Close to a decade ago, Trail Runner Magazine featured race director and ultrarunner James Varner with the header, “It’s Never Sane with James.” Varner, now 42, has tempered some of his ‘dirtbag’ lifestyle choices over the years, he confirms in our interview: “I’ve chilled out a good bit. I still drink stream water and get myself into trouble in the mountains. But I’ve been eating a much more vegan diet, and I’m not wearing short shorts anywhere near as much,” he says. However, Varner’s ambition, adventurous spirit, creativity, humor, and near-endless drive withstand time.

For the uninitiated, Varner is the founder of Rainshadow Running, a longtime trail and ultrarunning event company in the United States. Varner’s race routes are characterized by challenging features and exquisite landscapes across the Pacific Northwest. He also founded the first-ever Trail Running Film Festival in the U.S. And, he’s an impressive athlete with a 20-year list of ultra-distance accomplishments.

When Varner decided to drop out of college at age 21, he had no idea that ultrarunning existed. Not knowing what to study, he decided to put his energy elsewhere. He became a pizza-delivery dude who enjoyed drinking a lot of cheap beer. That said, Varner also wasn’t the lazy type. He was the oldest of four siblings from a household that revolved around sports. His dad was always on a softball or soccer team and simultaneously coached one of the kids’ sport teams, too. Varner played basketball, baseball, and soccer. In high school, he also joined cross country. But, they lived in Southern Maryland. Trail systems, mountains, and the quintessential ‘outdoor lifestyle’ Varner has today didn’t exist in his world.

“As a kid, my soccer coach would have us run a one-mile singletrack trail after practice—and I totally loved it. That’s my earliest memory of trail running, and that was the longest trail I knew growing up. We didn’t have formal trails. Otherwise, I’d play in the woods and run on deer and cow trails. We were surrounded by water, and we had a canoe. So, I’d go to the beach or play on the rivers. We would also go car camping as a family in the Shenandoah Mountains. The Appalachian Trail runs through there, so we’d do short family hikes,” says Varner.

James (far right) with his family last year. All photos courtesy of James Varner unless otherwise noted.

After closing his college books, Varner got a wild hair to thru-hike the entire Appalachian Trail (AT). He’d never backpacked. Though plenty of people were already doing this, he didn’t know anyone personally who’d had. Social media didn’t yet exist. “I don’t even know where I got the idea. It was 1999. The internet wasn’t what we have today. Other than reading books, there wasn’t a ton of information to figure out the backpack or sleeping bag you should get. I figured it out all on the fly as a beginner in preparation for this big hike,” says Varner.

So, he registered for the Annual Gathering of the Appalachian Long Distance Hikers Association. “It was a weekend campout reunion for long-distance backpackers and wasn’t too far from where I was living at the time. I went and was blown away,” he says.

One of the seminar speakers he watched was none other than David Horton, who talked about his experience running the entire AT, when he became the original fastest-known-time (FKT)-holder.

“I didn’t know anyone ran on trails for more than just a cross-country distance or that people ran more than a marathon distance. I loved David’s stories and talked to him after. He was like, ‘Oh yeah, there are 100-mile, 50-mile, and 30-mile races.’ David is a godfather of the sport and was one of the big influencers of ultrarunning before the internet was a thing. I became one of many people who can thank him for getting me into the sport of trail and ultrarunning. If I’d never met David and never gone to this campout conference, I wouldn’t be where I am today,” says Varner. The conference was full of characters willing to share their experiences, a welcome vibe, and helpful classes on everything from ‘gourmet backcountry cooking’ to ‘building your own backpack.’ Varner left inspired and more prepared to pursue the AT.

“In hindsight, thru-hiking the AT was a 180-degree turn for my life. When I found the AT, I found ultrarunning. Then, I discovered microbrews and bluegrass music and met people who are still my best friends. I had amazing experiences I wouldn’t have had otherwise. I love the direction my life has gone since spending six months in the mountains,” he says.

James and David Horton in 2019, almost 21 years after Horton told James about ultramarathons. Photo: David Horton

Post-AT, he moved to Baltimore with a handful of high-school buddies. A year later, he registered for his first ultrarunning race: the 2001 Hat Run 50k in Susquehanna State Park, Maryland. However, safe and accessible trails were few and far between in the city, and he didn’t own a car, so he didn’t train very much. “I ran the 50k in soccer shorts and the poly-pro shirt I wore on the AT with a Gatorade bottle. This was before gels and trail running vests were a thing. Succeed! salt capsules were just coming out. I was one of the last finishers. I suffered a lot. I totally loved it,” says Varner.

He signed up right away for his second race that took place five months later: the 2001 Catoctin 50k Trail Run. This go around, he lived and worked as a caterer at a summer camp adjacent to the race course’s trails. He trained all summer and was in good shape. The race started with a 100-yard dash across a parking lot to a technical-trail descent. “I was above average at steep and technical downhill trails and I didn’t want to get stuck behind people, so I went out fast. One other guy thought the same thing—but he missed the turn onto the singletrack. I built this huge lead. But, I didn’t want to lead my second 50k ever. On the flat, I slowed way down and walked, but no one caught up. I sat down and stretched. I let one guy go by me and got up to go,” recalls Varner.

Then things started to fall apart. He didn’t know about electrolyte or hydration management. The conditions were hot and humid. He cramped up and slowed down, right as a storm rolled through, so he went hypothermic, he recalls. The next aid station gave him a trash bag to wear. “I finished nowhere near the top. I met a bunch of runners. I was already hooked from my first one but becoming a part of the community in the second one really got me,” he excitedly says.

A few months later, Varner moved out west to a small town on the Oregon coast. He wanted to learn how to farm and became an apprentice. He had a ton of fun pursuing trail running and races. He finished the 2002 Hagg Mud 50k and McDonald Forest 50k. He would’ve done a race a month, he says, but was limited by finances and not owning a car.

“Most of my running in the Pacific Northwest at that time was where the big trees and giant ferns grow, and it rains all the time. And right on the other side of the mountains is the rainshadow: On the east side it’s dry. It’s a positive, cheerful term,” says Varner. And that’s where the name Rainshadow Running came from.

The Capitol Peak Mega Fast Ass 34 miler, in January of 2003, was a life-changer. Varner was 25 years old and finished fourth overall. And through that race, he started giving back to the trail running community, which simultaneously spurred his role as an organizer. “The race director, John Pearch, asked everyone who’d registered to help with trail work, so I helped. He also needed help with setting up the website and marking the course. Next thing I knew, he and I were brainstorming an idea for a 50-mile and 50k race in that same area. We had a good partnership where we were good at different things. So, we started putting on these Capitol Peak races together,” says Varner, who became the co-director of the race series in January of 2004.

Then, he crewed Pearch at the Western States 100—and again, his world shifted.

“It was my first time going to a 100 miler. I was blown away with Western States—all the hoopla, tradition, and history. And I loved the idea of a point-to-point through mountains, through the night, through crazy conditions. All the fun of a 50k was dragged out in time. Mistakes were costly and rewards were magnified. That changed my racing trajectory from getting better at short races to being like, I want to be a 100-mile runner. Every year after that—up until last year, 2019—my annual goal was to do one 100 miler and all the rest of my racing and training would be geared toward that,” he says.

In September of 2004, Varner ran his first century distance, the Plain 100 Mile, and finished second place.

“Plain is famous for a super-low finisher rate. I was the seventh finisher ever. The race had been around about seven years at the time. The race course is not marked. There are no aid stations. You can have one drop bag at the epicenter of the figure-eight course, at mile 60. If you have crew, they can be there. You can’t have pacers. They normally don’t allow someone to do it as their first 100 miler. But the self-sufficiency appealed to me. I’d been doing two-day training runs where I’d run into the mountains with my sleeping bag in a pack, lay down and sleep, and run home the next day. I felt I was prepared for the challenges of the race,” he says, so Varner reached out to the race directors. They invited Varner to join for a training run on the race course. If he showed up and finished the run, he could register.

Varner biked to meet them at the trailhead (he still didn’t own a car) but miscalculated the distance. The ride took three hours. When he showed up, no one was there. He’d written down the route description, so he started running. Twenty-five miles later, he caught the group, kept going, and finished the 50-mile run a few hours ahead of everyone. “The race directors were like, ‘You biked here, figured out the route on your own, and you beat us by multiple hours. You can do the race.’ I was in a lot better shape back then. I was a farmer. I was doing heavy labor jobs and biking everywhere,” he says.

After the Plain 100, Varner visited his sister for Christmas. She’d moved onto Orcas Island, Washington. He spent a few days exploring the area including trail runs at Moran State Park, where his sister worked.

“When I stumbled on Orcas Island, it was so magical. I felt we had to organize a race there,” says Varner. In 2006, his dream of the Orcas Island race series lifted off and became the first official event of Rainshadow Running.

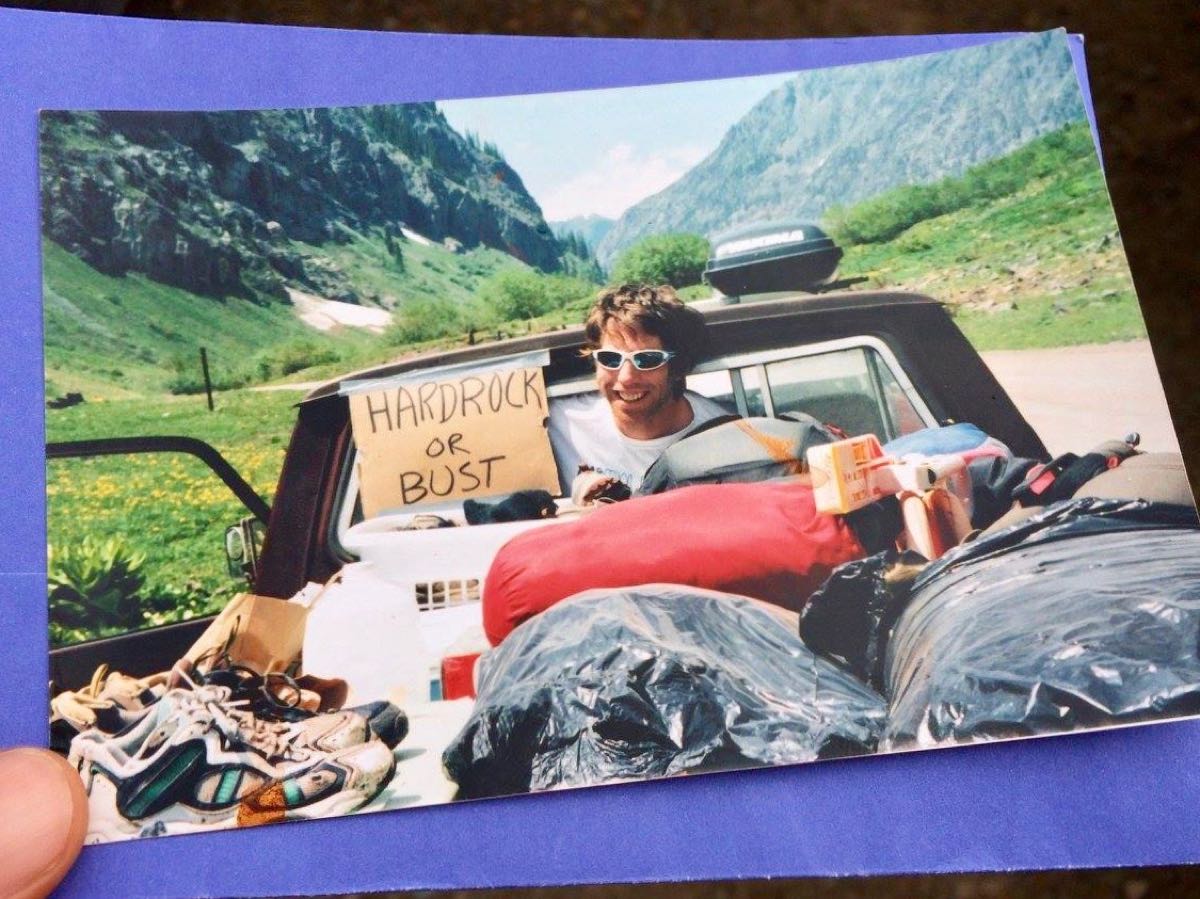

Varner was finding his path but wasn’t totally settled, yet. The next few years brought a number of adventures and moves, following at times the trails which inspired him. In 2007, this included a six-month stay in Silverton, Colorado. “I went out to run the Hardrock 100 [for the first time] and didn’t come back until Thanksgiving,” he says. It was an event that he’d return to run five more times over the next 11 years. After his inaugural Hardrock, he returned to Pacific Northwest and worked as a manager for a nonprofit doing stressful, labor-intensive work.

By 2009, he had established multiple races but was still working another job to make ends meet. He remembers, “A handful of the races I had were doing well. They were selling out and the sport was growing. I thought if I could make a little bit of money for 12 races a year, I could pay the bills and have an idyllic lifestyle. I could be doing something I love, sharing wonderful experiences with people, and I’d get to travel to these great places where the races are located. It was mentally an easy decision for me to make the transition,” Varner says. At the same time, “I didn’t have college loans. I didn’t have a family or a mortgage. I was basically a dirt bag. I didn’t need to make a lot of money,” he says. So he quit his job and doubled down on his race efforts.

In 2011, he had close to a dozen races lined up and was a full-time race director. Rainshadow Running now hosts annual races with various distances at 10 locations. “I was totally not sure but I gave it a shot, and so far it’s working out. It’s still a little nerve-racking,” Varner says. Fast forward to the present, where things remain nerve-racking, but now for a different reason. Before the COVID-19 global pandemic, Varner also had four employees. Unfortunately, he had to lay off his staff, which he hopes is temporary. He’s on lockdown at his home in Twisp, Washington, with his girlfriend.

“Coronavirus has been hard on everybody—our industry is feeling it right now. There’s been a major impact for Rainshadow Running. Our revenue has gone down very close to zero. We’re at five percent of what we expected for revenue. The little money we had in the bank account has to get us through until people have confidence to sign up for races again. And, no one really knows how long this will go on for. The situation is evolving daily. What works for one race company doesn’t always work for another,” says Varner.

Today, Varner is also the race director for the Waldo 100k. And he’s the course director for the Hardrock 100, as of 2019. “I’m just totally honored to help this race. It’s my favorite race in whole world for multiple reasons. It’s so beautiful there. It’s such a challenging course. My favorite thing is the people. Hardrock does an amazing job at every aspect of the race. I’m really lucky to be a part of it,” he says.

“In addition to race directing, Varner is the founder of the nonprofit Outdoor Arts & Recreation. Within the organization, he launched The Trail Running Film Festival, founded in 2013. The inaugural event was hosted alongside the Gorge Waterfalls Trail Races and sold out immediately. In March of 2014, they expanded the festival to include a 12-city tour in the Pacific Northwest followed by a 31-city nationwide tour that fall. Certain stops along the film-festival tour are huge, sold-out shows including in Boulder, Colorado and Portland, Oregon while others are smaller and more intimate.

This year, in light of COVID-19, he launched the first-ever “Virtual Edition” festival event to take place Friday, May 1. The evening will include a two-hour live stream of never-before-seen films and prize giveaways. The ticket price ($10) supports operational costs, but at checkout there is an option to add a donation to support the YWCA COVID-19 Emergency Relief and Community Resiliency Fund. At the time of this article’s publishing, the festival has collected more than $10,000 in donations.

“It’s a really fun idea that me and a few friends from where I live came up with to combine outdoor recreation and the arts. The big idea is to empower people and provide more opportunities for folks through programs—they could experience the arts and outdoors in fun, creative ways. We’re still in our infancy,” he shares.

Over the years, the sport’s growth has been positive overall, he says: “I love our sport. I love what it’s done for me and how it helps get people in the outdoors. It’s really good for our physical and mental health. And it’s really good for the planet, because the more people that experience the outdoors, the more likely they are to be come stewards. And now, there is a greater variety of races to choose from and they are creative.” There are tradeoffs to growth, too. “The impact that some races have on the environment, the overcrowding of local roads, and the mess left behind is the bad side of the growth. I’d rather see 10 races with 200 people than one race with 2,000 people. We always cap our races due to limited parking, limited indoor space, and fragile trails,” he says.

Overall, with so many responsibilities on Varner’s plate, it’s hard to train for his own races and run goals, he realizes. He’s DNFed a few races including Hardrock, which hits home for him. “I put on 25 pounds when I became a full-time race director, because I sit [at the computer] all the time. My own running is the thing that’s suffered the most over the last 10 years. When I commit to putting on an event—a film festival or a race—and have a time crunch, I choose work before my own racing or training,” he says.

In 2019, he scaled back a bit. He didn’t do a film-festival national tour, and took on a partner to split the festival work 50/50. “It’s hard to do it all. If I focus on one thing something else suffers. I end up working all night and not sleeping. Other times, I go on three-day running vacation and the work piles up. My goal moving forward is to figure out how to have all these things I want but to keep my sanity and to do a good job. One way I keep balance is by delegating. And with Rainshadow, my co-race director took over so much day-to-day stuff, so I was able to focus on the bigger picture,” says Varner.

On the horizon, he’s eager to focus on a few, huge missions he’s had in mind since he first attended the Annual Gathering of the Appalachian Long Distance Hikers Association in 1999. He dreams of FKT attempts on all or parts of the AT, Pacific Crest Trail, and elsewhere. Varner says he’s motivated “to go out and attempt things that are too hard for me, or there are too many challenges to overcome.” He may be more grounded now, but Varner is still reaching for the sky.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- Have you run a Rainshadow Running event? Leave a comment to share your story?

- How about racing, running, or adventuring with James Varner? Can you share an experience?