You’re tough enough, but you’re tired. You are so tired, I thought to myself.

In the fall of 2013, as I stared down the barrel at my Olympic biathlon dreams, my whole world tumbled down. I was exhausted and my performance showed it. I couldn’t remember the last time I felt fresh. Getting out of bed was impossible and yet I couldn’t sleep. I was developing what felt like chronic upper-respiratory-tract infections. Though one October day felt like my breaking point, I had likely broken over a year before due to the multiple, compounding factors of too much training, too little recovery, and long-term stress exposure. I had overtraining syndrome (OTS).

While my teammates marched into the Opening Ceremonies of the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia, I hung up my skis and rifle, and retired. It took me almost two years to feel fresh again.

I wish I could bottle up the OTS and what I learned in order to spare other athletes from learning the hard way, too. This article represents just that, my attempt to distill what is currently known about OTS. We will cover training stress, its positive and negative adaptations, and what the scientific community has learned over the past 10 years to better identify athletes with OTS.

Author Corrine Malcolm competing at the 2011 Biathlon European Championships in Ridnaun, Italy. Photo: Patrick Coffey

Training is a Continuum

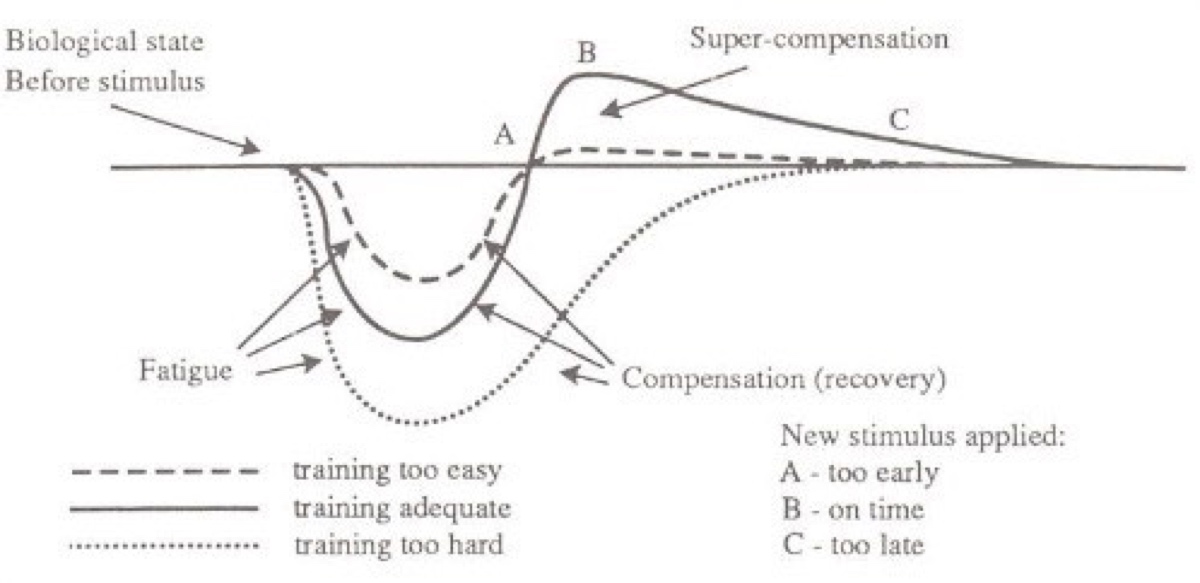

Effective training applies a training load that stimulates physiological change. This is accomplished via just-enough system overload paired with adequate recovery. Essentially, training involves walking up to the line drawn between too much and too little training over and over again, even stepping over it every once in a while, but always stepping far-enough back as well.

That sounds simple enough, but it’s actually kind of hard. Resting is not fun, our drive to accomplish our goals is fierce, and we tend to overlook outside stressors like work, school, family, and relationships (15). To add to the athlete’s confusion, the early phases of being under-recovered can leave us feeling out of shape and so we train harder when we really need to back off.

Training is a little bit like “Goldilocks and the Three Bears.” Too much training is too hard, not enough training means limited improvement, just enough training is ‘just right’ and we see ideal athletic improvement. Image courtesy of Adrenalinesf.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/supercompensation-curve_thumb.jpg.

Formerly considered burnout, staleness, chronic fatigue, and unexplained underperformance syndrome, OTS has been reported in 20 to 60% of elite athletes over the span of their career (16, 5) and is found in as much as 34% of the non-elite competitive population (5). However, it is believed that these numbers could be falsely high due to difficulties differentiating between the levels of maladaptation (adverse response) to training, or how far along the continuum between non-functional overreaching and overtraining syndrome an athlete might be.

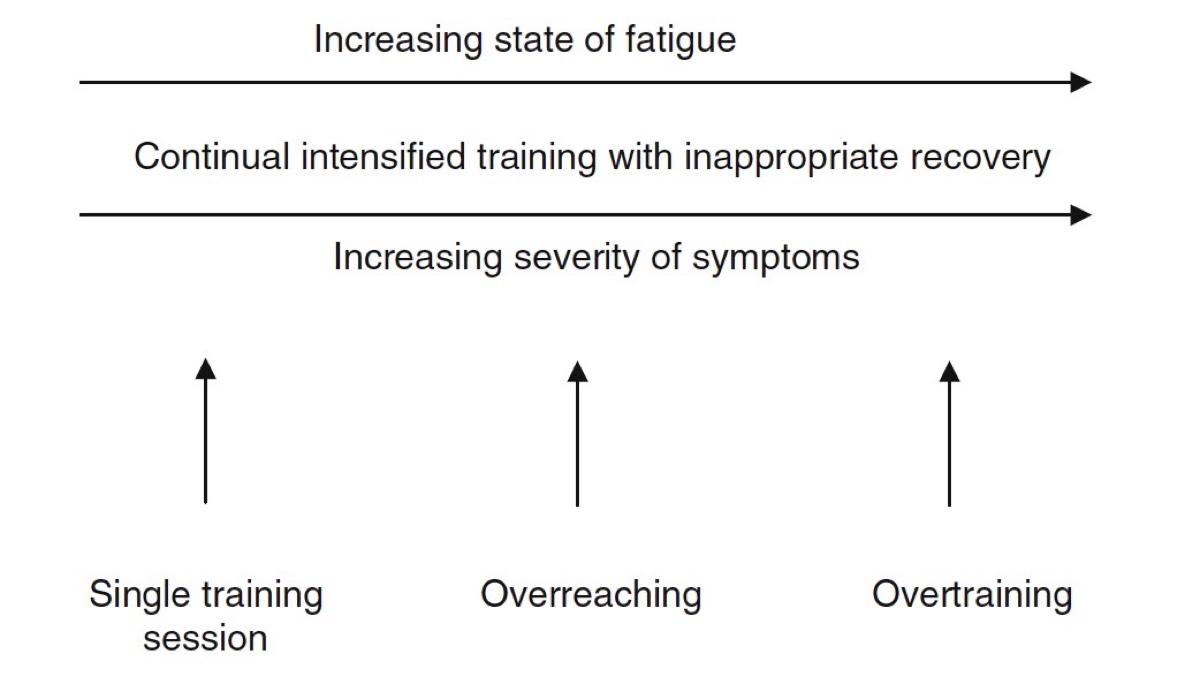

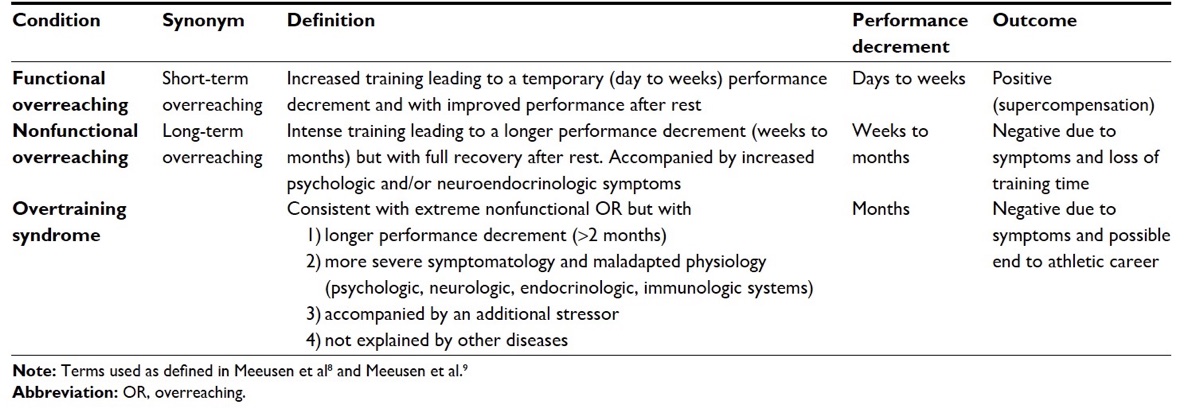

Perhaps the most important distinction of the last decade is the scientific community’s creation of common definitions for ‘overtraining,’ what is now broken into the two categories of overreaching and overtraining syndrome (OTS). Overreaching is a verb and it is something you actively do whereas overtraining syndrome is a noun describing the result of those actions, an outcome. OTS is a maladaptation to training; your body has an adverse response to the training stimuli and it results in various poor outcomes.

At this time, it is not known if OTS is more prevalent in male or female athletes (16). It is generally accepted that endurance athletes (cycling, running, rowing, swimming) who put their bodies under large quantities of stress for extended periods of time are at greater risk.

On the overtraining continuum, appropriate training progresses to (nonfunctional) overreaching and possibly to overtraining syndrome. That being said, even appropriate training has short-term negative symptoms. Image courtesy of Halson, S. L., & Jeukendrup, A. E. (2004). Does Overtraining Exist? Sports Medicine,34(14), 967-981. doi:10.2165/00007256-200434140-00003.

Many exercise physiologists look at an athlete’s training as a continuum of periodized stress over time. Generally, an athlete starts out intentionally but temporarily overloading the system, what’s called functional overreaching (FOR). FOR are moments when an athlete increases their training load (volume and/or intensity) and experiences a short-term performance decrease without any long-lasting, negative symptoms. When appropriate rest follows the temporary overload, typically a couple of days to two weeks (the latter in the case of a taper to a goal event), FOR leads to performance improvement. Train, rest, rinse, repeat.

However, when an athlete forgets to take their foot off the gas pedal, they may venture into non-functional overreaching (NFOR). Hone in on that name for me, non-functional means you no longer get benefits from this increased workload. In NFOR, an athlete experiences performance decrements, increased fatigue, and possibly hormonal disturbances. It takes much longer to return to homeostasis, and instead of getting that boost we are looking for after a couple days of recovery, we need three weeks to several months to recover and in that time we detrain.

Functional overreaching, non-functional overreaching, and overtraining syndrome described. Image courtesy of Kreher, J. (2016). Diagnosis and prevention of overtraining syndrome: An opinion on education strategies. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine,Volume 7, 115-122. doi:10.2147/oajsm.s91657.

How Do I Know I Have OTS?

What is the difference between NFOR and OTS? If an athlete keeps their foot on the gas pedal even more, they dig an even-deeper hole. For less severe cases of NFOR, an athlete simply taking two to three weeks off is generally enough to recover. However, if symptoms do not improve over that time or last for more than two months, you’re likely in OTS territory.

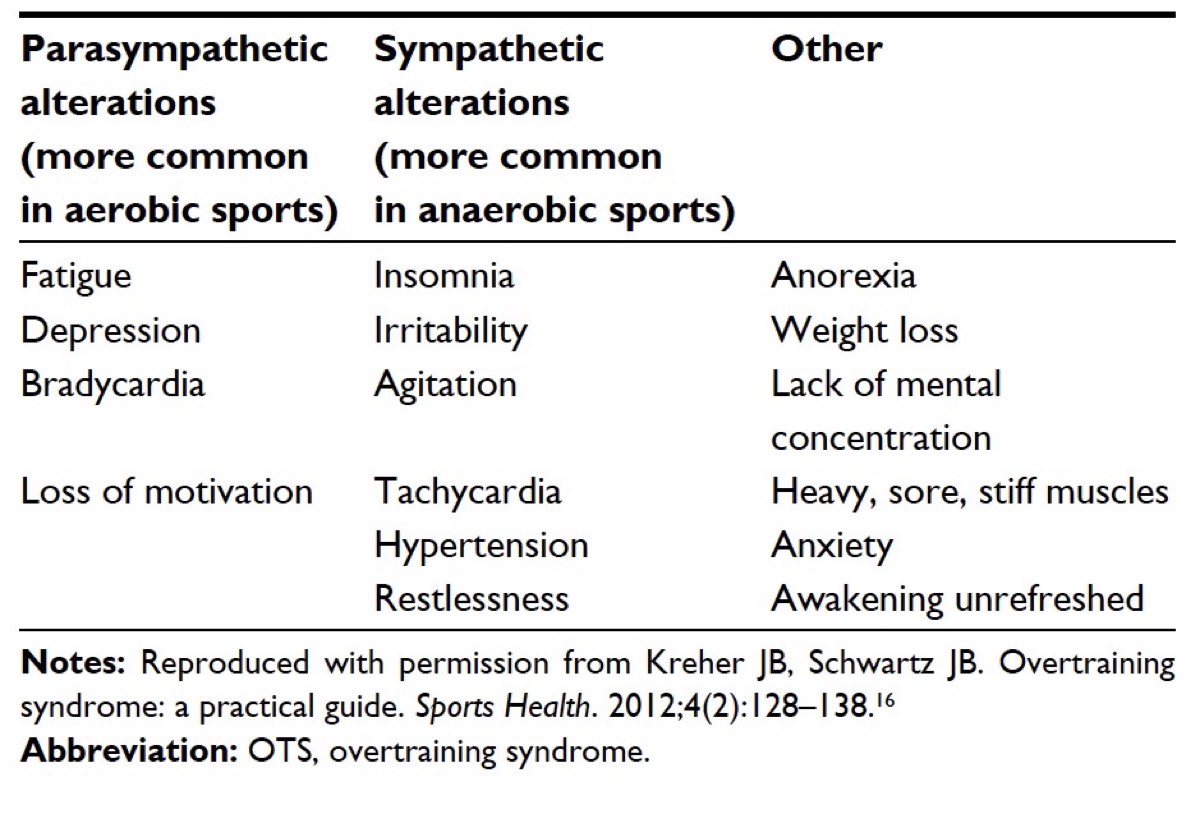

OTS symptoms include performance decrease, fatigue, depression, suppressed heart rate at maximal efforts and increased heart rate at submaximal efforts (you can’t get your heart rate up when you need to and it’s too high the rest of the time), loss of motivation, insomnia, irritability, agitation, restlessness, hypertension, suppressed appetite, weight loss, poor concentration, unexplained muscle soreness, and anxiety (1, 3, 7, 9, 12).

Currently, no easy way to diagnose OTS exists. This is because many other diseases have overlapping symptoms, including iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia, asthma, hypothyroidism (a slow thyroid), immunodeficiency (impaired immune response), hypocortisolemia (low cortisol), chronic fatigue syndrome, and depression. To accurately diagnose OTS, all potential underlying diseases must be ruled out. Thus, an OTS diagnosis a ‘diagnosis of exclusion.’ We’ll talk more later about other emergent possibilities for diagnosing OTS.

The most common OTS symptoms. It should be noted that parasympathetic and sympathetic alterations refer to the two divisions of your autonomic nervous system where parasympathetic is responsible for the ‘rest and digest’ bodily functions, and sympathetic is responsible for the ‘fight or flight’ bodily functions. Additionally, bradycardia means a low heart rate (below 50 beats per minute) and tachycardia means an elevated heart rate (over 100 beats per minute at rest). Image courtesy of Kreher, J. (2016). Diagnosis and prevention of overtraining syndrome: An opinion on education strategies. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine,Volume 7, 115-122. doi:10.2147/oajsm.s91657.

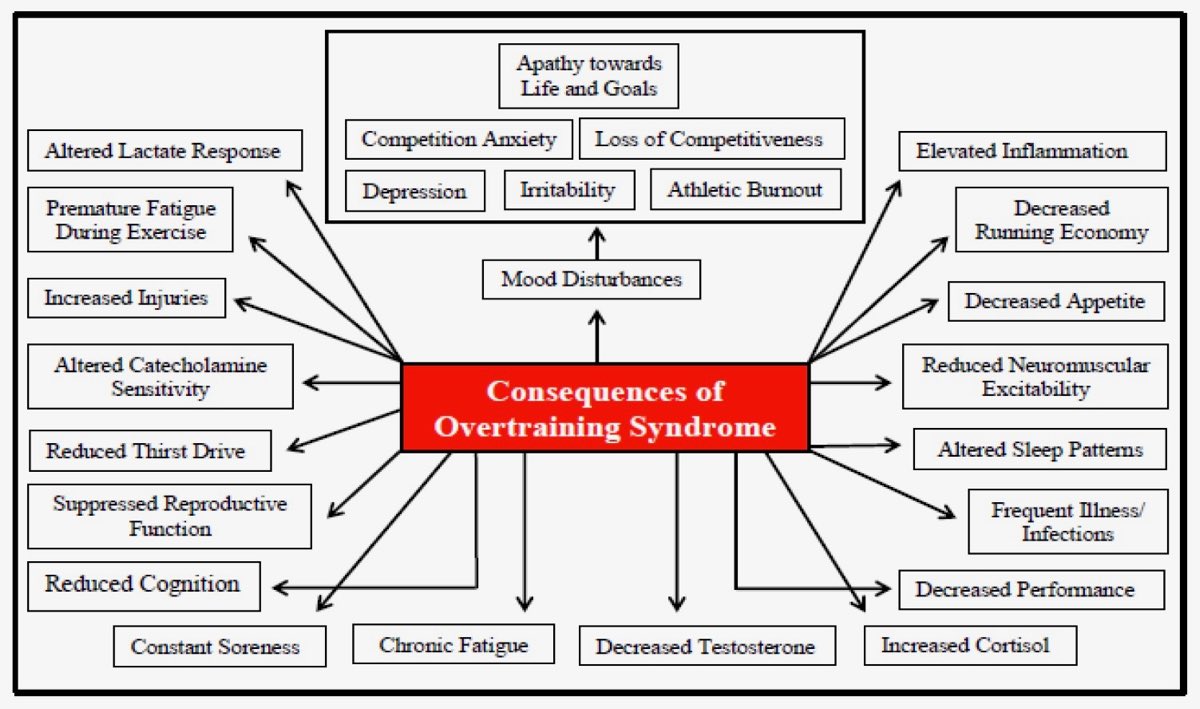

There are many OTS consequences, or symptoms. It should be noted that altered lactate response refers to having a lower blood lactate for a given work rate, which might seem like a positive, being able to do ‘more work’ with less blood lactate building up, however, in OTS a blunted lactate response refers to the inability to work at that same intensity. Additionally, altered catecholamine sensitivity refers specifically to a decrease in sensitivity to epinephrine (or low adrenaline) and dopamine (responsible for neuromuscular function). Finally, it’s because of this decrease in sensitivity that we see a reduction in neuromuscular excitability, or your muscles’ ability to contract to the nerve impulse. Image courtesy of Carter, JG, Potter, AW, and Brooks, KA. Overtraining syndrome: Causes, consequences, and methods for prevention. J Sport Human Perf 2014;2(1):1-14. DOI: 10.12922/jshp.0031.2014.

OTS Contributing Factors

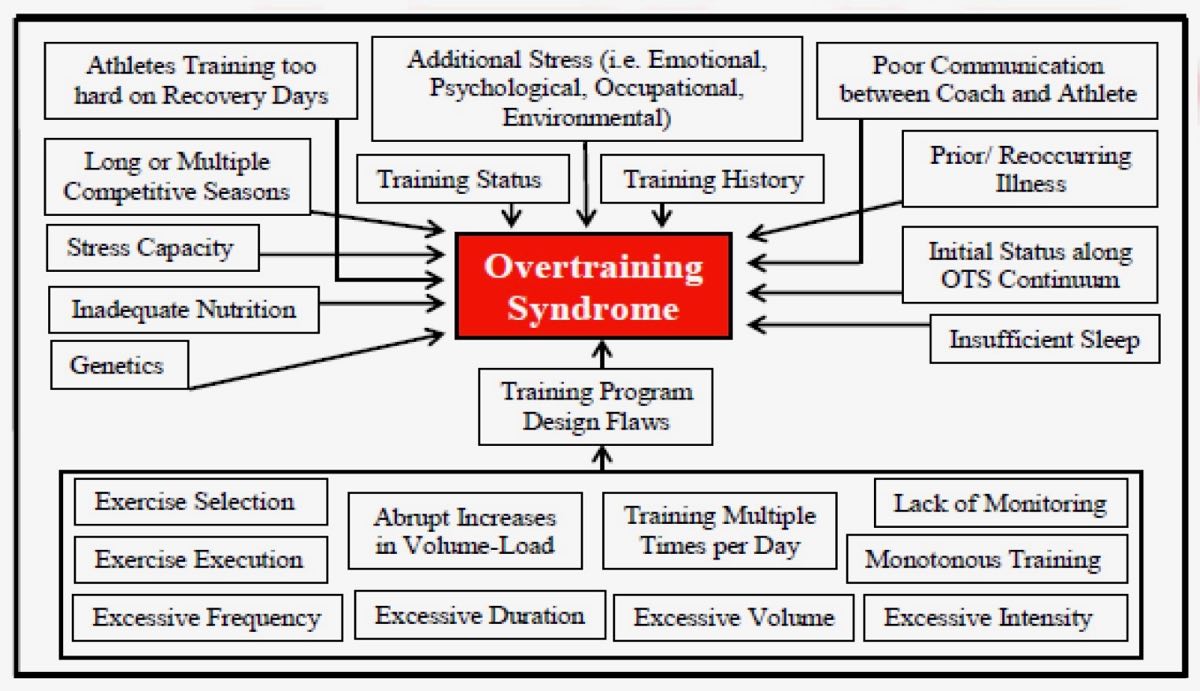

Part of what makes OTS such a difficult condition to see coming is that despite how the name sounds, it’s really hard to over train. More importantly, it is easy to be under recovered. Additionally, stepping off the healthy training continuum into OTS land is generally brought on by more than simply training really hard with not enough rest. Another life stressor is almost always involved.

These outside stresses can be emotional, psychological, occupational, or environmental. That new job kicking your butt, a huge deadline, external pressure to perform, financial problems, a break-up, a new baby, the list goes on: you’re doing the same training you always do and a couple of these stressors stack up against it and this goes on for a while until one day you realize you are more tired than you’ve ever been.

In my case, I went through a fairly traumatic break-up, was not eating enough (likely chronically low glycogen combined with excessive fiber intake), was training too hard on my easy days, had a lack of communication of goals and expectations between myself and my coaches, and felt an immense pressure to perform. It was a perfectly awful storm.

OTS is more than training too much; it generally occurs when multiple factors are at play. Image courtesy of Carter, JG, Potter, AW, and Brooks, KA. Overtraining syndrome: Causes, consequences, and methods for prevention. J Sport Human Perf 2014;2(1):1-14. DOI: 10.12922/jshp.0031.2014.

Possible OTS Pathophysiology and Diagnostic Techniques

A number of hypotheses explain the possible pathophysiology, or the mechanisms, of how OTS occurs and presents itself in our bodies. And it’s also these hypotheses that may help us identify fatigue and possibly OTS in athletes earlier. These hypotheses are the:

- hypothalamic hypothesis;

- glycogen hypothesis;

- oxidative stress hypothesis;

- glutamine hypothesis;

- central fatigue hypothesis;

- autonomic nervous system hypothesis; and

- cytokine hypothesis.

The last one, the cytokine hypothesis, might best summarize all the others and will be our focus. I know that I just overwhelmed you with a huge list of words, but hang in there because I explain most of them below!

The cytokine hypothesis focuses on the maladaptation to excess stress that leads to chronic inflammation (1). Normally when you have repetitive muscular contraction and joint movement during exercise, you cause microscopic tissue damage and your body responds by healing and strengthening the damaged tissues. To do this, the body recruits cytokines, or the proteins regulating immune and inflammatory responses, to the localized inflammation sites (4, 5). However, when you keep reintroducing inflammation via exercise without enough rest for repair, the inflammatory response can go haywire, becoming both amplified and chronic.

The cytokines that we believe to be most prevalent during OTS are interleukin 1 beta (IL-1b), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), which are responsible for regulating the body’s inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses (4). Elevated levels of cytokine act on the hypothalamus, the area of the brain that regulates several metabolic processes, to suppress hunger which in turn limits glycogen stores. Additionally, elevated TNF-α and IL-1b levels have been found in patients with clinical depression and could account for the depression and sleep disturbances experienced during OTS (1).

To tie in the glycogen hypothesis, increased cytokine levels have been shown to decrease concentrations of GLUT-4 transporters, proteins that help to transport glucose in the body and maintain whole-body glucose homeostasis. This down regulation of GLUT-4 transporters might be responsible for that chronic ‘heavy leg’ feeling often associated with OTS because GLUT-4 is primarily found in your muscles (13, 1).

Finally, when it comes to immune-system issues in athletes with OTS, we know that glutamine levels might be involved (4). Glutamine is an amino acid, a building block of protein, with a couple important jobs in this story. Essentially, when the production of cytokines is upregulated in OTS, namely IL-6 and TNF-α, more of our blood-plasma glutamine gets utilized. This happens because glutamine is a precursor to other inflammatory proteins. Glutamine is also crucial in white-blood-cell formation, which combat inflammation. With glutamine being used up in cytokine development, we have an impaired ability to produce white blood cells and this makes us more susceptible to infections, particularly upper-respiratory-tract infections because it’s our first line of defense against bacteria and viruses (4). Additionally, if we have a higher need for glutamine than is available, our body will break down protein stores, namely our muscles, to release more glutamine (18). That’s not good at all!

The last hypothesis that falls under the cytokine family is the possible hypothalamic origins of OTS. When high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines are present, like during OTS, your hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and possibly your hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, are affected. The HPA axis refers to your hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenal glands as if they were one entity. They are critical components of your endocrine system, and when overstimulated by cytokines, they release more corticotropin-releasing hormone and adrenocorticotropic hormone, which both upregulate cortisol (a stress hormone) and in turn suppress testosterone. This has led to some movement in the medical community to monitor or identify OTS with the cortisol-to-testosterone ratio. Unfortunately, these blood values show conflicting results and are thus unreliable in diagnosing OTS (15, 8, 14) or differentiating between NFOR and OTS (1, 3). They are perhaps more reliable in identifying generalized fatigue.

A better marker of OTS might simply be monitoring how cortisol does or doesn’t change following an intense training block where an abnormal, blunted cortisol response, rather than a normal cortisol spike, is a sign of OTS (15). What becomes more complicated however, is that generally OTS is associated with chronically high cortisol levels (7, 14), but HPA axis disorder (often associated with OTS) causes cortisol to more or less bottom out (8). Either way, there should still be a brief cortisol spike in response to training stress, and no change post-exercise would suggest OTS (7, 8, 14).

As previously mentioned, often times these tests cannot differentiate between NFOR and OTS. It should also be noted that because it would be unethical to induce OTS in study participants, researchers have to find athletes who ‘likely have’ OTS or artificially induce a high training dose for a short time period, both of which create many research limitations.

This probably sounds discouraging. Why did we just learn all that if none of it offers concrete solutions? Through all this research, we have gained a much better understanding of the mechanisms responsible for OTS. While it appears that monitoring blood levels for white blood cells, cortisol versus testosterone, and plasma glutamine levels might not allow us to clearly diagnose OTS, they could allow us to catch the earlier stages of fatigue, differentiate between FOR and NFOR, and hopefully catch athletes before they move from NFOR to OTS (7, 8, 14).

Now, let’s talk about the older, tried-and-true metrics that do a fairly good job of monitoring for NFOR and OTS. Those include monitoring for depressed submaximal and maximal blood-lactate values, a suppressed heart rate at maximal efforts, a higher heart rate at submaximal efforts, and mood disturbances in conjunction with performance decreases (15). The negative lactate and heart-rate changes are survival mechanisms, with your body limiting the amount of work (and damage) you can do. When those physiological markers are combined with a subjective marker, such as mood issues or workouts feeling harder than they should, we can we begin to assess for OTS.

One newer, novel, way to diagnose OTS is with a psychomotor test. Psychomotor tests generally assess precision, coordination, dexterity, control, and reaction time. The idea to use these tests as a new way of looking for OTS came from OTS sharing so many similarities with chronic fatigue syndrome and depression, which generally cause a slowing of these faculties (6). In studies looking at reaction time between healthy individuals and those with depression, the depression population reported reaction times that were 26% slower than the healthy group (6). However, research in this field is in the early testing stages.

Essentially, if OTS symptoms last longer than two months (especially after a two- to three-week training break), make an appointment with your primary-care provider to rule out any other underlying conditions and then dive in from there as the scientific community continues to work out this puzzle.

How Do You Avoid OTS?

- Evaluate your individual time and place. Sometimes OTS is confused with burnout, but generally when an athlete experiences burnout, they have a loss of motivation but otherwise remain healthy. An athlete with OTS could still possess a strong desire to train and race but is experiencing health problems. If you are still chomping at the bit and not struggling to tie your shoes or get out of your car at the trailhead, you are likely not ‘simply’ burned out.

- Know that there is no one OTS cause. Be aware of non-running stress and make sure to get adequate sleep. Sleep is a critical part of fatigue management. Inadequate sleep may not only impair your recovery, but it can also affect your mood, reaction times, attention, wakefulness, neuroendocrine function, cardiovascular performance, and general cognition (3, 11).

- Eat enough of the right foods. In a study in Scandinavia, they found that women who had chronic low energy availability (likely from disordered eating) were far more susceptible to chronic fatigue syndrome and OTS (17). Additionally, this research found that the participants who were part of the low-energy-availability group generally ate diets high in fiber and lower in fats and protein. Not only did the high-fiber diet likely act as an appetite suppressant but it also caused drops in estrogen levels. This is because estrogen, like fats, bonds to fiber and is then excreted via the digestive tract instead of being reabsorbed into the body (17). Additionally, chronic carbohydrate depletion, dehydration, and a negative energy balance causes a stress response in the body, stimulating stress hormones and reducing insulin levels, which can cause overreaching symptoms outside of training (3).

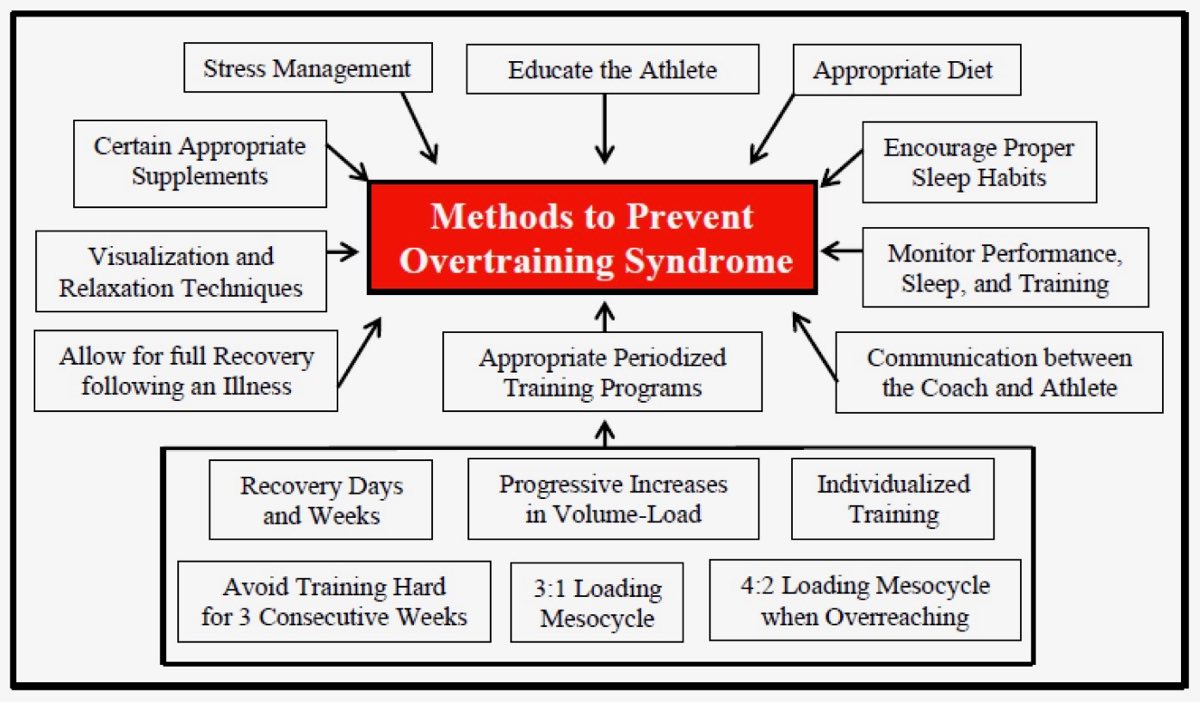

- Avoid making common training mistakes. Specifically avoid monotonous training that does not include any variability in your intensity. Depending on your training history, take one day of complete rest a week, or one complete rest day every other week with a day of recovery-paced, short cross training every other week. Your body needs those quiet moments to have the energy to adapt to the bigger training stimuli. This includes keeping an eye on the big picture and planning out a race season that provides you with an adequate amount of rest from week to week, between blocks of training (every three to four weeks), and including a rest season.

- Monitor your training and recovery. Use the tools you have access to, your paper training log, your Excel spreadsheet, and your subjective measures about how the intensity felt as compared to the prescribed workout and your mood. Often times the first sign of OTS is a performance reduction, however that could come in many forms including changes in perceived exertion, coordination, endurance, lactate threshold, power, strength, and overall fatigue (11). All of the diagnostic-test stuff is great, but the more powerful information often comes from personal reflection.

- Communicate. A communication breakdown in training, racing, or life can cause additional stress. Talk to your coach, partner, training partners, and support network. In the coach-athlete relationship, inadequate communication can lead to a misunderstanding of expectations, goals, and motivation. Be an advocate for your well-being.

There are many things you can do to prevent OTS as an athlete, parent, friend, training partner, or coach. Largely this relies on resting enough and being cognizant of outside stressors. It should be noted that 3:1 loading mesocycle refers to a standard three weeks of building training with one week of lower volume/recovery, also called a mini-cycle. Additionally, a 4:2 loading mesocycle when overreaching means that if you are intentionally ramping up volume over that mini-cycle to a greater degree than normal, take an added week of rest and recovery. Image courtesy of Carter, JG, Potter, AW, and Brooks, KA. Overtraining syndrome: Causes, consequences, and methods for prevention. J Sport Human Perf 2014;2(1):1-14. DOI: 10.12922/jshp.0031.2014.

[Editor’s Note: Back in 2013, physical therapist and iRunFar columnist Joe Uhan wrote a three-part series on overtraining syndrome. Check out his Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.]

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- Have you had a diagnosis of non-functional overreaching or overtraining syndrome from a medical professional? If so, would you share to care a little about the experience, such as what the doctor thought your compounding causes were, your symptoms, the criteria/testing used to make your diagnosis, and how the recovery process went?

- Have you had over-fatigued feelings that took an abnormally long amount of time to recover from, but for which you didn’t receive a professional diagnosis? If so, could you share a little bit about your experience as well?

- What are the non-running life stresses that you have to factor into your personal training-rest-stress equation? How much extra rest have you found these life stresses to require?

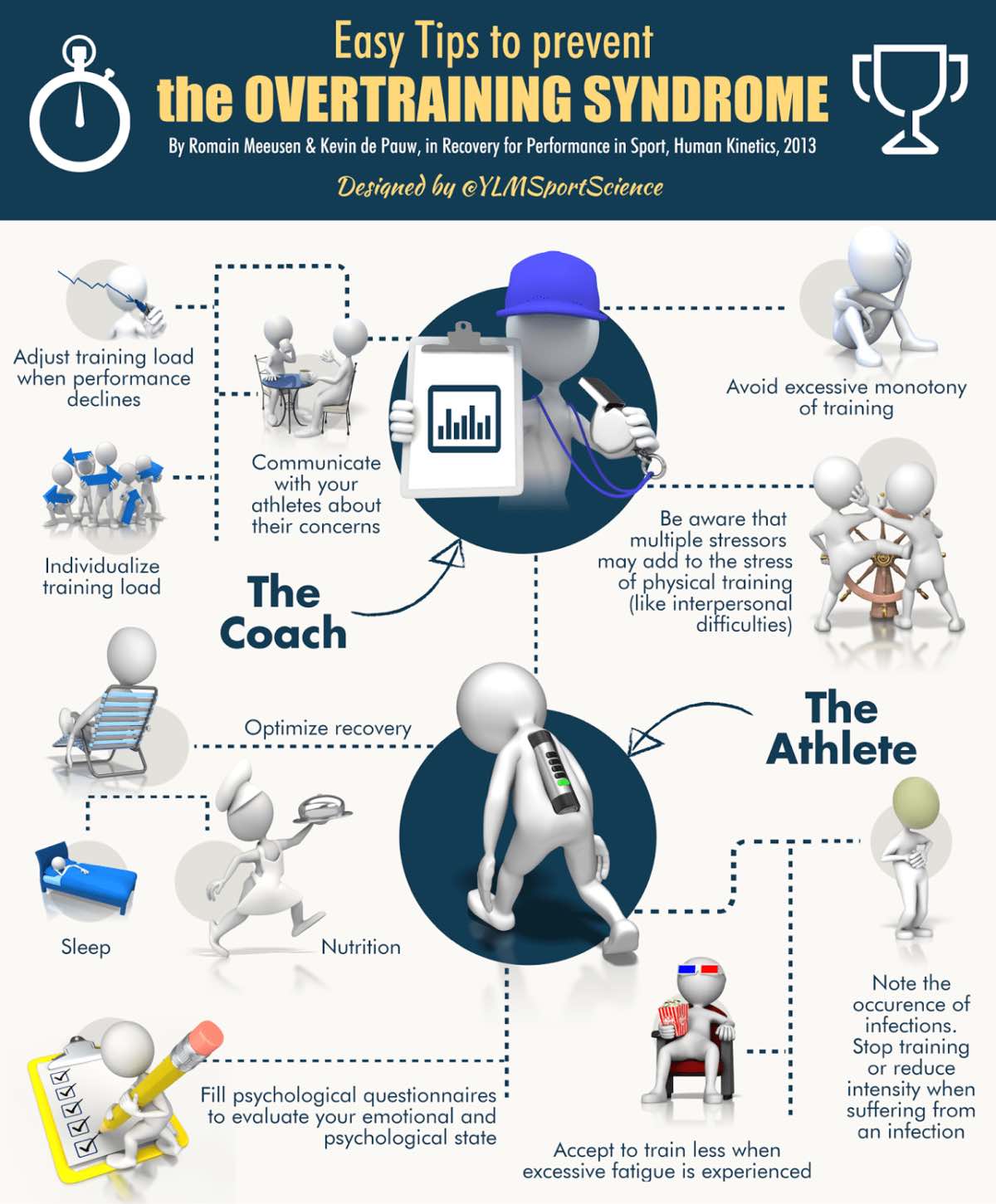

Easy tips to avoid OTS. Image courtesy of Ylmsportscience.com/2014/12/03/training-workhard-easy-tips-to-prevent-the-overtraining-syndrome-by-ylmsportscience/.

References

- Carfagno, D. G., & Hendrix, J. C. (2014). Overtraining Syndrome in the Athlete. Current Sports Medicine Reports,13(1), 45-51. doi:10.1249/jsr.0000000000000027

- Morgan, C. A., Wang, S., Mason, J., Southwick, S. M., Fox, P., Hazlett, G., . . . Greenfield, G. (2000). Hormone profiles in humans experiencing military survival training. Biological Psychiatry,47(10), 891-901. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00307-8

- Meeusen, R., Duclos, M., Foster, C., Fry, A., Gleeson, M., Nieman, D., . . . Urhausen, A. (2013). Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: Joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science (ECSS) and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). European Journal of Sport Science,13(1), 1-24. doi:10.1080/17461391.2012.730061

- Kreher, J. B., & Schwartz, J. B. (2012). Overtraining Syndrome. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach,4(2), 128-138. doi:10.1177/1941738111434406

- Kreher, J. (2016). Diagnosis and prevention of overtraining syndrome: An opinion on education strategies. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine,Volume 7, 115-122. doi:10.2147/oajsm.s91657

- Nederhof, E., Lemmink, K. A., Visscher, C., Meeusen, R., & Mulder, T. (2006). Psychomotor Speed: possibly a new marker for overtraining syndrome. Sports Medicine,36(10), 817-828. doi:10.2165/00007256-200636100-00001

- Urhausen, A., Gabriel, H., & Kindermann, W. (1995). Blood Hormones as Markers of Training Stress and Overtraining. Sports Medicine,20(4), 251-276. doi:10.2165/00007256-199520040-00004

- Anderson, T., Haake, S., Lane, A., & Hackney, A. (2016). Changes in resting testosterone, cortisol, and interleukin-6 as biomarkers of overtraining. Balt J Sport Health Sci,101(2), 2-7.

- Aubry, A., Hausswirth, C., Louis, J., Coutts, A. J., Buchheit, M., & Meur, Y. L. (2015). The Development of Functional Overreaching Is Associated with a Faster Heart Rate Recovery in Endurance Athletes. Plos One,10(10). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139754

- Deneen, W., & Jones, A. (2017). Cortisol and Alpha-amylase changes during an Ultra-Running Event. International Journal of Exercise Science,10(4), 531-540.

- Carter, JG, Potter, AW, and Brooks, KA. Overtraining syndrome: Causes, consequences, and methods for prevention. J Sport Human Perf 2014;2(1):1-14. DOI: 10.12922/jshp.0031.2014

- Coates, A. M., Millar, P. J., & Burr, J. F. (2018). Blunted Cardiac Output from Overtraining Is Related to Increased Arterial Stiffness. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise,50(12), 2459-2464. doi:10.1249/mss.0000000000001725

- Sims, S. (2001). The Overtraining Syndrome and Endurance Athletes. Strength and Conditioning Journal,23(1), 45. doi:10.1519/00126548-200102000-00010

- Cadegiani, F. A., & Kater, C. E. (2018). Hormonal response to a non-exercise stress test in athletes with overtraining syndrome: Results from the Endocrine and metabolic Responses on Overtraining Syndrome (EROS) — EROS-STRESS. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport,21(7), 648-653. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2017.10.033

- Halson, S. L., & Jeukendrup, A. E. (2004). Does Overtraining Exist? Sports Medicine,34(14), 967-981. doi:10.2165/00007256-200434140-00003

- Birrer, D., Leinhard, D., Williams, C., Rothlin, P., & Morgan, G. (2013). Prevalence of non-functional overreaching and the overtraining syndrome in Swiss elite athletes. Schweizerische Zeitschrift Für Sportmedizin Und Sporttraumatologie,61(4), 23-29.

- Melin, A., Tornberg, Å B., Skouby, S., Møller, S. S., Sundgot-Borgen, J., Faber, J., . . . Sjödin, A. (2014). Energy availability and the female athlete triad in elite endurance athletes.Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports,25(5), 610-622. doi:10.1111/sms.12261

- Mittendorfer, B., Gore, D. C., Herndon, D. N., & Wolfe, R. R. (1999). Accelerated Glutamine Synthesis in Critically III Patients Cannot Maintain Normal Intramuscular Free Glutamine Concentration.Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition,23(5), 243-252. doi:10.1177/0148607199023005243