From Gina:

Before we get this conversation going, let’s make sure everyone knows what a pacer is.

Pacer: A person who accompanies a racer to provide motivation, assistance in keeping on a racer’s goal pace, and in a rare few circumstances, to mule the racer’s gear. Historically, pacers have been permitted by race rules in races 100 miles or longer in length. There are a few 50-mile and 100k races that allow pacers as well.

Pam, Liza, and I have all competed in races with pacers, have had pacers, and have played the role of pacer. Experiencing each side of pacing, we understand the importance behind this role, the effects that a pacer has, and the duties one must fulfill.

Though it may seem pretty straightforward, playing pacer isn’t always as simple or easy as it sounds. It can be much more than just going for a jog with your friend. Pam and Liza, what are a few qualities and duties you expect from a pacer, and what are key things you both do when pacing?

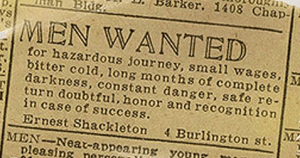

Mythical Ernest Shackleton ad for his Antarctic expedition.

From Liza:

I feel like I’m writing a Shackleton follow-up ad.

PACER WANTED

for hazardous journey, no wages, bitter cold (or maybe extreme heat or bone-soaking downpours), long hours of complete darkness, constant whining, safe return your responsibility, runner will enjoy honor and recognition in case of success.

Liza Howard 2 Oak Grove dr.

If I had more money to spend on the ad, I’d tack on:

- Willing to give the shirt off your back. My first 100 miler took a lot longer than I expected it to (no surprise there), and I got very cold in the middle of the night. My pacer took his long-sleeved shirt off and gave it to me to put on over my top. He literally gave me the shirt off his back. That’s the kind of dedication I’m looking for. Chris is 6’8″ and I’m 5’1″, so we were an interesting-looking pair coming into the aid stations. Chris said afterward that he would have done a lot more sit-ups and some tanning had he known he’d be half-naked for a good three hours in the middle of the night.

- Skill with vomit. I returned a pacer’s hat once with: “Sorry, I think I got vomit on it.” She didn’t blink. And my buddy and longtime pacer, Brian, managed to come up with a different and encouraging comment over 30 miles of retching at Leadville one year. “I bet you feel better after that.” “Wow!” “Good job missing your shoes on that one.”

- Can carry on an interesting one-sided conversation. I don’t have any extra words left late in a race, so a pacer who can chat happily for hours without any response from me besides a grunt or a nod is worth her weight in gold. I once learned the origins of the nicknames of all the Colorado mountain runners. Miles disappeared. Gossip is appreciated (especially if I can keep my soul clean by not commenting.)

- Thick-skinned. I say: “Please stop talking for a little while.” You say: “Sounds good!” You think: Nothing. You just stop talking.

I used to think the best pacers were best friends. That’s who you’d want with you when your soul was bared–and maybe your butt was exposed. But I met two of the best pacers I’ve had during a race. Sometimes luck brings a kindred spirits your way–selfless talkers with thick skin and a facility with vomit.

Ultimately though, races allow pacers because they’re supposed to help keep runners safe. So, at the very least, a pacer must:

- Know when to take charge. “Take off that wet layer at the next aid station–including your sports bra–and change into dry clothes.” “Try getting a bit of this gel down. Now!”

- Know the course. “That’s a game trail. Do not head off into the dark woods on a game trail.”

- Know the distances between aid stations. Pacers should make recommendations about gear and food when their runner’s ability to do math and plan for changes in the weather is impaired.

Looking over it, I’m not sure why anybody in their right mind would answer this ad. Thankfully, most of my friends are ultrarunners. ‘Nuf said.

From Pam:

When it comes to choosing a pacer, I think a lot of it is personal preference. I have had the pacers who tell endless stories about their past or dish lots of gossip. But I find that when I am past the point of upholding my end of the conversation, I am also past the point of focusing on what the other person is saying and the constant chatter becomes irritating to me. Like Liza, I do want my pacers to do their homework and have some familiarity with the course and the location of aid stations. I also really like it when I feel like my pacer is invested in my personal goal and wants to help me achieve it, rather than someone who just wants to get in their own training run. I assign my pacer to be in charge of all the ‘meet and greet’ sessions on the trail–making the small talk and saying nice things when we pass or get passed by other racers (because I want to do those things, I just don’t always have the capacity to do it!), so this is something I try to do when I am pacing for other people.

One important thing to note is that sometimes the person with whom you have chosen to spend your life (or another loved one) is NOT the best person with whom to spend the tail end of 100 miles. My husband Mac is a great guy; he’s super supportive of my running and he makes me laugh. When it comes to crewing, he is top notch. But he has paced me in two 100 milers and neither one was marital bliss. The first time around he was a little too invested in my race. It was the final stretches of the Western States 100 in 2011 and I was in the critical 10th place. We knew that Helen Cospolich in 11th place was gaining on us, and so my husband decided he needed to implement a hill-interval workout up to Robie Point: one minute run/30 seconds walk. As the trail got steeper, I couldn’t keep it up, despite Mac warning me, “You aren’t getting passed on my watch!” I broke down in tears and finally he relented and let me go at my pace. Fortunately, I finished F10 by a narrow, four-minute margin.

After a three-year pacing hiatus, Mac decided he’d like to do a short, seven-mile segment with me in the middle of Angeles Crest 100 Mile. I know Mac was only trying to help, but he kept telling me to eat during a time when I wasn’t feeling that great. About halfway through I got really grumpy and said something along the lines of, “Stop nagging me about eating! It’s really f—ing annoying. I’ll eat when I get to the aid station!” He ran the rest of the way in silence and hasn’t paced me since! (Can you blame him?) Fortunately, after a root beer and some cookies, my blood sugar was up and I was much more pleasant for my second pacer. Well, at least I didn’t cuss her out! When I nearly puked on Mac at the finish, I think he became a bit more sympathetic to my suffering and we are still happily married!

Three-time Bighorn 100 Mile (and now the course-record holder as of last weekend!) and Angeles Crest winner Ashley Nordell also cautions against automatically choosing your spouse as a pacer.

“As much as I appreciate my husband Josh being willing to run 52 miles with me, I have found I perform better for friends. Josh can tell me to pick up the pace, and my response to him could be an earful of not-so-nice suggestions right back at him. “How about you try running faster at mile 85, huh?!” When a friend tells me that it’s time to go, while I might be cursing him in my head, I will be far likelier to respond and listen. If Josh tells me to eat a gel, I’ll list the number of times I puked in the last 10 miles and then have a pity party for myself and my terrible 100-mile stomach. If a friend pacer tells me to eat, I’ll at least pretend to do so. I think it comes down to a level of comfort. Josh knows me so well that I am well beyond caring if he sees me laying down in the middle of the trail attempting a nap or throwing up for the 10th time. Whereas for a friend, not only am I conscious of that fact that they are stuck out there as long as it takes me to finish, I want to try to seem like decent company.”

Some people do really well with a loved one as a pacer, but it doesn’t work for everyone. Your loved one may have a hard time seeing you suffer and may not be able to give the tough love you need to get you to the finish. Additionally, it is easier to say exactly what you are feeling to a loved one and this can result in you having a pity party and pouring out all you emotions, or like in my case, taking out your suffering on them.

Of course, there are some times when it is nice to have your life partner by your side in a race. I was really glad to have Mac by my side to celebrate one of my first big wins at the Miwok 100k in 2011. And Ashley notes that when things get really bad, being with your favorite person can help, “I have had races such as Bighorn one year where I got so sick for so long that I was relieved it was Josh with me because I think anyone else would have been scared to keep pushing me on due to the issues I was having. Josh knew me well enough that despite how bad things got, he was comfortable enough to urge me on to the finish. I don’t think I would have wanted someone else to have to have been there for those 50 miles.”

From Gina:

Liza and Pam have most of the main points covered, but the one thing that I can add is making sure your pacer is skilled at motivating and is well versed as a ‘people reader.’

Katie DeSplinter Grossman and Krissy Moehl were my two pacers at Western States in 2015. Both had been following my progress as I passed through aid stations and had watched things slowly roll downhill. When I arrived at Michigan Bluff, my clothes were soaked in sweat and ice water, and I was chucking everything I attempted to swallow. Feeling helpless and obviously upset, Krissy suggested a do a total reset. This meant changing into fresh dry clothes, reassessing food choices, and reigniting motivation.

When I picked up Katie at Foresthill, she had funny stories already picked out and ready to go, but she also had many motivational statements in her bag of conversational tricks. Telling me stories was one thing, but interjecting little positive and energizing statements was the key to keeping me in a good headspace and moving forward toward the finish.

With both of my pacers being able to assess my situation and produce solutions, they helped me get to the finish line. I normally don’t like people telling me what to do, but in this instance I was so happy to be ‘bossed’ around. Their ability to make my decisions for me and having energizing trigger statements queued up helped me get to the finish line.

Now that Liza, Pam, and I have provided some examples, lists, funny stories, and cautions, you should have a pretty good visual of what it takes to be a pacer, and what is expected. Here’s a refresher:

- Positive energy, no matter how bad things can get.

- Thick-skinned. Runners can get cranky and sometimes say things they don’t mean.

- Aren’t easily grossed out.

- Selfless.

- Cautious of pacing loved ones. It will either work great, or you will be arguing for hours.

- Know your racer, what they can handle, what they can’t, and what their triggers are.

- Be able to make quick decisions for the racer when they aren’t able to.

Remember to take pride in helping racers achieve their goals, and also in helping them make hard decisions when things may get dangerous. And, although this job may seem intense, tiring, and at times yucky… it is a key piece to your racer’s success.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- This seems like a totally appropriate time to share some hilarious pacing stories. Leave a comment and give us your best ones of you either as as runner or pacer. What was so funny about the situation? What was the ultimate outcome?

- In all seriousness, what are some of the things you’ve learned that work and don’t work in pacing and being paced?