Scenario 1:

Your next race is the Uwharrie 100 Mile, and you’re hoping to knock out a 25-mile training run today at Government Canyon State Natural Area in San Antonio, Texas. You’re about 12 miles into the run on the back side of the park when you need to stop to go to the bathroom. You step off the trail and move quickly toward an Ashe’s juniper for some cover. All of a sudden, you feel a sharp pain on the side of your foot and see a large, dark-colored snake disappear into the undergrowth. You’re by yourself, and this part of the park doesn’t see many hikers or runners. Your cell phone is dead.

Question: What should you do?

A. Try and find the snake to see what kind it was.

B. Make a constricting band out of your shoelace and tie it above the bite.

C. Start walking back to the ranger station.

D. Lie down and wait for help.

E. Hope it was a dry bite and continue your run.

Try to answer before continuing.

Answers:

A. Try and find the snake to see what kind it was.

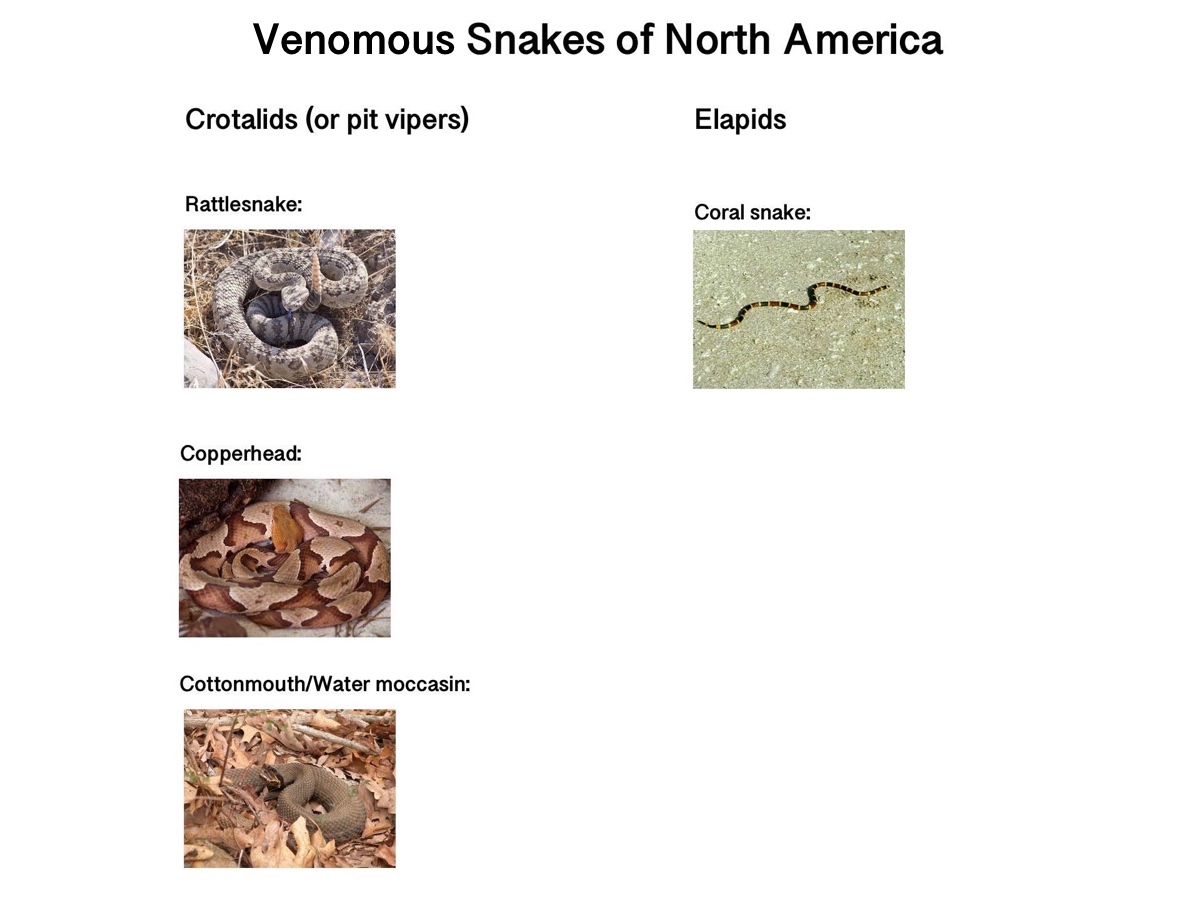

Nope. Here in North America, the only snake identification you need to do is: Did it look like anything like this?

Other than that, you don’t need to know what kind of snake bit you in order to get the correct treatment at the hospital. You will receive a certain amount of antivenin based on the signs and symptoms that you present with, so don’t waste time trying to find the offending snake. (We’ll talk about red, yellow, and black-banded snakes like the one in the above photo at the end of the article.)

B. Make a constricting band out of your shoelace and tie it above the bite.

Nope, not for North American snakes. We have two families of venomous snakes here in North America, the crotalids and the elapids. Our crotalids are pit vipers, and they include rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths/water moccasins. Our one elapid is the coral snake.

Regardless of whether it’s a coral-snake bite or a pit-viper bite, don’t use a constricting band. This is particularly important with pit vipers. They have a tissue-destroying venom that can do more damage when it’s confined to one area with a constricting band or a tourniquet. We’ll talk more about coral snakes at the end of this article.

C. Start walking back to the ranger station.

Yes! Ideally, you wouldn’t move your leg. You’d sit or lie down to decrease the distribution of the venom. But in this situation, a common one for trail runners, you’re unlikely to get any help by staying where you are. You should walk slowly and calmly to the closest place with people. Blowing a rescue whistle is a nice way to attract attention to yourself too.

D. Lie down and wait for help.

Nope. In general, you want to immobilize the bite site to minimize the distribution of the venom, but the primary goal is always to get to a hospital and antivenin treatment if necessary. If you can do both things, great. If you have to choose, choose getting to the antivenin. If you’d been running with a friend, you could send them for help while you waited.

E. Hope it was a dry bite and continue your run.

Nope. While at least a quarter of snakebites are dry and no venom is injected, and even though you won’t be able to make up these training miles, go ahead and call it a day and get yourself to the hospital. You want to be where the antivenin is if you need it.

The scenario continues:

Three miles down the trail, you meet a hiker with a cell phone. What would be the best number to call?

A. Park headquarters

B. 911

C. It depends.

Answer: C. It depends.

In some parks, you’ll receive aid more quickly if your call goes directly to the rangers who have the means and know-how to get to you. But some parks want you to call 911. They have good systems set up to forward your 911 call to the emergency peoples at the park. And some ranger stations aren’t regularly staffed due to underfunding. Look up what you should do in an emergency at the particular park you are in before you head off to play.

The scenario continues:

In this park, the instructions are to call park headquarters, so you do. The ranger at park headquarters tells you to walk slowly to a trail junction where a utility vehicle can meet you. You’re unfamiliar with the trail junction, but thankfully, the hiker has a map. (Carry a map with you when you run on large trail systems!) While you wait for help to arrive, you take off your shoes and running socks to look at the bite. Your notice foot has begun to swell and it’s really starting to hurt.

You wonder if you’re going to die. It’s unlikely. Some 7,000 to 8,000 people get bitten by venomous snakes each year in North America and about five of those people die. So you’re probably not going to die from this bite. Take a deep breath! But you may experience some really unpleasant signs and symptoms.

Pit-Viper Bite Signs and Symptoms

- Swelling and pain

- Bruising and blister formation and later tissue death (There are all sorts of unsettling images online of these particular signs.)

- Weakness, sweating, and chills

- Nausea and maybe vomiting

- Numbness and swollen lymph nodes

Since you don’t know how severe the envenomation is, you must go to the hospital immediately. You will be treated with antivenin there if necessary. Calf sleeves, knee socks, and any jewelry around the bite need to be removed. They can all act like tourniquets as the affected area continues to swell. While you wait, you could wash the wound with water from your water bottle. That’s right, snakebites can get infected like any other puncture wounds. (Insult to injury!)

The scenario ends:

The swelling has progressed halfway up your calf by the time the rangers arrive. They splint your lower leg and lift you into the back of the gator. As you drive to the trailhead where an ambulance is waiting, the ranger tells you how North American snakes are not aggressive and the snake that bit you was just trying to protect itself. You reach the ambulance long before you feel any compassion for the snake. You are given antivenin in the hospital and discharged after two days. You PR at the Uwharrie 100 Mile in October.

Scenario 2:

You are waiting for your runner at the Zion 100 Mile near Virgin, Utah. While you wait, you help organize the drop bags numerically. As you reach under the tarp to pick up a bag that’s been covered, something sharp strikes your hand. You pull back the trap and see this guy.

Photo: Brent Myers

It’s a snake! You holler, “I was just bitten by a snake!!!” Aid-station volunteers and runners’ crews circle around you. A woman pushes through with a snakebite kit. Should you use it to suck the venom out?

Nope. Snakebite kits like the Saywer Extractor will not suck any venom out of a snakebite. Spend your $17 on something else at REI.

“At least three studies, done independently of each other and using different methodologies, arrived at the same conclusion–that the Extractor does not work for venomous snakebites and could make things worse.” This is from Paul S. Auerbach’s wilderness medicine bible, Wilderness Medicine. NOLS Wilderness Medicine also recommends against the use of extractors for snakebites. (They are still mandatory gear at Marathon des Sables though. Please share this article with them.)

A volunteer runs up with a plastic bag full of ice, “Here! Put this ice on it!” Should you put ice on a snakebite?

Nope. Ice isn’t helpful. The venom can cause all sorts of vascular damage, and you don’t want to do anything that would reduce blood flow to the affected tissue further. Cold can make the injury worse. So save the ice for the runners.

More suggestions are bandied about. “I’ve got a stun gun!” “I’ve got meat tenderizer!” “I can pee on it!”

What should you do?

Sit down and try to keep calm. If anybody is searching for the snake, tell them to stop. We don’t need another snakebite in this scenario. Have someone call the emergency number the race director told the aid-station volunteers to call if there was an incident. Or call 911 if there is any delay in getting this number. Keep the folks with tasers, meat tenderizer, and full bladders away from you. If you were envenomated, you need antivenin.

The scenario ends:

An ambulance pulls up to the aid station. They put your arm in a sling and transport you to the hospital where you are given antivenin and discharged the following day. Your runner suffered without your help crewing and pacing, but they crossed the finish line with an hour to spare.

Additional Instructions for Elapid Snakebites

But what about coral snakes?

Many of us are familiar with their red-yellow-black band pattern. And some of us have learned that rhyme to help us differentiate the coral snake from its non-venomous cousins by the order in which the snake’s color banding occurs: “Red on yellow, kill a fellow. Red on black, venom lack.”

Unfortunately, the snakes south of the U.S.-Mexico border never learned this poem. There are very venomous coral snakes out there with red-black band patterns. Moreover, it’s easy to misremember that rhyme. So here’s a new rhyme for you when you’re dealing with striped snakes: It’s a snake. Don’t touch it.

The poem works for any snakes, really.

Coral-snake bites are pretty uncommon, and most people get bitten because they picked the snakes up. Here’s a common scenario from Florida last year. “The [four] folks who were bitten picked up the snakes for either photos or to look at them more closely, according to Battalion Chief Dan Miller. Miller told the Daily Commercial that one snakebite victim took a photo of the snake, posted it to Facebook, and then got bit while still holding it. The snakebite victims apparently mistook the venomous snakes for the non-venomous kingsnake, which can have similar coloration to the coral snake.”

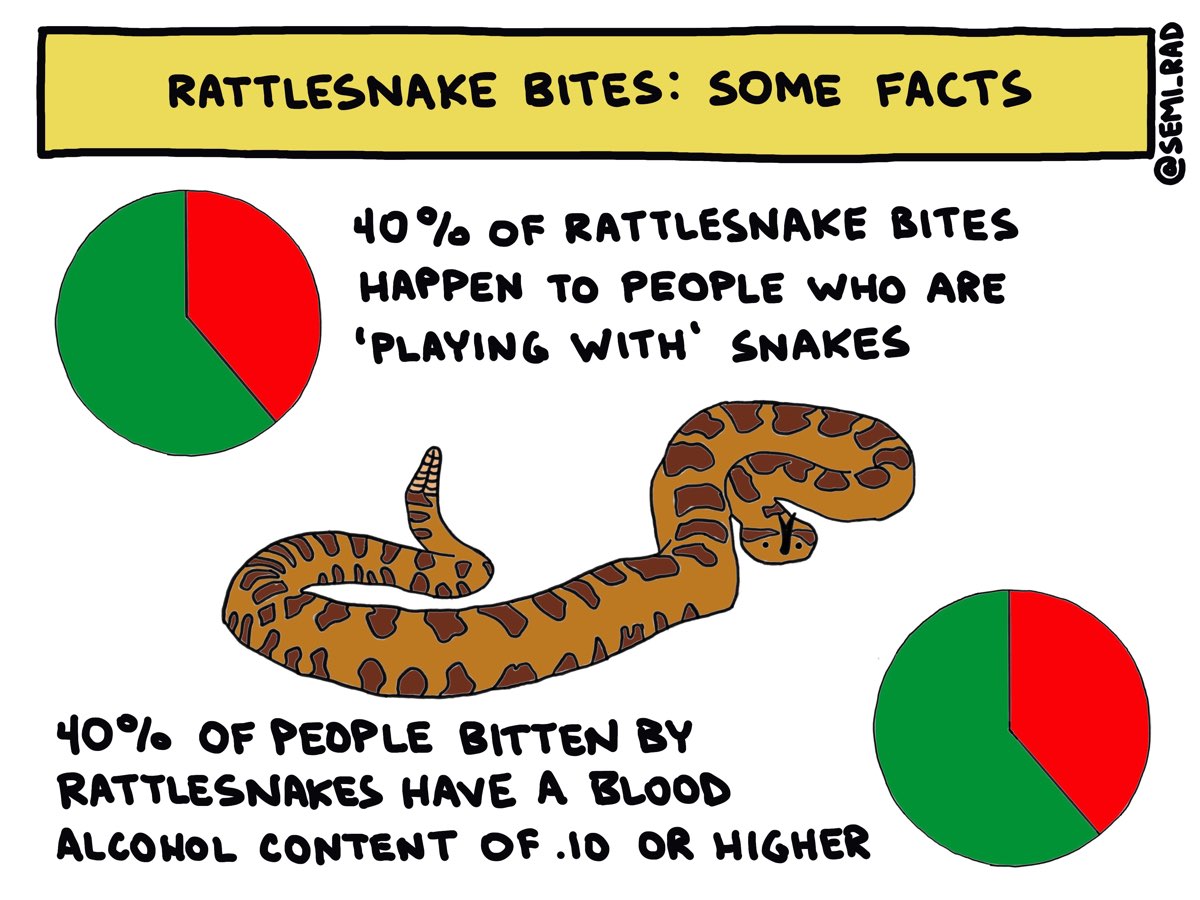

The last death from a coral-snake bite was in 2006, also in Florida. A drunk man got bitten after he picked up a coral snake to kill it. He died before he could get treatment. Before that, no one had died since 1967. If you do manage to get yourself bitten (I’m looking at you, you white male in your twenties who’s drunk and wants to play with snakes; you’re the snakebite-victim demographic), the symptoms are different than pit-viper bites.

Coral-Snake Bite Signs and Symptoms

- Local swelling

- Nausea and vomiting

- Dizziness

- Weakness

- Respiratory difficulty (up to 12 hours after bite)

But the treatment will be the same. Stay calm. Keep the affected body part still. Call for help. A pressure bandage can also be used over a coral-snake bite because the venom is a neurotoxin. It doesn’t destroy the tissue like pit-viper venom does, so trying to limit its distribution to the affected body part is useful. This is not a tourniquet. The pressure bandage should be applied with about the same tension you’d use on a sprained ankle.

But again, you’re wildly unlikely to get bitten by this snake, so I’d focus on remembering the poem: It’s a snake. Don’t touch it.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- Have you ever been bitten by a venomous snake on a run or hike?

- If so, what happened next? How did you get off the trail and to medical care? How were your symptoms, both immediate and longer term? What was the treatment like?

[Author’s Note: Learn more about caring for snakebites in the field and other wilderness first-aid skills with a two-day NOLS course. Thank you to Tod Schimelpfenig, NOLS Wilderness Medicine’s Curriculum Director and author of NOLS Wilderness Medicine, for his guidance and oversight of this series.]

Image: Semi-Rad/Brendan Leonard

[Editor’s Note: Today we conclude the series ‘First Aid on the Run,’ a collaboration between long-time iRunFar columnist Liza Howard, who is a NOLS Wilderness Medicine instructor, and graphic artist Brendan Leonard, of Semi-Rad fame and a trail and ultrarunner himself. Over the last 11 months, ‘First Aid on the Run’ has offered practical, witty how-tos for the first-aid issues and emergencies you may experience while trail running and ultrarunning. Thank you, Liza and Brendan!]