Back in my college running days, I remember debating with a teammate about weekly mileage. Well actually, that was a common debate topic, but this one stands out in my memory. I had just run over 100 miles in the previous seven days. My body was a wreck, but I could finally say that I ran my first 100-mile week. I was psyched until my teammate insisted that it didn’t count because the seven days fell outside of the normal Sunday-to-Saturday calendar week. Eventually, I conceded and started my next week with a long run so that I could get a head start on a “real” 100-mile week.

Looking back at that experience now makes me wonder why the calendar had so much power over my training plan. (And I won’t even begin to get into the arbitrary nature of a 100-mile week right now.) It also makes me realize that I may have grown somewhat wiser in the years since college, but I still rely heavily on a calendar to decide my training structure. I even remember a similar philosophical debate I had with myself when I started logging my runs on Strava that (gasp!) would organize my training weeks from Monday to Sunday instead of Sunday to Saturday like a physical calendar. I would still be doing the same training, but somehow it felt all wrong.

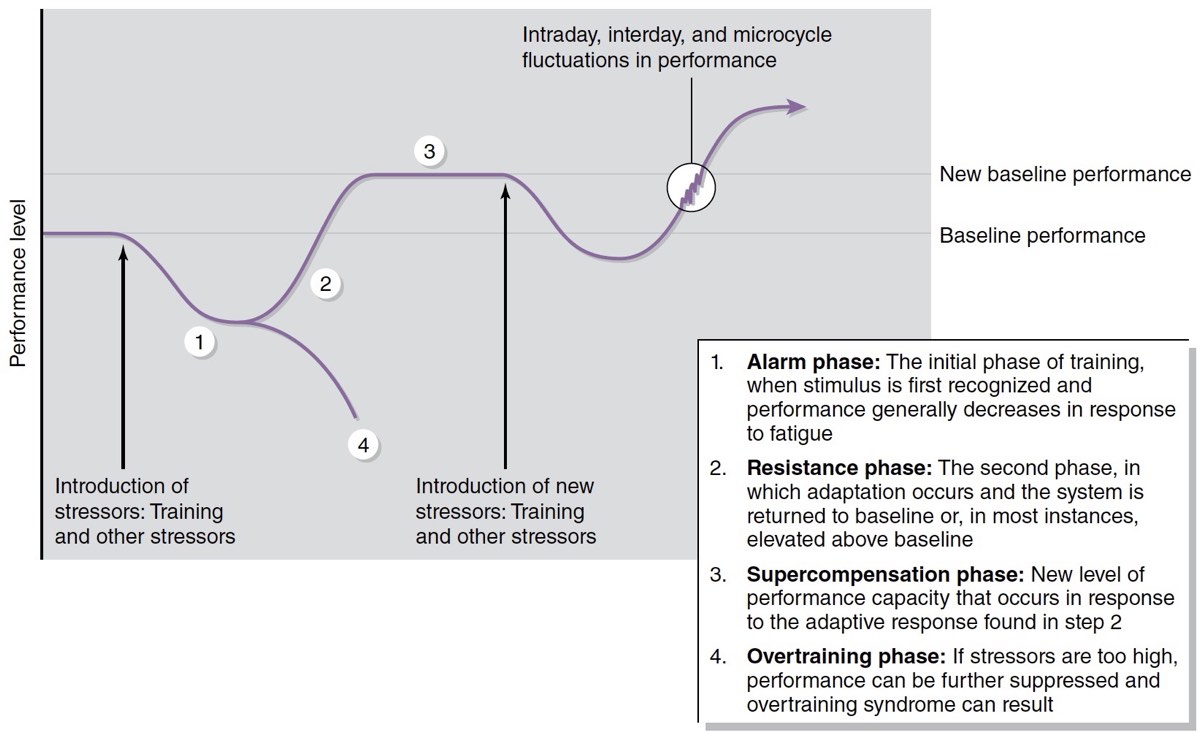

How has this happened? How have I and many like me become so dependent on the seven-day training structure? Part of the answer comes from a basic training principle: periodization. For a good primer on periodization, check out this iRunFar article by coach Ian Torrence. To quickly summarize, periodization breaks training down into macrocycles that last several months to a year, mesocycles that last two to six weeks, and microcycles that last several days to two weeks (1). The figure below illustrates how proper periodization optimizes stress and recovery to improve performance.

How proper periodization can optimize stress and recovery to improve performance. Image: Haff, G., & Triplett, N. T. (Eds.). (2016). Essentials of strength training and conditioning. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics (1).

For many runners, the microcycle in their training plan is a week. A normal, seven-day week allows us to easily compare workouts and volume from previous weeks based on our training calendars. A seven-day microcycle is just really convenient. However, when we decide that a microcycle must begin and end on the same days of the week, every week, we are not always considering the overarching goals of a good periodized plan.

Zaryski and Smith (2) explain that the success of a periodized plan for ultra-endurance athletes depends on the principles of all-around development, overload, specificity, individualization, consistent training, and structural tolerance. In my experience as an athlete and coach, individualization is one of the most important principles of any training plan. The authors go on to explain that, “Individual athletes will react and adapt differently when presented with identical training regimes” (2). This is a simple, but hugely important factor of training-plan development. That varied individual-response factor makes me reconsider why the most commonly used microcycle is based on a seven-day week. If each person responds to training stimuli differently, wouldn’t their recovery times vary as well? And if each person recovers from training differently, then why is the weekend long run so ubiquitous?

Once we start to ask these questions and rethink the goal of each microcycle, we can begin to problematize the seven-day training calendar. What if it takes five days to fully recover from a workout, but you only have two days before your next long run? In this case, maybe a 10-day microcycle would make more sense. The important thing to remember is that we are not machines and we are all different. We so often judge the value of our training on the results of a seven-day microcycle, just like I did as a college athlete. That outlook is too narrow and it does not align with the goal of a quality periodization plan.

This is a tricky subject because I know that much of our lives does revolve around the calendar. Most people have weekends free for long runs, and cannot give full priority to the training schedules. But what I hope you can take away from this article is that flexibility is beneficial and perhaps there are times in your life and training when flexing from the seven-day paradigm will help you achieve better results. In the case of my college training story, my body was feeling the effects of a 100-mile training week, even if it wasn’t reflected on my training log. Each day of training builds on itself and our bodies don’t suddenly start all over again once we hit Monday morning. If you can reflect on that, then you will have a better chance of adapting to your training and reaching your next level of fitness.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- Have you ever converted to “training weeks” that are longer than a calendar week? If so, for what purpose and how did it work out?

- Do you ever feel like your training could be organized better beyond the limitations of the calendar week?

- Does the calendar week actually work well for you?

References

- Haff, G., & Triplett, N. T. (Eds.). (2016). Essentials of strength training and conditioning. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Zaryski, C., & Smith, D. J. (2005). Training principles and issues for ultra-endurance athletes. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 4(3), 165–170.