[Editor’s Note: This story was co-written by Sarah Lavender Smith and Meghan Hicks.]

On the second Monday of this past March, Maggie Guterl left her office at Tailwind Nutrition near Durango, Colorado, where she works as the company’s Athletes and Events Manager, to go for a run. But not a typical post-work run.

This would be a peak training effort for the notoriously tough and nearly impossible Barkley Marathons that was scheduled for sometime around the last weekend in March (the exact start time is kept secret, adding to the logistical and psychological challenge for competitors). The five-loop 100-mile race, combining treacherous conditions with orienteering, is so difficult and disorienting that only 15 men and no women have completed it since the race began in 1986.

She was approaching the 2020 Barkley—her third attempt after being timed out after a single loop in both 2018 and 2019—with characteristic determination layered with enhanced confidence earned from finishing first overall at last October’s Big Backyard Ultra, another infamously oddball race started by the same guy behind Barkley, Gary Cantrell aka Lazarus Lake. Maggie ran a 4.16-mile loop every hour at Big’s for 60 hours and 250 miles, becoming the last person standing and first woman in the event’s seven-year history to finish on top.

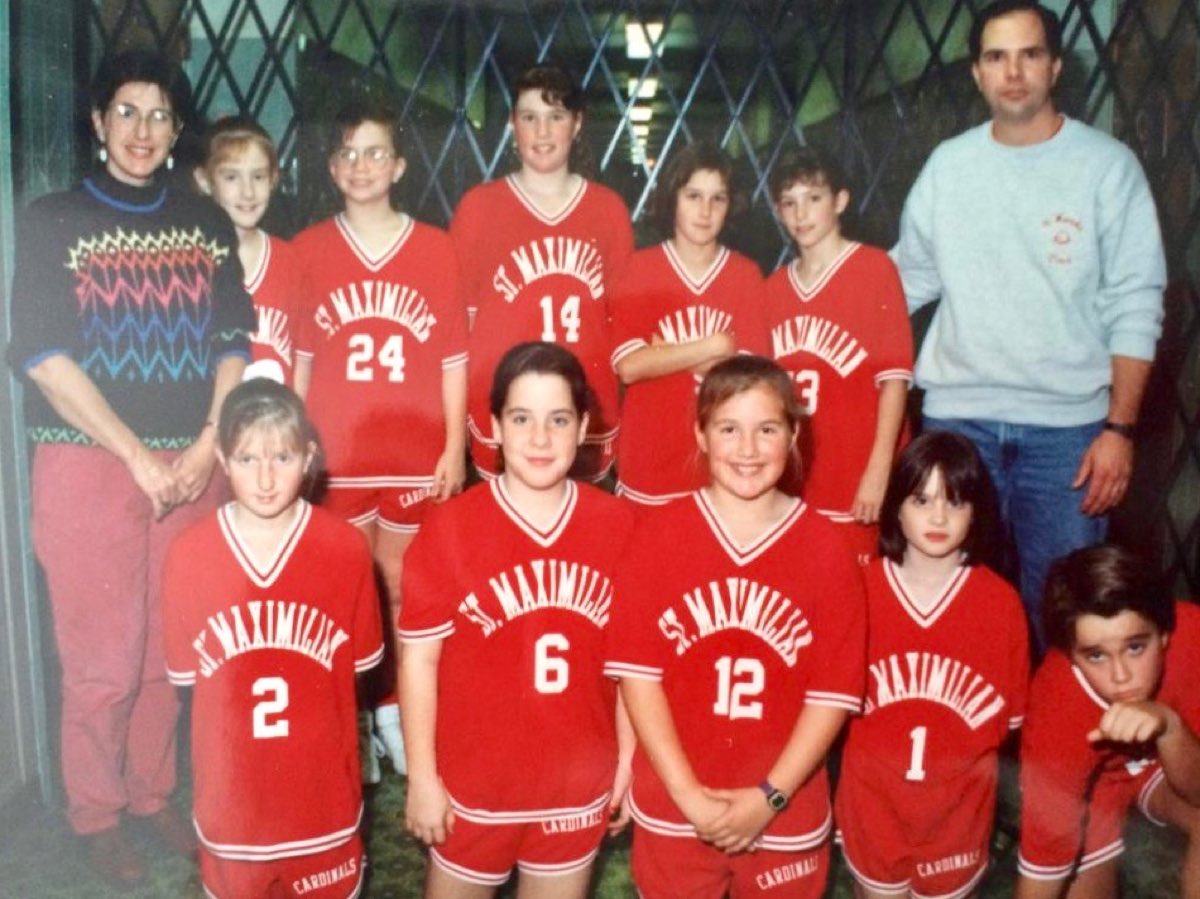

Maggie Guterl at the 2019 Big Backyard Ultra where she would become the last person standing. All photos courtesy of Maggie Guterl unless otherwise noted.

Maggie felt tired after work that Monday. She had staffed a mountain-bike festival in Sedona, Arizona for Tailwind all weekend long, running as much as she could after hours. The prior week, she had spent four days straight in Frozen Head State Park, Tennessee, training six to eight hours a day on Barkley’s terrain through frigid weather and dense fog, narrowly missing a destructive tornado that hit Nashville as she left Tennessee. She could feel the travel and mileage sapping her energy.

But feeling tired was good. Training while physically tired and sleep deprived would theoretically make her better prepared to endure Barkley, where she’d have up to 60 hours to tackle the five loops.

So after work, Maggie made her way to the short, brutally steep climb of what’s called the Hogsback in Durango to hike up and run down its dusty singletrack to the ridgeline, gaining 600 feet in just four-tenths of a mile. She summited the 7,400-foot ridge not just once, not a few times, but 18 times over an eight-hour period—past sunset, past midnight, stopping only because a case of bronchitis that had lingered since new year’s flared up and led to coughing fits.

“I was going to do 10 hours, and I was trying to rationalize that it was okay to [stop early] because of the hacking cough, she said. “I’m glad I did because it’s a pretty steep hill to go up and down for that amount of time. I think there needs to be some running in between,” she said matter-of-factly, as if the only thing strange about summiting a mountain 18 times after work is the lack of runnable flat stretches in between.

At that point in her training, roughly three weeks before the start of Barkley, her thoughts and actions revolved around two main things: Barkley, and work. “The days when I can do the training that I want and how I want it, it feels like, Yeah, I can do this! I can do well at Barkley,” she said the day after her Hogsback training run. “Then other days, it’s like, Oh, shit, it’s been five days since I got in a good workout. You try not to feel guilty, but I have to work, and my job demands a lot. It’s been really hard.”

She had no idea then that one week later, everything would change.

Maggie, like athletes everywhere, is now grounded at home because of the coronavirus pandemic. Barkley, like events everywhere, was canceled. And in a matter of days that unfolded mid-March, in an experience shared by individuals across globe, her focus, perspective, and routine transformed.

The week after that nighttime training run in Durango, “I was obsessed with watching the whole situation, trying to figure out what it meant for Barkley, and trying to figure out what our social responsibility was. Barkley is the least group gathering of any race [because of the small number of participants and remote location], but you still have to travel to get there, and people would have to leave their families for this. Who knows if we could even get home? It seemed crazy.”

Once Cantrell officially canceled the race because the state park revoked the event permit, she mainly felt relief. “By then, I couldn’t even imagine going,” she said. And instead of feeling sad about the loss of something she’d devoted so much time and effort to preparing, she thinks: “There are so many other bigger problems. And we have a year to train for Barkley 2021.”

For now, like people everywhere, Maggie feels in limbo and mostly isolated as she works from the home she shares with her boyfriend of five years, Ryan Schannauer, and their Weimaraner dog, Titus. As she logs daily runs, she can reflect on the strange, abrupt twist to a transformative year that began when she took the Tailwind job and moved from Pennsylvania to Durango in April of 2019–a year ago almost exactly. She also can nurture her goals of improving her performances at both Big’s and Barkley after she marks a milestone birthday of 40 this coming August.

“With all of these cancellations, most runners including myself will maybe find time to do other things,” she said. “We pack on so many races, but there are so many other adventures to try. I’m hoping we can have the freedom to move around, but it’s all up in the air, and I’m just trying to stay positive.”

Maggie (right) with Courtney Dauwalter (left) and Alicia Vargo at the 2019 Imogene Pass Run. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

From Bartender to 24-Hour Champ

It’s not uncommon to hear people characterize Maggie Guterl’s ultrarunning feats as extraordinary. “She’s utterly amazing,” says Holly Floyd, her friend of some 15 years who nudged her to start running back in 2007 when they both worked as bartenders. “She is just so determined, and when she does not feel she has reached the goal that she wanted to, it just makes her push even harder for the next.”

Maggie herself still finds her transformation to an elite endurance athlete somewhat hard to believe. She recalls a time in the mid-2000s, when she was a habitual smoker and heavy drinker leading a nocturnal lifestyle, “I came home super early in the morning and saw these people wrapped in mylar blankets and was like, Gross, they just ran a race.” She laughs, “I thought they were gross!”

She says she wasn’t sporty in high school or college because “I was more interested in ‘having fun.’ I just wanted to do my thing, hang out with friends, go to parties, and do whatever. Fun for me now is obviously totally different.”

Maggie grew up with one brother, 19 months younger, in West Chester, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia. Their dad worked as a chemical engineer and mom as a journalist and editor. Her parents always have been supportive of her interests, she said, and although her dad was a runner, he didn’t push her to run. “He ran half marathons when I was a kid,” she says, “with cotton crew socks and short shorts!”

Maggie viewed herself as an artist, not an athlete, and attended Pratt Institute in New York from 1999 to 2003 to earn her Bachelor of Fine Arts with a major in Illustration. She started bartending in New York while a student in 2001 and kept at it for eight years, moving back to Philly to bartend from 2004 to 2009.

After getting off their shift in Philadelphia, Maggie and her coworkers would hit a bar down the street where Floyd, a single mom, worked in the early hours of the morning, and the two women struck up a friendship. “We’re both a little sarcastic, and she was just a fun and funny person to be around,” says Floyd.

Floyd recalls that Maggie looked similar back then in her mid twenties, “she’s just a healthier version of her former self. Since our work life led to late nights, not the healthiest of diets, and more alcohol than water, we all could have looked a little better and taken better care of ourselves.”

It was Floyd who got the idea to try running first. “I had decided I wanted to be a healthier person and start running, and Maggie was like, ‘Okay, I’ll do it too.” The two women started showing up at numerous 5ks held around Philadelphia and working up to the 10-mile Broad Street Run. “She just naturally had the speed, and it didn’t matter how she felt arriving at the race,” Floyd says, “she just ran it and ran it fast. I’m not sure how many times she placed, but I’m positive she did, on a few hours’ sleep and a cheesesteak from the day before as nutrition.”

After that promising start to running in 2007, Maggie recalls, “I wanted another goal so I signed up for the 2008 Philadelphia Marathon, but my training went to shit and I wasn’t focused.” She ultimately skipped the race.

In 2009, at age 28, Maggie decided to change for good. “I was feeling kind of lost,” she remembers. She left bartending and weaned herself off the late-night lifestyle and cigarettes that went with it, and she took training to become a certified personal trainer. She worked for a time at the Philly Sports Club “until I realized this wasn’t for me and it was pretty hard to make money in that profession unless you started your own business,” so she went on to work for a real-estate company for about five years.

Most significantly, she refocused on the Philadelphia Marathon and set a goal to finish it in 3:30, to have a cushion for her then Boston Marathon qualifying time of 3:40. She ran it like clockwork in 3:30:06.

From that year on, Maggie viewed herself as a health-conscious runner and became more goal-oriented. “I have to have goals to keep me on track,” she says.

Her friend Floyd speculates, “Her energies had to be directed somewhere, and running was it. Her transformation as a runner came from her transformation as a person. When we met, we were living the service-industry lifestyle. … Once she left that environment, she got healthier and stronger. There was a time for Maggie when she didn’t see anything worth achieving, so once she did, she literally ran with it.”

Floyd’s description couldn’t be more precise. Within a little more than a year and a half, Maggie went from marathoner to an ultramarathoner racing for 24 hours at the 2011 Back on My Feet Lone Ranger, where at the age of 30 she put in a respectable 97 miles. Not too shabby for one’s first ultra, but Maggie had set a goal of running 100 miles in those 24 hours.

“I really thought it was doable to make it 100 miles. It was but nutrition is hard,” remembers Maggie. “I wallowed in misery and couldn’t deal with the nausea, a lack of experience, you know. Had I got my ass moving a little sooner, I would have had time for those last three miles. I was running pretty good at the end.”

Says Floyd, “Her determination during that run, and disappointment with missing 100 by only a few miles, only drove her to put more into her training. She just kept striving to do better and push harder, and it has brought her to where she is now.”

The log of Maggie’s early ultra years on UltraSignup reads as perfectly regular for a budding and enthusiastic ultrarunner, lots of races and distances with some performance hits and a few misses. But then the records change, starting with her running 142 miles in a day at the 2014 New Jersey Trail Series One Day. It was a national-class performance for 24 hours, and it landed her in first place overall. On paper, it’s a breakthrough performance, and she agrees, “It showed me that maybe I could do things I’d read about other women doing.”

A Running Life Develops

In 2014, Maggie enlisted professional help with her athletic development in endurance and fitness coach Michele Yates, who owns Rugged Running. Over that time, Yates says she’s helped Maggie develop in pretty much every aspect of running, including strength, nutrition, overall cardiovascular training, and mobility.

But Yates says there’s one thing she’s never had to coach Maggie on: “attitude. She is determined, she has grit, she has the ‘it’ factor…. She won’t stop at anything. She will give you a run for your money if you are competing against her, and even if she kicks your butt, or you kick hers, she is a great sport. She’s a person you want in your life.”

That same year, longtime boyfriend Ryan Schannauer–and his dog, now their dog–Titus arrived into her life. Explains Maggie, “I was moving out of Philly and back to the ‘burbs.” She says that she was finally done with city life and training so much on the pavement. She continues, “We would meet to go trail running and that’s also when I met Titus! He was Ryan’s dog but now he loves me best. He is the best dog I have ever known.”

In 2015, Maggie started working for Nathan Sports, first in customer service and then in marketing.

A health-focused lifestyle, committed training and a coach guiding it, a partner with the same outdoor hobby, a job in the industry, and plenty of mental strength: running had become a part of every aspect of Maggie’s life. And this focus showed in her results over the next half decade.

Among her top results during this time period was a fourth place at the 2015 IAU 24-Hour World Championships, where she was the third scoring member on the team-gold-medal-winning Team USA. The race did not come easy for her, though. “The first half was a total sufferfest due to nausea and vomiting. In the second half, I had to fight hard as it was a team race, too. So how bad I felt didn’t matter, and [the team competition] made it easier to run hard for 12 more hours after a crappy first 12.”

In 2016, she set about qualifying for the Western States 100 by earning one of the coveted two entries offered to the top finishers at the Georgia Death Race. She earned that entry and took her East Coast fitness west for eighth place at Western States.

Maggie (left) on her way to eighth place at the 2016 Western States 100. Connie Gardner is pacing her.

That same year she ran an incredible 14:47 at the Brazos Bend 100 Mile, improving her time by some two-and-a-half hours from her previous year’s performance. She was pretty stoked on this run, too, “I had a goal and didn’t achieve it the first year. Then I came back and smashed it the second attempt.” Indeed, she smashed it. Her time is the third-fastest a woman has ever run for 100 miles on the trail in North America. Maggie’s status as a top female American ultrarunner was sealed with 2016.

Amongst all these stellar performances and like any good ultrarunner, there were a few misses too. She sums things here up well, “[My boyfriend] Ryan calls me a ‘stubborn asshole.’” Though she may be feeling or performing poorly, she’s got a history of pressing on to finish. Among these character-enhancing runs was her 10th place at the 2017 Run Rabbit Run 100 Mile. “I barely made it to mile 40 and was so nauseous I couldn’t eat. My crew wouldn’t let me quit and I needed a Hardrock 100 qualifier.”

And somewhere, amongst the highs and lows, the seed for the simply ridiculously long and hard ultramarathons was planted. In typical Maggie style, it was pretty early on. In 2015, she finished the Barkley Fall Classic 50k, a tempered-but-still-tough 50-kilometer race on the same terrain as the Barkley Marathons.

The year 2018 was her debut at the grandmomma Barkley Marathons. She timed out on loop 1, completing it after the time cutoff. By now you’ve probably realized that this would not dissuade her, however. Later that year, she tried the Big Backyard Ultra for the first time. She put in 183 miles and was the second-to-last woman standing. And, yep, that only encouraged her on as well.

It was also at this race where the friendship between her and eventual last woman standing Courtney Dauwalter was fully forged. Says Dauwalter, “We’d met through messaging on Facebook before we actually met in person. I was doing a 24-hour race early in 2017, and asked for some tips on how to improve at this format. Maggie was on the U.S. 24-hour team and had a really successful day at the 2015 IAU 24-Hour World Championships, so I wanted to pick her brain on how to pace them better…. I was in awe of her and couldn’t believe when she messaged back. It felt like I was talking to a celebrity!”

On race day(s) at Big’s, Maggie and Dauwalter teamed up to share resources and good energy. Explains Dauwalter, “What’s that saying? A rising tide lifts all boats? … Maggie and I help each other be better. We went into it with a plan to help each other. We were going to share our supplies, share our crew, and encourage each other to keep going through the tough times. We didn’t plan to run together as running our own paces seemed like a smarter strategy. Once the race started, though, we fell into an easy stride together and that was that. We ran side by side for almost two days!”

After Maggie dropped from the race, Dauwalter would run on for another day and 100 miles to finish as the event’s runner-up. “Maggie became another member of my crew,” recalls Dauwalter. “She barely slept after her nearly 200 miles, and then took on the role of cooking warm food to eat, helping me wrap my head around continuing on, and just being there.”

The Last Person Standing

If everything until this point in Maggie’s story represents steady progress upward, then what happened next has to be considered a giant leap that started with a cross-country move and ended as the last person standing.

In April of 2019, Maggie and boyfriend Ryan Schannauer, plus Titus of course, packed up their Pennsylvania life and headed west, bound for southwestern Colorado where Maggie took on a new job at Tailwind Nutrition.

This, says Maggie, changed entirely the way she recreated. With the high-altitude San Juan Mountains at her door, the summer of 2019 became summer of adventure. She admits it was a difficult transition, even for the super-tough East Coast trail runner. “It was really hard at first,” she says. “I just have to expect to not see those same numbers I see at sea level anymore. I thought maybe they’d level out, but it doesn’t; it never feels super easy to go up a hill [in Durango’s high altitude]. But I definitely think [the altitude] helps my endurance overall.”

Maggie with Cody Reed after the pair won the 2019 Silverton Alpine Marathon in Colorado. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

Her summer in the Colorado mountains sure did help her endurance. Fast forward to October of last year when the now 39 year old finished as the last person standing at Big Backyard Ultra, her second attempt at the event. This time, she put in 250 miles over 63 hours and outlasted the 71 other participants, which included nine other women and 62 men. She was the first woman to win the event outright in its seven-year history.

Colorado ultrarunner Gina Fiorini was one of Maggie’s 2019 Big’s crew members. About Maggie’s race, she remembers, “I have crewed several endurance events, but never have I seen someone so determined and dead calm. If Maggie was ever suffering or upset, she never let that on. At one point she just flat out said, ‘I don’t see this ending any other way (than winning).’ It gave both [fellow crew member] Jenn Coker and I chills.”

In asking Coker, an ultrarunner also based in Colorado, what was memorable about crewing Maggie, she, too, points to that moment. Continues Coker, “Maggie joked around before the race started about being ready to go 400 miles. As time went on, you could see she really meant it.”

Maggie confirms she’ll give it another whirl this coming fall–that is, if we’re back to racing by then. “I want to see how far we really can go…,” she hedges a bit. When pressed on if she’s got tangible additional goals for an event at which she’s already succeeded, she responds, “Well, yeah, the 100-hour goal is always there. That goal would be really hard to achieve. But to get to 100 hours would be so cool.”

Because of their history and set-up, gender is a persistent issue at the Barkley Marathons and Big Backyard Ultra. Everyone has an opinion, so what does Maggie think? Does she feel extra pressure to represent her gender well? What was it like to outright win Big’s? “Yeah, that was cool. I mean, the race has been going on for seven years, so not super long, and I feel there’s no doubt a woman definitely could win it….”

Maggie, like others, have postulated what she can do when she returns in 2021 to the Barkley Marathons for the third time. “It’s definitely motivating,” she says of the quest to be the first woman to get a Barkley finish. She says she’s focused mainly on accomplishing three loops for a 100k ‘fun run’ finish there, and then seeing if she can go farther. “I think a woman can finish, but I’ll feel more like that when I’m going into my fourth lap. It’s been a while since a woman got a ‘fun run’ so I’m really hoping to get at least that.”

All that said, there’s a year to go between now and then–and a whole pandemic creating a 2020 of uncertainty. One certainty among this is that Maggie will turn 40 this year. “It’s a little weird to be a master’s runner, but people freak out about it…. I’m hoping to do more mountain stuff, getting more backcountry experience, and maybe doing thru-hiking-type things. … I tried my first backpacking experience last summer. Hopefully in 10 years I’ll be like, Look at all these cool activities I have besides running.”

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

Pennsylvania, Colorado, and beyond runners, have you run or raced with Maggie Guterl? Leave a comment to share your story!