the Bridger-Teton National Forest’s management of the area. Wilderness rangers are the eagle eyes and worn, weathered hands of the U.S. Forest Service as they patrol trails on foot to enforce Leave No Trace principles, educate visitors on regulations, and collect field data. They are a key resource for wilderness preservation. Presently, 13 of Wyoming’s 15 wilderness areas do not have designated rangers, including the Gros Ventre.

The Gros Ventre Wilderness of Wyoming provides an outstanding solitude experience. Photo: Steven Gnam

Another lesser-known job of wilderness rangers is indeed solitude monitoring. Opportunity for solitude is one of four defining wilderness characteristics identified in the 1964 Wilderness Act. In fact, the U.S. Forest Service even has a National Minimum Protocol for Monitoring Opportunities for Solitude. The Wyoming Wilderness Association (WWA), a non-profit organization, began a partnership with the Bridger-Teton National Forest in 2020 to engage visitors in environmental stewardship through their solitude monitoring program. The program was meant to supplement the work of the U.S. Forest Service, but after the DOGE cuts, this data collection and management requirement has fallen to WWA alone. Even though monitoring solitude does not guarantee the preservation of wilderness character, it certainly informs and helps improve wilderness stewardship and management.

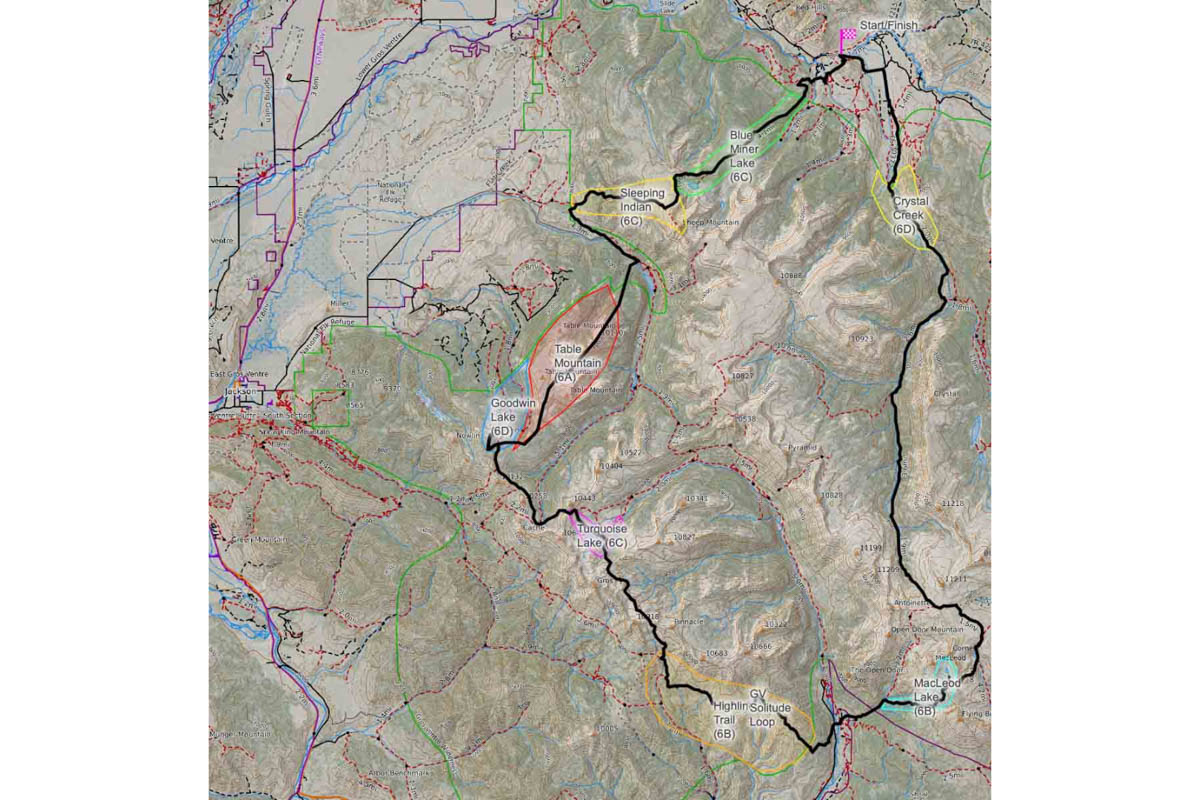

Luke and I were starting this big adventure run at the Crystal Creek Trailhead because that was one of eight solitude monitoring zones that have been targeted for data collection. The very specific running route that I created connected all eight solitude monitoring zones into one big, beautiful loop. For two days, we ran, hiked, and scrambled over just about every type of mountain terrain possible and traveled late into the night deep in country where we were not the apex predators.

Finding Solitude

So what did we find out there? Well, we certainly had a full-on solitude experience of our own. In the Crystal Creek solitude zone, we saw two backpackers warming themselves up with a steaming cup of coffee, and those were the last people we would see in the backcountry for the next 50 miles. As we worked our way deeper into the Gros Ventre, there were little to no signs of humans. We followed nearly a continuous path of fresh wolf prints and saw zero boot prints.

After cresting the divide between Gros Creek and Shoal Creek, we attempted an off-trail route up and over a narrow ridge that would drop us into the MacLeod Lake solitude zone. My good friend and former Gros Ventre Wilderness Ranger, Peggie dePasquale, shared route beta with me before the trip, saying, “I think that route probably goes … maybe.” Peggie knows and loves the Gros Ventre perhaps more than anyone and was a victim of the recent DOGE cuts, though she’s now joined the Wyoming Wilderness Association. U.S. Forest Service employees like Peggie are unsung heroes of wilderness preservation, typically doing work that nobody sees but everyone appreciates. As it turns out, Peggie’s route into MacLeod Lake did go, even if we did climb up alarmingly unsettled boulder fields that lacked any lichens — meaning the boulders have not been stationary long enough for them to grow — and a spicy but fun scree ski down in the solitude zone. An unmaintained trail is the standard route to the spectacular MacLeod Lake cirque, and the only sign of people we saw was a lone set of boot prints.

A Night at Turquoise Lake

Have you ever smelled a bear before you saw it? As we hiked and ran our way up into the next solitude zone, the Highline Trail, we got whiffs of the sour and rank smell associated with the big bruins of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. While we never actually bumped into a grizzly bear, we certainly sensed their presence out there. The Highline Trail is an area that has a reputation for being a maze of paths and trails, and it appears to have as much bear traffic as people traffic. We had to bring our A-game for navigation and map reading as we worked our way across unmaintained trails and passed through intersections that only had a stump of a signpost left. The wildflowers were taller than me — which I suppose isn’t saying much — and the evening light shone a warm glow on everything as we wove our way in and out of subalpine meadows.

We once again took an obscure off-trail route over a high pass to shortcut our way to the final solitude zone of the day, Turquoise Lake. I always look for elk paths to show me the way in terrain like this, and those master navigators haven’t let me down yet. We reached the crest of the pass just as the sun well and truly dipped below the horizon, and the wind started to really have a cold bite to it. We all called home to our wives, layered up, and began rock hopping our way through old moraines and damp alpine basins. Flickers of lightning at least 100 miles away looked like far-off fireworks on the Fourth of July — a fitting celebration to America and the public lands we were enjoying.

The Turquoise Lake zone was an important destination for us, and our predetermined bivy spot. One aspect of the Solitude Monitoring Protocol is that monitors must spend a minimum of four hours in a single zone before submitting an official report. This is often difficult to do for trail runners as we pass through these areas too quickly. Luke and I generally spent two to three hours traveling through other zones, but we made sure to spend the required four hours at Turquoise Lake. We pulled on our puffy coats and settled into four-ounce bivy sacks to stay warm while our freeze-dried meals rehydrated.

Several times, our sleepy eyes and heads popped up in full alert as we heard a loud slapping sound that sounded like a basketball-sized rock being hucked off a cliff into the water. As it turns out, the local trout population leaps out of the water for a post-midnight meal, smacking the water as they fall back down. While outstandingly beautiful, Turquoise Lake was more impacted by humans than any of the other remote locations we visited. I packed out several garbage wrappers, and noted four fire rings all in close vicinity to the lake, which is more than I expected.

Back to Civilization

After packing up our tidy little camp, Luke and I skirted through the Goodwin Lake solitude zone, where again we saw more signs of elk than people, and then onto the Table Mountain solitude zone. I was especially fascinated by this area as it felt so under the radar. Viewed from a distance, Table Mountain is rather unnoticeable compared to the rest of the craggy Gros Ventre peaks and the towering Tetons, plus there are no maintained trails anywhere on the mountain. In reality, Table Mountain is a labyrinth of steep limestone cliffs and caves with unbelievable panoramic views of the entire Jackson Hole area. Signs of grizzly bear and elk abound, and good off-trail travel skills are helpful for crossing the high plateau.

Luke Nelson putting his ski patrol skills to use on a scree slope above MacLeod Lake. Photo: iRunFar/Gabe Joyes

The final two solitude monitoring zones were Sleeping Indian — otherwise known as Sheep Mountain — and Blue Miner Lake. The Sleeping Indian solitude zone is adjacent to the town of Jackson and the National Elk Refuge, so visitation here is understandably much higher. We crossed paths with several sets of hikers on this beautiful and warm early September afternoon. Crossing over to the other side of Sleeping Indian Mountain into the Blue Miner Lake solitude zone was a complete transformation — trails were sparse again and at times difficult to follow. Grizzly bear scat full of freshly digested berry pits was a common sight. Water was sparse, and Luke and I were thrilled to find several massive semi-permanent snowfields that had carved their way into north-facing slopes, protected from harsh sun rays. After topping off our bottles and filling up our bellies — Gros Ventre literally translates from French to “big belly” — we embraced the long descent to the Gros Ventre River valley, where our adventure had initially begun.

After 65 miles and nearly 20,000 feet of climbing, Luke and I had completed our goal of visiting all eight solitude monitoring zones and completed a Solitude Monitoring Field Tracker that we could submit to the Wyoming Wilderness Association and the Bridger-Teton National Forest.

Future of Solitude Monitoring

I loved this adventure and the memories will stick with me forever, but it did leave me with an uneasy feeling and so much to contemplate about the future of public lands. My gut feeling was that supporting the U.S. Forest Service as a volunteer is an important part of being a public land user, but it felt off to be out there doing our part when the government is not doing theirs. People like my friend, Peggie, who have dedicated their professional careers to being stewards of these landscapes, have been cast aside in the spirit of “cutting bureaucratic excess, saving taxpayer dollars, and preventing runaway government waste.” My personal opinion is that the federal government maintaining federal lands as written into law is not runaway waste, but the right thing to do.

The Gros Ventre Wilderness no longer has any wilderness rangers to patrol it. Photo: iRunFar/Gabe Joyes

At one point during the run, Luke posed the question to me, “Who helps the helpers, Gabe?” I personally will plan on at least another solitude monitoring trip next summer, and will dutifully submit my findings to the U.S. Forest Service once again. If you are interested in helping public land managers in your own local area, or want to support the U.S. Forest Service’s National Minimum Protocol for Monitoring Opportunities for Solitude, check out resources like the Wyoming Wilderness Association or The Wilderness Society to find out what needs there are in your neck of the woods, or visit Patagonia Action Works to connect with local environmental groups. You can also report how federal layoffs have affected your experiences on public lands through the Wyoming Outdoor Council’s Public Lands Hotline.

Lastly, if you have ever been filled with a sense of awe by a big, beautiful — and roadless — landscape, consider submitting a comment to Secretary of Agriculture Brooke L. Rollins before September 19, 2025, to encourage the federal government not to rescind the 2001 Roadless Area Conservation Rule and to keep our precious public lands as wild as possible.

Finding lingering snowfields on north-facing slopes in the Gros Ventre Wilderness. Photo: iRunFar/Gabe Joyes

Call for Comments

- How important is it for you to have regular solitude experiences in your life?

- How have you been able to give back to your public lands?