When treating an injury–running-related or not–the four fundamentals of healthy joints must be addressed:

When treating an injury–running-related or not–the four fundamentals of healthy joints must be addressed:

- Full range of motion. Restore normal range of motion to joints, tendons, and muscles. Full mobility equals maximum blood and fluid flow in and out of tissues.

- Strong, supportive muscles. Restore normal muscle activation and strength, not only to the specific injury, but all around it.

- Be normal. Efficiency is everything. Most injuries are the product of too much (volume and intensity) on inefficient loading. Using joints, limbs, and systems in their maximum-efficient way is crucial to performance and recovery. Conversely, inefficiencies stress tissue. Even worse, pain tends to create compensation, which can perpetuate and even worsen inefficient loading. Efficiency is the most important but most frequently overlooked or glossed-over element of injury recovery.

- Don’t overdo it. All tissues have a limit of activity. Individual tissues, like an athlete, have an element of fitness. Sometimes they can handle enormous loads (like running a 100 miler), but very quickly that tissue tolerance can dissipate, and the same tissue can only handle a 10-minute walk. Just as a runner gradually ramping up mileage, knowing one’s specific tissue tolerance and not exceeding it is vital for improvement without a flare-up.

Successful and swift recovery from all injuries requires this comprehensive four-dimensional approach, and constant (if not obsessive) diligence toward all four elements throughout the rehabilitation process.

Why Running Injuries Don’t Get Better: The Halfway Approach

When a runner is injured, it is too common to address only one or two of those four. On one end, orthopedic professionals–usually a (non-runner) doctor–will prescribe absolute rest, then a gradual return to running. However, upon doing so, the runner’s injury pain returns. Why? Because both doctor and runner failed to address mobility, strength, and efficiency.

On the other end, diligent athletes and their fitness-minded physios will exhaustively exercise–stretching, strengthening, drilling, icing, elevating, compressing, and bracing–yet quite often, they, too, recover very slowly. Why? Because they neglected the other two elements.

They overdo it, with either one or more:

- Running too much

- Running or cross-training too intensely

- Over-stretching or over-strengthening sensitive tissue

- Doing too many non-running activities (usually including weight-bearing)

Along with overdoing it, the athlete and physio also tend to overlook efficiency. They fail to take a fine-tooth comb to all things gait–not only running, but also walking. Inefficiencies tend to cause injuries; pain-induced compensations tend to perpetuate or even worsen them.

As you can see, the hardest of the two elements is being normal (efficiency) and not overdoing it (tissue tolerance). The more efficient you are, the more sensitive tissue can handle; conversely, injured tissue has a very poor tolerance to inefficiency, including limping and compensation. Then, sensitive tissue requires some tissue loading, but not too much. Just how much loading is required is a ‘Goldilocks dilemma’–what’s too hot or cold, versus just right? Devising a progressive activity plan is as much art form as it is evidence-based protocol.

Plantar Fasciitis and the Four Fundamentals: Easier Said Than Done

Plantar fasciitis is one of the most common and persistent injuries affecting runners, particularly trail runners, who must negotiate challenging and punishing terrain. It has been written about so many times that while most runners know of scores of treatment techniques, few are able to quickly extricate.

Perhaps it is because those techniques address only strength and mobility, neglecting efficiency and activity?

Personally, I have had all sort of foot and ankle aches and pains, including several episodes that I would consider to be not plantar fasciitis, but other issues of muscles, tendons, and joints in the foot. But just recently, I have been lucky enough to experience true plantar-fasciitis injury for the first time. It fooled me, because I thought it was a simple tendon soreness, or some stiff foot and ankle joints. I was mistaken. My simple heel and arch soreness progressively worsened, and the classic medial base-of-the-heel pain appeared. It is sore to pressure, weight-bearing, and aches with too much activity.

Plantar-fascial strain, like the Achilles, can be difficult to heal because it is essential weight-bearing tissue with relatively poor blood flow. Once strained (or microscopically torn), it can be very painful and slow to heal.

As with every injury, it was a terrific learning opportunity and application of the four fundamentals. For plantar-fasciitis treatment, tools and strategies abound for mobility and strengthening. But what about efficiency and tissue tolerance? Once again, I return to a clinical pearl gleaned from my boss and mentor, Jeff Giulietti, “No limping allowed! Be normal until it is sore, then rest.” It seems simple, but this concept is extremely challenging. What is normal? What constitutes limping or compensation?

Normal, efficient walking and running utilizes the whole foot, from heel to toe, and from outside to inside. For walking, especially, a heel-to-toe gait is vitally important. That rocker allows for normal walking forces to disperse along the entire foot–as opposed to a toe-walker or forefoot runner where the forces are concentrated on the front of the foot, adding greater stress to the plantar fascia.

But if you ask anyone with serious plantar-fascial pain, they’ll be quick to tell you:

- It’s very painful on the medial heel and arch

- Putting direct weight on that area is both painful and frightful (“Walking directly on it will make it worse… right?”)

Therefore, they will consciously or unconsciously avoid weight-bearing in that area, either through toe-walking and/or excessively lateral striking–both with walking and running.

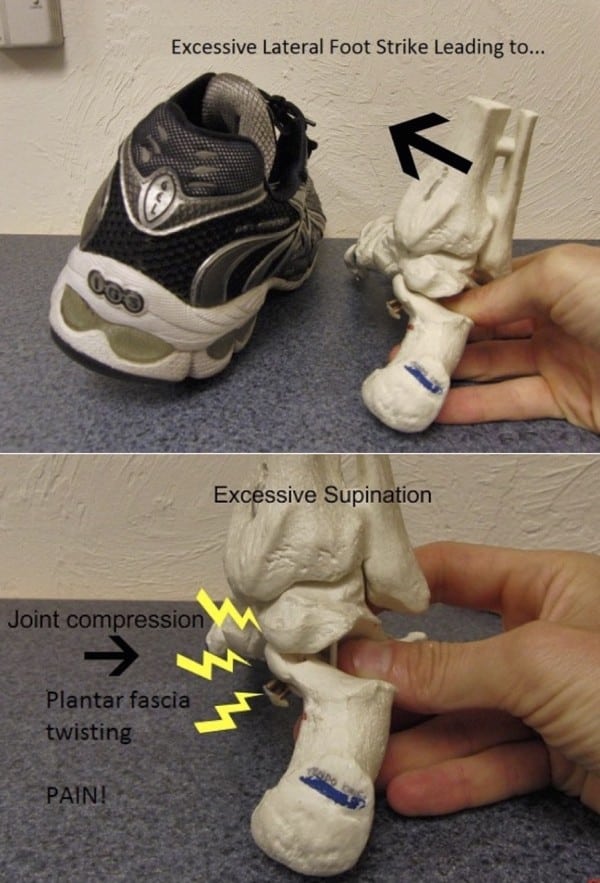

But what strategy, normal or forward/lateral, actually stresses the fascia greater? First off, excessive lateral striking to avoid a medial pain makes sense, but as discussed in the previous foot pain article, excessive lateral striking adds energy to the system. The foot collapses from a greater height, while adding greater twisting stress to the plantar fascia, as the forefoot eventually slams to the ground, twisting the fascia along the way:

A photo illustration from the first plantar-foot pain article indicating how an excessive lateral strike creates more impact stress.

To consider heel-versus-toe striking, I had to dig into some classical physics. Torque is the cross product of a force times the length of the lever arm. So the resultant rotatory energy is greater with a longer lever. If you’ve ever used a wrench, this is easy to understand. The longer the wrench, the easier it is to turn a bolt.

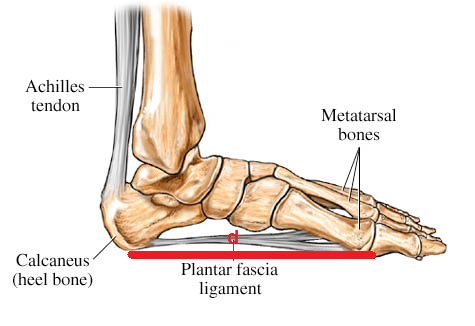

With the foot, the injury site for the plantar fascia is its insertion at the heel. So it stands to reason, that the more force applied farther away from the heel–with the fascia as the lever–the more stressful force is applied to the injured fascia! This is illustrated below:

Model of the foot with plantar fascia. Fascial length and lever arm is indicated in red, with distance d. Image courtesy of WebMd.com, amended by Joe Uhan.

As you can see, with a forefoot strike, the lever arm (red) is long:

Fascial loading with a forefoot (walk or run) strike. Note the long distance of the red lever with a forefoot strike, in relation to the heel bone, where the fascia inserts–and the typical location of the strain. Image courtesy of WebMd.com, amended by Joe Uhan.

But with a heel strike, the force arm is much shorter, at least five times less:

Fascial loading with a rearfoot strike. The length of the red lever with a heel strike, is far shorter, resulting in significantly less torque applied to the sensitive insertion point. Image courtesy of WebMd.com, amended by Joe Uhan.

So even though it may be tender to step directly on the sensitive insertion, the avoidance forefoot strike places as much as five times greater load to the fascial insertion point!

This may still be difficult to grasp: How can walking directly on the tender heel be less stressful than avoiding it on the forefoot? The answer is another question: What is more stressful to a strained rubber band, stretching it lightly or to its maximum?

Step on It… Then Rest! Tackling Plantar Faciitis Head-On

The best overall strategy for healing plantar fasciitis is truly a four-dimensional approach. To review:

Full range of motion. Massage and stretch the fascia and surrounding tissues, without overdoing it. (Of note, most braces and overnight socks vastly overdo the degree of stretch. Morning tightness is usually due to over-stretching and stressing the fascia the day before.)

Strong, supportive muscles. Strengthen all muscles of the feet and calves.

Be normal. Address both walking and running efficiency. Walk and run heel-to-toe. Or at the very least, to ensure you’re not unknowingly over-stressing the fascia, make sure you’re employing a relaxed, midfoot run technique! Run whole foot, and avoid excess lateral striking. In the big picture, be sure you’re not running asymmetrically, overloading one leg, as identified in a previous article.

Here’s another big issue: Relax! Protective tension can play a major role in perpetuation of pain and dysfunction. Runners will commonly–yet unconsciously–keep their foot stiff with walking and running as a way to protect the sensitive tissue from stretching. This short-term strategy may be helpful in the acute stage to limit over-stretching. But over time, keeping the foot rigidly tensed during gait is akin to driving the car with the parking brake on. It needs to be free to move!

A healthy foot should be relaxed but athletic–flexing and extending as part of the walk and run cycle. When returning to running, err on the side of being too relaxed, letting the foot feel floppy–so long as you strongly push-off behind, a la Elite Feet!

Don’t overdo it. Walk and run with max efficiency for as long as you can, then rest. This means stopping at or just before the moment the heel begins to ache. Achiness during or after running, including just walking and standing around, indicates the tissue needs rest. Getting off your feet for as little as five to 10 minutes may be enough to allow you to bear weight again. Avoid flare-ups, which include any activity resulting in more significant pain or swelling. This means you’ve vastly overdone it, irritated the tissue, and possibly reversed healing.

There are some taping techniques–such as the Low-Dye Technique–that can help unload the sensitive fascia. A cursory search of this term online will yield some how-to articles and videos, but this technique is best reserved for a skilled medical professional.

***

Every day and each run is a learning experience, and the art form behind successful training and racing is the same as healing: the balanced recipe of the right ingredients in the right quantities. Let pain be thy guide, but above all else, be normal and efficient as long as you can, then rest! Then, the next day, do just a little more.