[Editor’s Note: Welcome to iRunFar’s new ‘Running on Science’ column, which will be authored monthly by Tracy Beth Høeg and Corrine Malcolm. The goal of ‘Running on Science’ is to interpret the established and ongoing research and theory in the field of endurance running in a way that’s not only understandable and useful for your own running, but also interesting. ‘Running on Science’ will operate in the genre of science writing. Enjoy!]

Dawn was breaking over Long Lake outside of Steamboat Springs, Colorado, when Courtney Dauwalter realized she was having trouble seeing the details of the trail ahead of her. She was leading the female race at the 2017 Run Rabbit Run 100 Mile and had only about 12 miles to the finish. She took out her contacts, wondering if they were distorting her vision. But her vision remained cloudy, and shortly thereafter she tripped and flew, hitting her head on a rock. Fluid was running down her face; she could not see the color of it, but it turned out to be blood. This was far from the last time she would fall. As she put it, “I was bitin’ the dust hard every quarter of a mile or so.”

Her vision worsened to the point she could no longer even see shadows. Her visual acuity (or lack thereof) would easily qualify as “legal blindness” to eye professionals. With just a few miles to go, Courtney used her husband as a makeshift blind guide: He verbally instructed her where to turn, lift her feet, and more. Incredibly, she ended up winning the female race, and her experience was brilliantly documented on Ultra Runner Podcast. Little did she know that, on that very same day, Mark Hammond in the men’s race had begun to lose his vision at mile 70.

Interestingly, a year prior, Chuck Radford’s experience with vision loss at the very same race was documented on the same podcast. Chuck mentioned that he was one of three runners at one aid station who had lost their vision that year(!). Their symptoms all sounded consistent with what we have come to call ultramarathon-associated visual impairment (UAVI), or as I like to say, “oooahhvee.”

Back in 2013, I flew to California from Denmark to begin navigating the uncharted territory of vision loss among ultramarathon runners with Dr. Marty Hoffman. He had, much to his surprise, noted in a survey study (Hoffman, 2011), that vision problems developed in 2.1% of 100-mile finishers and in 3.6% of non-finishers. I ran this by all the ophthalmologists in my department in Næstved, Denmark, one morning and they were both baffled and interested. One of the doctors suggested that the vision loss may be due to hypoglycemia, or blood sugar that’s too low. I doubted this, being a seasoned ultrarunner myself. After all, unless you take insulin, a runner’s (or anyone else’s) blood sugar should never go so low as to induce sustained vision loss. But honestly, I could not even wager a guess.

Marty Hoffman, Kim Corrigan, and I were able to, in a matter of just a couple months, recruit 173 people from the United States and abroad with a self-reported history of “significant visual difficulties” during an ultramarathon (Høeg, 2015). We had posted advertisements on websites and listservs and never expected to be able to study so many runners. As I read through the survey results, it became quickly apparent that nearly every single one of these runners had experienced the same constellation of symptoms, and many of them over and over again.

What exactly did they experience? Painless clouding of their vision that would get progressively worse and not go away until they stopped running.

At this point, most humanoids would have the following internal monologue: Running seems to be causing me to go blind. Maybe I should stop. But not ultramarathon runners. They keep running. This is what makes them (us) such an interesting breed to study.

And study we did, because we still did not know what was happening to the eyes.

What We Know so Far

Current Ultramarathon-Associated Vision Loss Survey Results

Here is what we were able to learn from the 173 survey participants with a total of 779 episodes of ultramarathon-associated vision loss:

- Symptoms resolve spontaneously after cessation of running; median time to recovery was 3.5 hours and all recovered within 48 hours*

- Bystanders tend to describe the appearance of the cornea(s) as “milky white”

- Only 10/173 research participants had had an eye examination while they still had vision loss

- 8/10 of those with an exam had corneal edema

- 2/10 had a diagnosis of “contact lens irritation.” This is expected to be painful and resolves with removal of contact lenses. While contact-lens irritation should be considered in runners with vision loss wearing contact lenses, we do not consider contact-lens irritation to be the classic form of ultra-related visual impairment.

*One participant in our study reported visual issues for six to eight months following his race; however, it was not clear if the vision loss was related to the race or was indeed a case of UAVI. This participant was lost to follow-up preventing further investigation of the case.

Our study suggested that UAVI is most often a self-limited, painless clouding of the vision due to corneal edema.

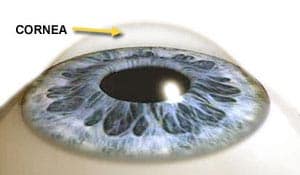

What Is the Cornea and What Is Corneal Edema?

The cornea is the protective, clear, dome-shaped layer of tissue that covers the front of the eye, in front of the pupil and the lens. In corneal edema, the cornea becomes excessively filled with fluid and loses its transparency.

UAVI-like corneal edema is also known to occur in long-distance cycling events. Below is a picture of a participant in the Leadville Trail 100-Mile Mountain Bike Race. Corneal edema is apparent in his left eye.

Left medial corneal opacity at the finish line of a 100-mile mountain bike race. Photo: Khoadee & Torres, 2016

Magnification of left medial corneal opacity at the finish line of a 100-mile mountain bike race. Photo: Khoadee & Torres, 2016

This cyclist began to experience painless loss of vision in his left eye after 93 miles of riding, which fully resolved within three days (longer than the resolution of symptoms for any participant in our running study). (Khoadee & Torres, 2016)

While I was writing this article, my friend and fellow ultramarathon physician researcher, Dr. Michael Campian, told me he had seen a photo of Mark Hammond’s eye from this year’s Run Rabbit Run 100 Mile. Mark was very kind to give me permission to use his photo and name for this article.

The below photo of Mark Hammond clearly demonstrates corneal edema in the left eye. He took this photo at the race. He developed vision loss in his left eye beginning around mile 70. “It was about four hours after I took off my sunglasses [that the cloudiness developed]. My eye didn’t hurt and the cloudiness went away a few hours after the race. The exact same thing happened at last year’s [race]. It has happened on two other occasions, and they were also times when I was running for several hours without eye protection.”

Why Is Corneal Edema Happening at Endurance Events?

One theory is that stress to the cornea (hypoxia/altitude, cold, dehydration, debris, wind, etc.) can lead to a buildup of corneal lactate, which can act as an osmolyte in the cornea (the reverse of what happens to a cucumber when you turn it into a pickle), drawing more fluid in. The corneal acidosis from lactate buildup may further contribute to the swelling by inhibiting the cornea’s tiny pumps that push fluid out and keep our vision clear. In addition, there may be inadequate frequency of blinking. This idea came up because the blink reflex is known to be altered after refractive surgery and refractive surgery is a major risk factor for developing UAVI.

Known Risk Factors for UAVI

- Refractive surgery: Ultrarunners with a history of UAVI are approximately twice as likely to have had refractive surgery (such as LASIK) on their corneas than a reference group of “standard” 100-mile race registrants (p=0.001). Participants with refractive surgery were also more likely to have repeat episodes of UAVI (p=0.01). I just need to pause for a minute to acknowledge what a big finding this was. Ophthalmologists who perform refractive surgery are fond of saying this is a nearly risk-free procedure. However, if you like running ultras, this is a risk to be aware of. The reasons this procedure increases the risk of UAVI is not yet known, but may be because it disrupts the normal function and tissue of the cornea such that fluid can accumulate more easily. Alternately (as stated above), LASIK surgery has been found to interfere (by disrupting the nerves) with the normal blink reflex, thereby potentially predisposing to both corneal edema and frozen cornea (discussed later in this article).

- Long races: The mean (±SD) distance at which visual impairment began was 45 miles. The 100-mile distance was the most common race distance in which survey participants reported vision impairment, accounting for 46.8% of episodes.

Other Variables We Analyzed

- Running with contact lenses was not found to increase or decrease the likelihood of visual impairment

- Visual impairment can occur across a wide range of ambient temperatures, not necessarily in the heat or cold

- Significant wind was reported in only 23% of cases, so was far from the only cause. Also, if wind or debris were the only cause, contact lenses would be expected to prevent UAVI, but they don’t seem to.

- Altitude (>2000 meters) was reported in only 32% of cases and the most frequent altitude UAVI occurs at is at or around sea level.

Preventive Strategies

- Participants with repeat episodes of UAVI have frequently mentioned having success with protective eyewear.

- I was in contact with runner Mitch Chazan in writing this article, who had numerous episodes of UAVI before trying the Wiley X Sg-1 Matte Adjustable Strap Sunglasses. Since he started using these several years ago, he has not had another episode. A nice feature of these glasses is you can switch the lenses out for no tint at night.

- Runners have also reported success preventing UAVI with regular use of lubricating eye drops. I understand “natural tears” are more effective than “artificial tears.”

Treatment

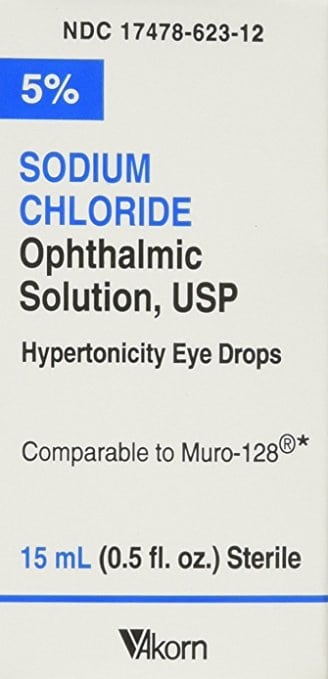

- When we published our article (Høeg, 2015), it fascinated us that none of our participants had found an effective treatment for reversing the vision loss other than stopping running and giving the eyes a chance to rest. In writing this article, I reviewed the medical literature on treatment of corneal edema and ran across the interesting idea of 5% hypertonic saline eye drops. I discussed this with Dr. Miranda Bishara, an ophthalmologist affiliated with the University of Kansas with specialty training in cornea and refractive surgery, who stated: “ophthalmic hypertonic saline drops are used frequently to help decrease corneal edema… I don’t recommend patients use them more than four times [per] day.” She recommends racers use the drops rather than the ointment as they work more quickly and do not cause additional blurring of the vision. I have started recommending runners with frequent UAVI carry a small bottle of these drops during their races (or stash a couple bottles in drop bags) to use if vision loss develops, but have yet to receive any feedback on this idea. (Please let me know if you try the drops and how effective they are!) Also, race medical personnel may consider including a bottle in their medical kit, which would not only be a potentially effective treatment but also clinch the diagnosis of corneal edema if effective.

Other Potentially Exercise-Related Eye Conditions

- Corneal abrasion is frequently suspected, though this appears to be the incorrect diagnosis, in cases of classic UAVI. That is not to say that corneal abrasions don’t happen while running. The most important distinction is that corneal abrasions are painful, while corneal edema is not. Additionally, a corneal abrasion will not look white to anyone looking at the runner’s eye. Corneal abrasions will also have a specific defect on the surface (epithelium) of the cornea that can be readily seen under a black light with yellow (fluorescein) eye drops.

- Frozen cornea or the “Hellgate Eye” reported at the Hellgate 100k in Virginia appears to be an entirely different entity in which the cornea literally freezes in the cold. This is also known to occur in sled-dog races in Alaska. Soldiers, pilots, skiers, cyclists, ice skaters, and snowmobilers have all been reported to develop frozen cornea. This can be treated by warming the corneas, i.e. removing the cold exposure and closing the eyes. (Warming blankets and similar may also be used.) Shielding the eyes with form-fitting glasses/sunglasses or goggle-type glasses would also probably work to help prevent this by trapping body heat and keeping the corneas warmer.

- Corneal thickness increases at high altitude and may or may not be accompanied by vision loss/distortion. This is not believed to be an exercise-induced phenomenon, but increased corneal thickness at altitude may be a risk factor for UAVI.

- Pain or darkness in relation to vision loss is potentially dangerous and less likely to be corneal edema or classic UAVI. Other causes need to be suspected and ruled out with a prompt examination by an eye professional.

- Persistent tunnel vision and double vision have also been reported to me in relation to running (though outside of our study set) and runners who experience either of these should be examined by an eye professional.

What to Do If Vision Loss Happens to You in an Ultra

First, I want to offer a word of reassurance. Corneal edema, frozen cornea, and superficial cornea abrasions all occur in the corneal epithelium (the top/outermost layer). This is the one layer of the cornea that can easily and quickly regenerate. Because of this regeneration, these conditions (including UAVI) do not cause permanent visual damage.

- If this is your first episode, be sure that what you are dealing with is indeed corneal edema. Ask yourself these two questions: Is your vision whitish cloudy (and not dark) and are your eyes pain free? If your answer is “yes” to both of these questions, you are most likely dealing with UAVI from corneal edema. If your corneas appear cloudy/white (as in the photos above), the diagnosis of corneal edema is even more likely. If the answer is “no” to either of the above, you are advised to stop at an aid station for an examination by a medical professional. If you have persistent dark or painful visual impairment and the cause can not be identified at the race, you should leave the race to seek medical attention.

- If you suspect you have ultramarathon-associated corneal edema, or have had it in the past, 5% hypertonic saline drops may be applied to the affected eye(s). My personal strategy would be to apply them as soon as the visual impairment starts.

- If you believe you have had UAVI from corneal edema in the past, you may choose to buy protective eyewear and natural tears to use preventively. You may also consider purchasing 5% hypertonic saline drops to take along with you in case vision loss begins to develop.

Do You Have Information to Add to the Above?

- Our research group continues to be interested in eye-examination records and/or eye photos from runners with ultramarathon-associated visual impairment (UAVI), who were examined while they still have vision loss.

- Have you had any long-term vision or eye issues following an episode of UAVI? If so, we are interested in hearing from you.

- If you or anyone you know ends up using 5% hypertonic saline drops to treat their UAVI, we would love to know how effective it was. I am in the process of submitting for approval a survey-based study of runners who have used 5% hypertonic saline drops to treat their UAVI. Please contact me at [email protected] if you are interested in participating.

References

Hoffman, M.D. and Fogard, K. Factors related to successful completion of a 161-km ultramarathon. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2011; 6: 25–37

Høeg, T.B., Corrigan, G.K., and Hoffman, M.D. An investigation of ultramarathon-associated visual impairment. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015; 26: 200–204

Khoadee M & Torres, DR. Corneal Opacity in a Participant of a 161-km Mountain Bike Race at High Altitude. Wilderness Environ Med. 2016; 27: 274 – 276.