I was recently on a group run, tucked in with old and new friends, when the topic turned to menstruation and a runner’s recent triumph — getting their period back.

An uproar of support rang out, and then we turned to the one guy in the group to all jokingly apologize for the period talk. Instead of blushing or brushing it off, he told us about how he just had a similar experience with other runners the week before. No longer taboo or accidentally overheard, period talk is now routine trail talk!

This experience is part of the baseline cultural shift I hope that many of you are also experiencing as the menstrual cycle has come into the light as an influencer of endurance running performance. With its newfound attention, we are also getting more original research and literature reviews that are trying to discern the differences between myth, anecdotes, and objective metrics.

We hope this article serves as a reference for not only those who menstruate but any of you who have someone who menstruates in your life. In this article, we’ll cover what we know currently about menstruation, the hormones involved, the impact they may or may not have on performance, and what practical habits you can bring into the training and racing of you and your menstruating friends, athletes, and loved ones to optimize running performance as the days of one’s monthly cycle tick by.

Please note that we are not diving into the equally important topics of birth control and menopause as they relate to athletic performance. Both topics deserve their own standalone articles. Stay tuned!

What Is the Menstrual Cycle?

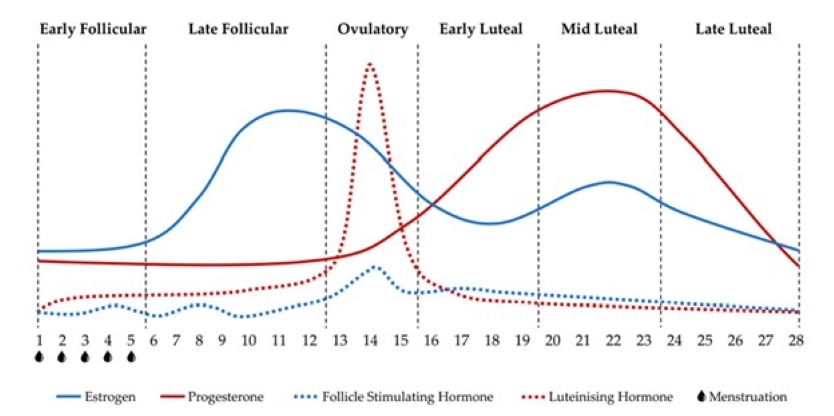

When you look at the menstrual cycle from the bigger picture perspective, it is a series of events with the goal of preparing the uterus for a potential pregnancy and is characterized by fluctuations in several sex hormones, including estrogen, progesterone, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone (1, 6).

These hormonal fluctuations encapsulate what is considered a normal or eumenorrheic menstrual cycle that lasts on average 20 to 35 days and is often expressed in the form of an idealized 28-day cycle.

The ebbs and flows of your circulating hormones further break the menstrual cycle into several phases: early follicular, late follicular, ovulatory, early luteal, mid-luteal, and late luteal.

The duration of each of these slightly varies from person to person and from cycle to cycle. You generally see this expressed as only two main phases, follicular and luteal, but the transition periods — where hormones start to rise or fall — likely have their own distinct physiological impacts and have not yet been fully explored (5). But more on that in a little bit.

Let’s talk phases, or at least what we know about them, broadly (1, 2).

Early Follicular Phase

This phase starts with menstruation, or when you start bleeding, and lasts for four to six days. Throughout this time estrogen, progesterone, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone are all low and stable.

Late Follicular Phase

During this phase, your pituitary gland makes follicle-stimulating hormone, telling your ovaries to prepare an egg for fertilization, and your estrogen starts to rise as the egg matures. As estrogen peaks, this triggers a rapid increase in the luteinizing hormone, which triggers ovulation.

The entirety of the follicular phase, the early and late follicular phases included, can last from 10 to 22 days.

Ovulatory Phase

This is the phase in which the egg is released from your ovarian follicle into the uterus. This phase lasts from 16 to 32 hours, and some individuals experience pain and cramping during this phase with the release of the egg.

Early Luteal Phase

The early luteal phase begins right after ovulation. The corpus luteum, a cyst that forms after ovulation within the ovary that eventually degrades on its own, forms and secretes progesterone and a small amount of estrogen.

Mid Luteal Phase

This phase contains the peak for progesterone and the second smaller peak for estrogen. During this phase, the lining of the uterus, called the endometrium, builds up in preparation for the implantation of a fertilized egg.

With pregnancy, the luteal phase ends here, and without pregnancy, the late luteal phase occurs.

Late Luteal Phase

In the late luteal phase, the egg remains unfertilized, and the corpus luteum degrades, which causes a slow decline in progesterone and estrogen. This decline in hormones causes the uterine lining to eventually detach and begins the menstrual cycle all over again with the shedding of that lining in the form of your period.

Encapsulated as one phase, the luteal phase lasts for 10 to 14 days.

This image demonstrates an idealized pattern of changing sex hormones and their corresponding phases (follicular, ovulatory, and luteal) over the course of a 28-day menstrual cycle, including progesterone, estrogen, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone. Image: Carmichael, M.A.; Thomson, R.L.; Moran, L.J.; Wycherley, T.P. The Impact of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Athletes’ Performance: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021,18, 1667. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041667 (1)

What If I Don’t Menstruate?

We should also note that not everyone who has a uterus menstruates. That might be because you are on a progesterone intrauterine device (IUD), which leaves you with less uterine lining to shed, or it might be because you are menopausal. There are a few other irregularities that you should be aware of, including oligomenorrhea, primary amenorrhea, and secondary amenorrhea (2).

Oligomenorrhea is an inconsistent or irregular period, which means less than six to eight periods per year, or a menstrual cycle that lasts longer than 35 days.

Primary amenorrhea is any individual who has not had their period by the age of 15.

Finally, secondary amenorrhea is one we see a lot in athletics due to relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S). Secondary amenorrhea occurs when an individual who normally has a regular menstrual cycle loses their period for more than three months, or when an individual who has an inconsistent cycle loses their period for more than six months.

Losing your period is not normal and consulting with your primary care physician or obstetrician-gynecologist is recommended.

How Do Menstrual Cycle Phases Impact Physiology?

While we highlighted the reproductive function of female sex hormones above, these hormones also have a significant impact on other tissues in the body not responsible for reproduction (3).

These functions include altering fluid regulation, cardiovascular response, muscular response, injury risk, thermoregulation, and metabolic response, thereby affecting components of sports performance (3).

While over 90% of female athletes report negative symptoms that correspond with their menstrual cycle (5), and most menstruating athletes feel there is a decrease in physical capacity over their menstrual cycle, Olympic medals have been won at every phase of the menstrual cycle (3). So where might the menstrual cycle impact physiology and therefore impact performance?

Muscular Strength

Initially, it wasn’t clear if menstrual phases had much impact on muscular strength because anaerobic efforts appear largely unaffected by phase compared to endurance efforts. However, power and strength are not the same thing.

A 2022 study (7) suggests that estrogen has a building effect on skeletal muscles, producing a greater growth response to resistance training. Additionally, it appears that maximal muscle strength is greater during the follicular phase and during ovulation than in the luteal phase.

What this means in practice is that recovery and rebuilding of muscle fibers occur more quickly during the follicular phase than the luteal phase, making the follicular phase a better time for resistance training to enhance muscular strength and mass (7). Interestingly, this seems to occur because estrogen maintains and improves the quality of muscle.

Ashley Erba doing strength training, which can work well during the follicular phase. Cat optional! Photo: Ashley Erba

Injury Risk

Fluctuations in estrogen and progesterone influence more than just reproductive tissues. They also influence musculoskeletal tissues such as muscles, tendons, and ligaments (2). Several studies have pointed to a greater risk of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury occurrence in the late follicular phase and into the ovulatory phase when estrogen concentrations are the highest — which is believed to increase ACL laxity (10).

A study published in 2021 (10) evaluating injury in elite soccer players further cemented this notion, finding that athletes were twice as likely to sustain an injury during the late follicular phase than the early follicular phase or luteal phase. But perhaps more interesting is that they found about 20% of all injuries, in their sample, occurred in the days when an athlete’s period was overdue (10).

This is interesting because it agrees with previous studies that suggest that individuals experiencing oligomenorrhea and amenorrhea are at heightened risk for sustaining an injury and it is something for athletes and coaches to be aware of (10).

Thermoregulation

During the luteal phase when your progesterone is elevated, you experience an increase in basal body temperature, or your body’s temperature at rest, which for short athletic performances can be performance-enhancing, because this improves muscle contractility and force production (2). However, that elevation in body temperature imposes greater thermoregulatory and cardiovascular strain as performances get longer.

During this phase, body temperature is consistently elevated pre- and post-exercise without any change in cooling mechanisms like sweat rate or skin temperature. This can become a performance limiter since it decreases your ability to adequately dissipate heat to cool yourself down during warm endurance races (8).

Dressing to stay cool can be particularly important during the luteal phase. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

Metabolism

Shifts in hormones cause changes in metabolism, all of which happen at the cellular level. For example, high progesterone during the luteal phase may decrease fat and protein metabolism and increase carbohydrate oxidation. Whereas high estrogen during the mid-follicular phase increases fat metabolism and decreases carbohydrate oxidation (2).

It seems that these effects might be more apparent at higher intensities, while rates of carbohydrate and fat oxidation remain similar at submaximal intensities (1).

Fluid Retention

Females are already at higher risk for conditions like hyponatremia, or low blood sodium, than their male counterparts due to body size, but hormones play an increased role here (2). During the follicular phase with higher estrogen, sodium absorption and water retention are more likely because estrogen acts on aldosterone, a hormone that stimulates the absorption of sodium by the kidneys (2). While during the luteal phase, sodium reabsorption at the kidneys can be impaired, impacting fluid balance and plasma volume because progesterone acts as a diuretic (2).

Psychological and Behavioral Symptoms

In the week before your period, during the late luteal phase, many individuals who menstruate report psychological and behavioral symptoms (9). These symptoms include fatigue, lethargy, poor coordination, poor concentration, increased worry, unusually stressed, easily frustrated, reduced motivation to train, disengaged, moody, agitated/irrational, reduced confidence, depressed, and increased crying (9).

This happens because the fall-off in estrogen and progesterone correspond with a drop in serotonin, a chemical that is responsible for helping to carry messages between nerve cells in the brain and throughout your body — playing a key role in body functions like mood, sleep, and more.

All of which I’m sitting here nodding along. We all know our sports performance relies on both our physical and psychological states.

Recovery

Sex hormones directly impact our sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system pathways. Recall that the sympathetic system is our fight-or-flight system, which controls things like cardiovascular response, whereas our parasympathetic system is our rest-and-digest system, which returns the body to a state of calm.

We see this play out when monitoring heart rate variability (HRV), which is the variation between heartbeats that gives us insight into how we are absorbing stress from training and life, as a means of gauging recovery.

What this looks like is during the follicular phase, HRV — and thus recovery or rather your ability to absorb training load — is increased, while during the late luteal phase, HRV decreases along with your ability to recover from training (6).

Kelly Wolf (left) and YiOu Wang recovering with an ice bath in the Alps. It is important to be mindful of recovery during the luteal phase, when the body’s natural ability to recover and absorb training is reduced. Photo courtesy of YiOu Wang.

Why Almost Every Article Is Inconclusive

While reading research papers and narrative reviews on all aspects of the menstrual cycle and athletic performance I was struck by one theme: so much of this is speculative.

Females still make up less than 40% of research participants and depending on the area of study, this number can be in the single digits. This is because females have long been seen as confounding variables or even “unreliable test subjects” — all due to their naturally circulating hormones.

So, when individuals who menstruate are utilized as study volunteers, researchers try to control that by only testing them during the early follicular phase when progesterone and estrogen are both low and stable. This might make it seem like more reliable data, but what it really does is paint an incomplete picture. This is only the tip of the iceberg, because when researchers do try to test menstruating individuals more thoroughly, they haven’t quite nailed how to accomplish it.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis that came out in 2020 (4), led by some of the best in the field, they classified most of the data evaluated as “low” quality due to a host of methodological issues. What they found throughout the papers was that despite the desire to understand how estrogen and progesterone throughout the menstrual cycle impact athletic performance, most studies didn’t utilize tools to accurately pinpoint the cycles of the participants.

This review evaluated 78 research papers for that analysis, and still couldn’t avoid confounding variables, leaving everyone with more questions than answers. They determined that despite the incredible rise of female participation in sport at all levels, the research lags behind and is hamstrung by nuances.

This understanding — or, ahem, lack of understanding — more than anything highlights the importance of taking a personalized approach to your individual response to your cycle, in order to aid in your own training and performance.

While there might not yet be randomized controlled research trials to support any specific interventions, track your cycle, and be aware of your own symptoms because simply being more aware of it and its associated symptoms makes them easier to manage and mitigate.

Takeaways on Sports and the Menstrual Cycle

- Talk about it! Talk about it with your health care providers, peers, children, teammates, parents, and athletes. Communication and education remove taboo. If you’re a coach, start a dialogue with your athletes who menstruate to help remove the stigma.

- Knowledge is power, so track your cycle and your athletic performance along with it. One of the biggest takeaways from the research is that a lot of individual variability exists. What this means in practice is that phase-specific recommendations won’t work for everyone. Track your cycle, even on a paper calendar, and look for trends in subjective (how you feel) and objective (the metrics by which you measure your training) performance metrics and adjust to your personal cycle. Simply being more aware of your cycle and associated symptoms makes them easier to manage and mitigate.

- Reframe the menstrual cycle. This goes for both the people who menstruate and the people who care about menstruating individuals! It’s easy to get trapped in the societal narrative around the negative and unwanted symptoms that come along with a menstrual cycle. This needs to be reframed to avoid creating and reinforcing this barrier. Educate to empower, not to limit.

- Consider ovulation testing and temperature taking. Know if you are having ovulatory cycles by utilizing ovulation urine strip tests. You can also do this by monitoring basal body temperature, as you will see a slight increase in basal body temperature during ovulation. Both of these will also help you best differentiate between your follicular and luteal phases with better accuracy.

- Understand that more research needs to be done. While there are many studies that have looked at objective physiological metrics and the menstrual cycle, many have methodological issues, including researching only during one phase, not tracking several cycles, small sample size, and mischaracterization of certain forms of birth control. The way we will get better information on menstruation and athletic performance is by elevating the standards under which this data is collected and increasing the overall volume of research dedicated to these topics.

Call for Comments

- Have you had any noteworthy experiences racing at different points on your cycle?

- Is there anything you find helps offset any negative effects on your performance?

References

- Carmichael, M.A.; Thomson, R.L.; Moran, L.J.; Wycherley, T.P. The Impact of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Athletes’ Performance: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021,18, 1667. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041667

- Hackney, A. Sex hormones, exercise, and women. Scientific and Clinical Aspects. Springer International Publishing. Switzerland 2017. eBook.

- Meignié, A., Duclos, M., Carling, C., Orhant, E., Provost, P., Toussaint, J.-F., & Antero, J. (2021). The effects of menstrual cycle phase on elite athlete performance: A critical and systematic review. Frontiers in Physiology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.654585

- McNulty, K.L., Elliott-Sale, K.J., Dolan, E. et al. The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med 50, 1813–1827 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01319-3

- Bruinvels, G., Hackney, A. C., & Pedlar, C. R. (2022). Menstrual cycle: The importance of both the phases and the transitions between phases on training and performance. Sports Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-022-01691-2

- Sims ST, Ware L, Capodilupo ER. Patterns of endogenous and exogenous ovarian hormone modulation on recovery metrics across the menstrual cycle. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2021;7:e001047. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2021-001047

- Kissow, J., Jacobsen, K. J., Gunnarsson, T. P., Jessen, S., & Hostrup, M. (2022). Effects of follicular and luteal phase-based menstrual cycle resistance training on muscle strength and mass. Sports Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-022-01679-y

- Giersch, G.E.W.; Charkoudian, N.; Stearns, R.L.; Casa, D.J. Fluid Balance and Hydration Considerations for Women: Review and Future Directions. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 253–261.

- Brown, N., Knight, C. J., & Forrest (née Whyte), L. J. (2020). Elite female athletes’ experiences and perceptions of the menstrual cycle on training and sport performance. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 31(1), 52–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13818

- Martin, D., Timmins, K., Cowie, C., Alty, J., Mehta, R., Tang, A., & Varley, I. (2021). Injury incidence across the menstrual cycle in international footballers.Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2021.616999