[Editor’s Note: On November 7, 2025, Michelino Sunseri received a presidential pardon from President Donald Trump.]

Just over a year ago, on September 2, 2024, Michelino Sunseri, now a 33-year-old professional trail runner, tagged the summit of Wyoming’s Grand Teton and returned to the trailhead in 2 hours, 50 minutes, and 8 seconds, faster than the long-standing fastest known time (FKT) held by Andy Anderson since 2012.

But while the clock said Sunseri was faster, a controversy kicked in almost immediately, landing him in federal court. Now, exactly a year after the incident, on September 2, 2025, he was found guilty of leaving an established trail and using a shortcut.

The controversy started on his descent from the Grand Teton, where Sunseri used a closed shortcut known as the “old climbers’ trail,” cutting a major switchback on the established trail. The shortcut, though historically used by mountaineers, was explicitly marked as closed for revegetation. Sunseri stepped past signage intended to protect sensitive terrain that would later become a critical flashpoint in the trial.

A few days later, the National Park Service (NPS), the government agency that administers the U.S.’s national parks, including Grand Teton National Park, where this took place, issued him a mandatory citation under 36 CFR 2.1(b), which prohibits shortcutting on federal trails. The charge was a Class B misdemeanor, punishable by up to six months in jail and a $5,000 fine.

What might seem like a minor infraction escalated into a full-blown federal trial, sparking heated debates in the trail running world, legal circles, and seemingly within the federal government itself as well. At stake wasn’t just a disputed FKT anymore, but broader questions about environmental ethics in outdoor sports, prosecutorial overreach, and whether using a historical climbers’ path should really be treated as a federal crime.

Now, in the wake of this trial’s verdict, this article explores the case that could have implications far beyond a single switchback.

The Grand Teton is the tallest point of the Teton Range in Wyoming and Idaho. Here, it’s photographed in the background, with the shorter and less technical Middle Teton in front. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

The Grand Teton FKT Route and the Shortcut

The Grand Teton FKT route is roughly 13 miles round trip and has nearly 7,000 feet of vertical gain as it travels to and from the tallest point of the Teton Range, which hugs the border of Wyoming and Idaho. The route involves miles of maintained singletrack trail lacing through forests, meadows, and scree fields before yielding to scrambling and alpine climbing before reaching the 13,775-foot summit. Its profile and prestige have long made it a sought-after FKT, including by high-profile athletes like Kilian Jornet, who held the record before Anderson.

For his record attempt, Sunseri followed the standard trail to the summit. But on the descent, he veered onto an unmaintained path known locally as the old climbers’ trail. At its upper entrance, the shortcut is marked with a sign that reads “shortcutting causes erosion.” At its base, another sign reads “closed for regrowth.” The detour cuts off roughly half a mile of trail, though Sunseri had trained on the longer, official route in the lead-up to his attempt.

According to Max Mogren, a local citizen activist and social media personality based in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, where the trial took place, many previous FKT holders used the same shortcut. “As far as I know, Michelino is the only person who has faced serious consequences for using that trail.”

While park officials maintained the trail is clearly closed and off-limits, they later acknowledged in court that it had been a common route in prior decades and had not undergone a public signage update or closure announcement in recent years.

Afterward, in a Strava post, Sunseri acknowledged that he had knowingly taken the closed shortcut and wrote, “I would 100% make the exact same choice” if he were to do it again.

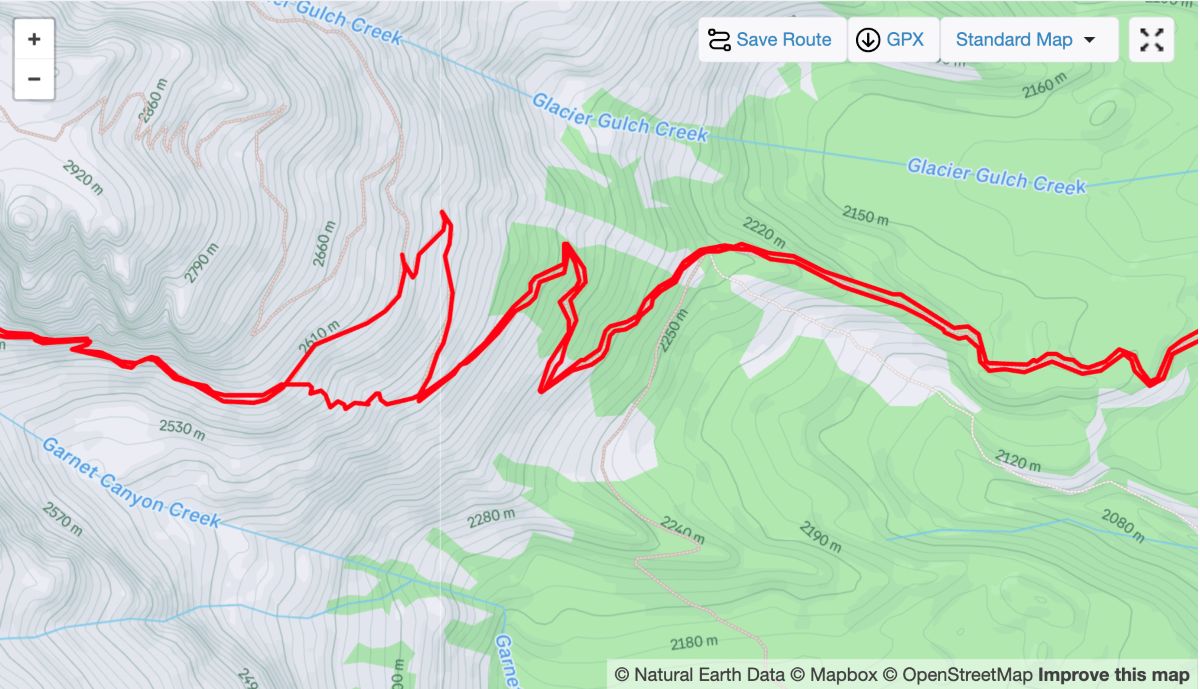

The map from Sunseri’s Strava, showing the route he took to cut the switchback in question. Image is a screenshot from Strava.

On September 3, 2024, one day after the attempt, law enforcement rangers at Grand Teton National Park began an internal review. On September 11, Sunseri contacted the park to offer clarification and volunteered to help with signage or trail restoration. Instead, he was invited to a formal meeting. During a phone call on September 24 with Jenny Lake District Ranger Chris Bellino, he was informed that he would be issued a mandatory citation, a legal notice requiring a court appearance, and that charges would be filed.

By September 18, the official FKT record-keeping website, FKT.com, had rejected Sunseri’s attempt. In a statement to iRunFar, site editor Allison Mercer said, “Based on our conversation with the NPS and in accordance with our own guidelines, we have decided to reject Sunseri’s submission. We don’t condone anything that is against the law.”

An extract from Sunseri’s Strava post where he talks about the decision to cut the switchback. Image is a screenshot from Strava.

The Trial

Sunseri was charged with violating 36 CFR 2.1(b), a federal regulation prohibiting shortcutting on designated trails, and tried in U.S. District Court for the District of Wyoming. The trial began on May 20, 2025, and continued into the following day. Following the trial, U.S. Magistrate Judge Stephanie Hambrick deliberated for over three months, delivering a guilty verdict on September 2. The verdict noted the judge’s sentence will come at a later date.

Michelino Sunseri outside the courthouse at his trial for cutting a switchback during his 2024 Grand Teton FKT attempt. Photo: Brad Boner

What was not in dispute was that Sunseri took the shortcut, or that legally, doing so violated a part of the Code of Federal Regulations governing national parks, which states, “Leaving a trail or walkway to shortcut between portions of the same trail or walkway … is prohibited.”

This regulation falls under Title 36 (Parks, Forests, and Public Property), Part 2 (Resource Protection, Public Use and Recreation), and is intended to prevent environmental degradation, such as erosion and habitat damage caused by off-trail travel in sensitive areas.

Additionally, the Grand Teton National Park Superintendent’s Compendium — compendia are documents unique to all national parks that apply the Code of Federal Regulations into park-specific rules — reinforces this regulation by prohibiting travel through any areas signed as closed for restoration or revegetation. The shortcut used by Sunseri was marked with such signage, making his use of the route a clear violation of both federal regulations and park-specific rules.

Thus, the controversy has centered more on whether the charges and potential punishment fit the offense. His defense team, led by Jackson-based attorney Edward Bushnell and joined by Harvard Law graduate Alex Rienzie, who had originally been documenting Sunseri’s FKT attempt as a filmmaker, has argued that the case exemplifies overcriminalization. They contend that Assistant U.S. Attorney Ariel Calmes, the attorney prosecuting the case, pursued disproportionately severe charges for a minor violation. That critique has been echoed by several legal observers and aligns with concerns raised in a May 9 Executive Order from the White House, which called for federal agencies to avoid unnecessary criminal penalties for regulatory infractions.

As mentioned, Sunseri had proactively contacted the park on September 11, 2024, offering to help close the trail or assist with signage. Those offers were declined, and instead, in early 2025, prosecutors offered a deferred prosecution deal, but with severe terms, including 1,000 hours of community service, reeducation classes, and a five-year ban from Grand Teton National Park.

Behind the charges is the fact that Sunseri’s public status and social media influenced the decision to press charges, as testified in court by Bellino and Grand Teton National Park Climbing Ranger Michelle Altizer, acknowledging that the NPS felt compelled to act due to the potential for others to follow Sunseri’s example. “We needed to send a message,” said Bellino from the stand.

Post-trial, documents obtained by the defense team via a Freedom of Information Act request made public, seemingly show internal division within the federal government on the degree to which this incident should be prosecuted. On May 19, the day before the trial began, Frank Lands, NPS operations deputy director stationed in Washington, D.C., sent an email to the case’s lawyers, Grand Teton National Park officials, and others stating, “We believe that the previously offered punishment, a five-year ban and fine, is an overcriminalization based on the gravity of the offense. Therefore, we withdraw our support.” However, the case had long been in the hands of the United States District Attorney’s Office, which operates in a different branch of government and has the legal authority to pursue cases it deems in breach of federal law, chose to go ahead with the trial.

Local mountain runner Kelly Halpin (right) and Michelino Sunseri (back to the photographer) speak outside the courthouse in Jackson, Wyoming. Halpin was subpoenaed by the prosecution and testified in court. Photo: Brad Boner

The case has drawn national attention. Legal experts, including those from the Cato Institute, a legal think tank, and the House Judiciary Committee, the standing U.S. House of Representatives committee charged with overseeing federal courts, flagged it as an example of overcriminalization of minor regulatory infractions. Stanford University law professor David Sklansky, who specializes in policing, prosecution, and criminal law, contextualized the case by saying, “This isn’t unprecedented, but it does reflect a choice to use criminal prosecution as a tool of public messaging.”

According to Sklansky, NPS officials are likely to weigh several factors when deciding to file federal charges, including any damage done or expenses incurred during the violation, how flagrant the violation was, and how much notice the defendant had of the rules. Said Sklansky, “Another factor that federal authorities may take into account in some cases, including, possibly, this one, is how well publicized the violation was.”

According to Mogren and others at the trial, park presence verged on excessive, with 16 federal employees present in person and three more via Zoom. “It would take one ranger with a shovel half a day to improve signage, but instead, 19 federal employees showed up to prosecute a runner,” said Mogren.

Will Rice, an Assistant Professor of Outdoor Recreation and Wildland Management at the University of Montana, has been following the case and indicated that the citation didn’t seem that far outside of the ordinary.

For instance, in 2024, movie star Pierce Brosnan was fined $500 and ordered to donate $1,000 to a Yellowstone area nonprofit for stepping off a trail in a delicate thermal area. Like in Sunseri’s case, Brosnan’s celebrity profile appeared to elevate the incident beyond routine enforcement, signaling a broader warning to the public. Similarly, in 2019, members of the Canadian influencer group “High on Life” were charged with federal misdemeanors after they posted videos of themselves walking off boardwalks in Yellowstone’s Grand Prismatic Spring area, biking in federally designated wilderness in Death Valley National Park, and filming commercial content without a permit in multiple national parks. Several members pled guilty and were fined, as the NPS made clear it was using the case to discourage influencers from creating content in ways that damaged protected landscapes.

“I do recall instances where visitors have been cited in recent years in Yellowstone National Park for leaving boardwalks in thermal areas. Additionally, it might be important to note that last year, a high-profile instance of a visitor hiking off-trail resulted in a grizzly attack in Grand Teton National Park,” said Rice. “Often, we think of Leave No Trace in the instance of hiking off-trail in popular destinations as being merely about not trampling vegetation and causing erosion, but it can also lead to negative impacts on wildlife, as research shows that wildlife often avoid buffers around heavily used trails.”

Sunseri’s defense team’s strategy has revolved heavily around the argument that the NPS failed to warn trail users and enforce trail closures sufficiently, and that it singled Sunseri out among previous record holders who had taken the shortcut, including Jornet’s 2012 record, which has since been flagged by FKT.com. Recently, the site divided up past records set using the “historic” and “modern” routes, those which cut switchbacks and those that stayed on designated trails, respectively, noting that it won’t accept records set using shortcuts.

The Grand Teton as viewed from one of the main roads in Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

Notably, Sunseri did not take the stand for his defense at the trial, and his team has also raised due process arguments, arguing in court that the signage was ambiguous and that the closure lacked formal notice under law, pointing out that the trail was not marked with criminal language, only a sign saying “Shortcutting causes erosion.”

“This story highlights the importance of signage in our national parks,” said Rice. “Research shows that signage can be very effective at keeping visitors on trail, but in this particular instance, it appears that the runner saw the signage and simply ignored it,” said Rice. “In this particular moment, we all need to read and obey signs and follow rangers’ direction more than ever, as our parks experience reduced staffing levels and increasing visitation.”

He notes that trail runners often approach the landscape with a different mindset than hikers, seeking efficiency over experience, which can heighten conflicts on already stressed systems. He emphasized the need for runners to “do their very best to leave no trace by sticking to the trail and not cutting corners.” But, Rice also pointed out a notable inconsistency in how park trails are classified and managed.

“The most popular trail, albeit according to the count of AllTrails reviews, in all of Grand Teton National Park is not a ‘designated trail’ at all, but the Delta Lake Trail, which is a social trail extending from the very route in question here.” He added that the contrast between that trail’s popularity and the controversy surrounding Sunseri’s shortcut is “interesting to say the least.”

Athletes Taking the Stand and Speaking Out

During the trial, Bryce Thatcher and Galen Woelk, defense witnesses, testified that the trail had long been used by mountaineers and climbers and still appeared on GPS apps like Strava, CalTopo, and Gaia.

Mountain athlete Kelly Halpin was subpoenaed to the stand by the prosecution, where she testified that she had encouraged Sunseri not to take the shortcut for his attempt because of the high-profile nature of the FKT. From the stand, Halpin said, “Professional athletes set the standards for all those who follow.” While Halpin had previously taken the old climbers’ trail, as her connection to the peak and public profile grew, she stopped taking the shortcut and publicly advocated for others to avoid it, too.

“Never in my life did I think I was going to be in a federal trial talking about Strava segments. This whole thing has been blown way out of proportion,” said Halpin in a statement to iRunFar. “I believe in ethics, stewardship, and sportsmanship. I also believe that someone should be able to make a mistake and then be able to correct it.”

Kelly Halpin believes athletes have a responsibility to be stewards of public lands. Photos courtesy of Kelly Halpin.

Thatcher, a longtime mountaineer and former guide with decades of experience in the park, testified that there has long been ambiguity surrounding the so-called old climbers’ trail — the route Sunseri used on his descent. Thatcher, who set a prior Grand Teton FKT himself in 1983, said the trail was widely accepted among local climbers and guides at the time.

“Back then, that trail was used by everybody — the guides, the rangers, everyone,” Thatcher said. “There was a sign that said, ‘Shortcutting causes erosion,’ but taking the shortcut was almost a rite of passage. If you were in shape, kind of in the know, a local, there every week, you took that trail. Now, if you were carrying a big pack full of climbing gear, you’d take the longer trail that goes by the lakes and switchbacks up. But if we were going light and fast, we took that trail, up and down. The Exum Mountain Guides [the iconic longstanding local guide service] and the climbing rangers took it too.”

Some athletes, including Ryan Burke, a Jackson-based mountain athlete with several major records to his name, including the unsupported FKT for the Wind River High Route, have argued that Sunseri’s shortcut undermined the integrity of the FKT and has jeopardized the relationship between runners, rangers, and other trail users.

“In my mind, this incident has always been much more of an ethical issue than a legal one. Even if he wins his current legal battle, that doesn’t make his behavior on the mountain any more acceptable.”

Burke also worries that the broader legal battle and debate over overcriminalization have overshadowed the core ethical issue: cutting the switchback. He emphasizes the importance of calling out the misstep to ensure other athletes don’t follow in Sunseri’s footsteps.

“Any athlete who attempts after him would be forced to risk a huge fine in order to stay competitive,” wrote Burke in an essay shared with iRunFar. “Most people, including myself, can easily forgive someone who stumbles, but it’s hard for people to move on when no accountability has been taken.”

The trial and the debate it has ignited have been polarizing, and both Burke and Halpin noted that they received significant harassment after speaking out.

What This Case Means for the Future

At the time of this article’s publishing, Sunseri’s defense team has not made a statement in response to the ruling. However, during the trial, they were clear they’d appeal a guilty verdict — and take the case as far as necessary to challenge what they see as a dangerous legal precedent.

“This isn’t just a case,” said Franc Sunseri, Michelino’s brother, in a statement to iRunFar in May 2025. “It’s a reckoning. The United States versus Sunseri is the United States versus truth, versus courage, versus the trailblazers who refuse to kneel.”

The questions raised by the case reflect a larger cultural inflection point, one where elite athleticism, public land management, and social media-fueled visibility increasingly collide. As trail running evolves from a niche subculture into a global sport with professional contracts and widespread digital documentation, how will its norms align with the conservation values embedded in the places where it happens?

The case poses sharp questions about enforcement discretion and the weight of public visibility in prosecutorial decision-making. If two runners make the same infraction, but only one has a sponsorship deal and a viral Strava post, should the consequences differ? And how can athletes navigating these public spaces ensure that their pursuit of excellence doesn’t come at the expense of the very landscapes they and their sport depend on?

Rice already sees this tension playing out across the American West.

“This story highlights a growing issue in public lands where trails designed for hiking are seeing explosions in trail running use,” Rice said. “In my backyard of Missoula, Montana, trail running is now the most popular activity in the Rattlesnake Wilderness, dramatically outnumbering hiking, backpacking, and stock use. The motivations are often quite different. A trail runner may prioritize efficiency, while a hiker might embrace the meander. In a time of shrinking trail budgets, both groups need to leave no trace, avoid cutting corners, and be courteous stewards of shared space.”

Runners make their way up Mount Sentinel in 2022 for the Up for Air event in Missoula, Montana. Trail runners now outnumber hikers in the area. Photo: Anastasia Wilde

Already, it seems this trial may be affecting trail runner behavior in Grand Teton speed efforts. This August, mountain athletes Jazmine Lowther and Jane Maus both set women’s FKTs on the Grand Teton, and used the official trail in doing so.

For Thatcher, the case reflects how much the sport has changed since his own record-setting efforts in the 1980s.

“Michelino, I think he had pure intentions, just doing it for the joy,” said Thatcher. “But the sport as a whole has evolved. Now, there are sponsors, money, and livelihoods involved. And naturally, that brings more scrutiny.”

While Thatcher believes the case has been blown out of proportion, he hopes it can serve as a teachable moment for both athletes and land managers. “There should be clear signage,” he said. “And I hope people understand that when you go for something this high-profile, you need to do your research. That’s part of being a responsible athlete.”

Call for Comments

- Where do you weigh in on this story and the verdict?

- What responsibilities do you think trail runners have to natural landscapes and the regulations that govern them?

We acknowledge this is a sensitive topic, and we welcome discussion of this story in the comments section. Comments violating our comment policy, designed to foster constructive dialogue, will be removed. Thank you.