I have written about heart-rate physiology and training before in ‘Stay the Course.’ While heart-rate training has been the gold standard of exercise prescription for decades, it continues to come under scrutiny from trail ultrarunners, and more notably from some of the sport’s most prominent coaches, who believe that heart rate is too highly variable to be a reliable training guide. I think they are wrong, and here is why.

I have written about heart-rate physiology and training before in ‘Stay the Course.’ While heart-rate training has been the gold standard of exercise prescription for decades, it continues to come under scrutiny from trail ultrarunners, and more notably from some of the sport’s most prominent coaches, who believe that heart rate is too highly variable to be a reliable training guide. I think they are wrong, and here is why.

Heart-Rate Basics

What it is.

Heart rate is a form of biofeedback that correlates to physiological workload. The theory is, the faster the heart beats, the harder the system is working to provide the system with the required physiology–water, oxygen, and nutrients into tissues; and carbon dioxide, acid, and byproducts out of tissues.

How it’s measured.

Most modern GPS running watches come with either a chest or wrist heart-rate monitor, which uses either electrical or optical technology to measure pulse rate (in beats per minute). Late-model heart-rate monitors can often read erratically, especially the early generation wrist monitors. But the technology is improving and the readings are increasingly accurate.

Why monitoring exercise physiology matters.

Most runners and coaches agree that optimal fitness requires training different physiological–or energy-utilizing–systems. These systems include:

- Anaerobic alactic— This is a short-lasting system that delivers energy for tasks under 10 seconds. It uses leftover energy that is sitting around in the muscle cell. It does not require oxygen–and does not produce byproduct waste–because it is already produced.

- Aerobic— Fat metabolism, where the body uses predominantly fat as fuel, is the desired energy system. Always. For everything. The reason is that fat metabolism is a more efficient, less stressful physiological process than glucose (or glycogen, or exogenous sugar) metabolism. In fact, a key metabolic byproduct of fat-burning, β-hydroxybutyrate, acts as a protective shield against cellular damage.

- Anaerobic lactic— This fast-acting, oxygen-less energy system utilizes glucose sugar only. While it is fast acting and highly powerful, it is also extremely stressful. Cortisol hormone, a pro-inflammatory stress hormone, is released in significantly greater amounts during higher-intensity, sugar-burning exercises. Other pro-inflammatory waste products include lactate and hydrogen ions (creating a more acidic cellular environment), and pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Optimal fitness development is the art form of balancing the slow-but-steady aerobic and powerful-but-stressful anaerobic systems. And because these energy systems run on a mixed continuum, precise monitoring of energy systems can be complex and difficult.

Energy-System Selection

Energy-system selection is based on far more than speed and distance.

A major error made by runners and coaches is the assumption that only training load impacts energy-system selection. In other words, they believe that training intensity and duration, alone, impact the degree of aerobic and anaerobic systems are activated in the body.

This is incorrect, because the body has other concerns besides the length and pace of your run. It has to balance the demand of your run, in addition to the other demands and threats it perceives outside of running, in order to keep you alive! And this is a tougher balancing act than most realize.

Exercise energy selection is feed-forward, not just feedback. Conventional physiology theory is that we are reactive species: we exist, we do something, our bodies react. This represents a feedback operating mechanism.

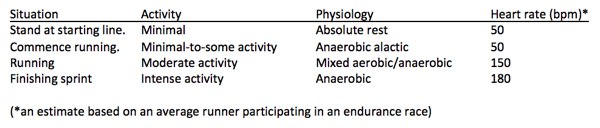

So for running, a feedback response would be:

But the key to optimal performance, and the key to human survival throughout our species’ evolutionary history, has required a system dramatically faster and more responsive than that. A feed-forward system is a system that tries to anticipate our needs far before we need them!

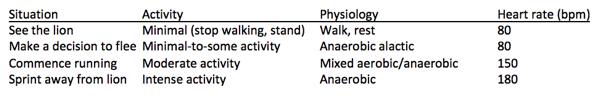

Consider this scenario: we are walking through the jungle and a lion crosses our path.

Under a feedback mechanism, the following would occur:

Does this mechanism seem like a sound survival strategy? Seems a little sluggish, doesn’t it?

What happens instead is a pure feed-forward mechanism. The micro-second brain processing of the sight of the lion instantly activates all energy systems, including the anaerobic system, into full force:

- High heart rate (up to 180 beats per minute within a few seconds)

- Heavy breathing

- Maximum neurological and metabolic activation of extremity muscles, in order to flee

Then, we get the hell out of Dodge!

This represents a feed-forward mechanism: the body (via the Central Governor, the executive of all physical activity) deciding how to act, far before we take that first step! This means that energy systems are activated before we even use them.

So those times when we think we see a lion (or perhaps a rattlesnake on the Western States trail), but are mistaken, we jump away, startled. Only moments later, when the conscious brain kicks in, do we stop fleeing. But as we’ve all experienced, the system remains activated (pulse rate, heavy breathing), at least for a short while.

This is the law of survival, the reason we’ve outrun the lions, tigers, and bears all these generations. The anticipatory feed-forward system is the law the dictates the vast majority of our exercise physiology.

This same design occurs during running, but usually to a far-more-subtle degree. The body can become relatively hyperactive, due to a number of factors besides the actual running pace. In fact, any potential stressor that the body deems relevant to survival–stress, fatigue, illness, the environment–may potentially change what energy systems are activated in any given run. It all counts!

The Hidden Costs of the Energy False Alarms

Thankfully we’re not always running from lions, but our bodies often behave that way. Life throws us many false alarms. Consider this analogy:

The alarm rings at the fire station. Without hesitation, the firefighters reacts. A score of men quickly but precisely assemble, dress, organize, load onto the truck, and blast out of the station.

Have they yet seen the flames or felt the heat? Not at all. They activate based on their perceived necessity signaled by the alarm. So when they arrive at the prescribed address, only to find only a small brush pile burning–or perhaps no fire at all–is there a cost associated with their activation?

Despite the false alarm, a finite and significant amount of resources have been preemptively spent: water, gasoline, even the calories ingested and burned by the firefighters in the preparation to battle the anticipated blaze. All the systems were activated and, while some of them may be put away, unspent, there is a sunk cost to that summons, and it is significant.

This is the mechanism of the day-to-day human stress response. Our fight-or-flight system often activates without any actual demand. When we get ‘stressed out’–engaged in a heated argument, mulling over a burdensome worry, or simply sitting in traffic–seldom is any physical task being undertaken. But the body is being activated. The engine is revving higher and tremendous sugar–the preferred fuel of fight-or-flight responses–is burned when under psychological stress, which is a major factor in ‘stress eating!’ We function as if we’re fighting an intense battle.

Therefore, when runners and coaches claim that factors impacting heart rate such as stress, environment (temperature, humidity, allergens), anxiety and nervousness, and caffeine and other stimulants do not elevate heart rate in a way that’s significant to the body’s physiology, they are mistaken.

Stressed out and going for a run? Your body will perceive the cost of that run as higher (because it is already dealing with your life stress) and will activate a more intense energy system to cover all the demands. More energy cost!

Anxious and nervous before the big race or workout? The Central Governor will recruit a more intense system to ensure your survival. More energy cost!

Experiencing allergies? Allergies like pollen represent an added immune-system threat, and the body will recruit more energy to overcome them. Again, more energy cost!

Taking caffeine and other stimulants? These artificially amp the system. Yep, more energy cost!

Think about your big race? Your heart rate–and total physiology–will amp up, because parts of your brain believe you’re actually racing! More energy cost!

These factors cause fire dispatch to signal a five-alarm fire for a given run on Long Run Lane when perhaps only one or two alarms were necessary. It’s because the dispatcher is sending extra engines for the smaller adjacent fires on Stress Street, Anxiety Avenue, and Allergy Alley! That those extra resources weren’t fully deployed to the run is irrelevant to the system. That higher energy system was activated and whether you ran hard or not, the fuse was lit and there is a cost to that deployment.

When the brain perceives a threat–real or not–a more intense energy system will be activated regardless of your actual running effort! You may not have punched out your boss during that heated argument, but your heart, lungs, nerves, and muscles are ready just in case! Likewise, when it is hot, humid, or the air is pollen-strewn, or you’re tired, stressed, anxious, and strung out, the energy cost is higher for the same running pace in ideal, relaxed conditions.

Elevated heart rate is seldom aberrant. It signals the entire body is ramped to another level of intensity to handle the added threats. More threats, more energy. More cost.

This means that your eight-minute pace at 160 heart rate–adversely impacted by the environment, anxiety and stress–has very nearly the same cost as your 6:30 pace at 160 heart rate under ideal conditions.

It all counts!

The Fallacy of Rate of Perceived Exertion in Trail Ultrarunning

Most coaches use Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) as a guide for exercise intensity. It is based on a scale developed in the early ’80s to help quantify perception of effort. The early studies of RPE were based on controlled studies of subjects exercising… in monotonous environments: treadmills, usually, but also exercise bikes and (if lucky) outdoor tracks.

Running, on the other hand, is extraordinarily variable. Ask any runner the mental difference between a flat pavement run amongst rush-hour traffic versus a solitary jaunt along the high-country ridges of the Western States 100 course. The same physiology may feel much different in different physical and psychological circumstances–and this is a huge factor in trail ultrarunning.

Because RPE is ‘perceived’ by the brain, enjoyment–and myriad other psychological factors–heavily influence RPE, including:

- Surroundings. Beyond physiological activation, the physical environment of our run may play the largest role in determining RPE. A beautiful, sacred landscape has immeasurable dampening effect on RPE.

- Community. With whom we run impacts RPE. Runners in a group tend to run significantly faster, with a lower RPE, than solo runners. This is the primary reason runners train and race intensely in groups. It’s simply easier.

- Context. Running in special areas–either in parks, or in historic trail races like Western States–can also dampen perceived exertion. If it’s special, it’s different. And easier.

- Variability. A major factor in perceived stress is monotony. Conventional road and track running has far more mental and physical monotony. The latter tends to facilitate joint and muscle mechanoreceptor activity sooner, and more intensely, signaling the brain that the run is more stressful. Conversely, the highly variable terrain of a trail run often seems less physically taxing, while it often (due to technicality or vertical) is more straining on tissues.

- Addiction Behavior. For better or worse, trail ultrarunning is a draw to addictive personalities. While the long, slow runs through nature are therapeutic, the extremes of time and distance can be a form of self-medication. Addictive personalities have significant difficulty finding and maintaining moderation in both volume and intensity, making RPE a poor choice for this population.

- Illusory Superiority. There is a tendency for individuals to believe they are ‘above average.’ This concept, called illusory superiority, while psychologically helpful, makes our own perceptions of ourselves a particularly poor metric of physiological reality. As such, we tend to think that either things are easier or harder than they really are. When self-assessing effort, we tend to:

- Rate an low-to-moderate effort is easier than it actually is (judge a 140 beats-per-minute run as a 2/10 rather than a 4/10)

- Rate a moderate-to-high effort as more difficult than it actually is (judge a 170 beats-per-minute run as an 9/10 rather than a 7/10)

This is evidenced in research on RPE versus heart rate in highest-intensity exercise, where subjects frequently rates themselves as working significantly harder than their actual physiological measures.

The take-home point is that individuals are poor judges of their own efforts and abilities, and this is magnified in trail ultrarunning where myriad factors dampen perceived intensity. Indeed, this may be why trail ultrarunners have a significantly higher incidence of burnout and overtraining syndrome.

The difficulty in assessing training and racing effort is a compelling argument for the utilization of a skilled ultrarunning coach. However, when coaches fail to employ a reliable metric for effort beyond RPE, not only may they fail to prevent the injury and burnout, they may unknowingly promote it.

A Coach’s Inconvenient Truth

As coaches, it is our goal that our clients run fast and far. Our livelihoods depend on it. So anytime a factor presents itself that prevents fast running, we coaches wish to eliminate it. When coaches endeavor to use heart-rate-based training, only to find athletes having to run (or even walk) excessively slow, that becomes unacceptable. It must be wrong, they think, as it makes no sense why a runner cannot complete their usual six miler in 50 minutes, because their heartrate is 20 beats higher than usual.

But to outright dismiss heart-rate data and go purely based on ‘feel’ or ‘usual pace’ is to potentially thrust their athlete into an entirely different training zone than desired. Additional variables–often measurable only through heart rate–can potentially transform an easy recovery run into a progression tempo run!

And when an athlete is performing an entirely different workout than desired, there are several implications:

- The coach and athlete can no longer accurately determine cause and effect from their prescribed workouts. This is because these workouts were not completed as intended. Clients ‘running easy’–at times of difficult-to-measure personal and environmental stress–might actually be running threshold pace. And ‘high-end aerobic pace’ might actually be VO2Max pace.

- A failure to differentiate between types of running efforts negates the value of having a coach. If a coach, in executing a training system, fails to precisely apply and measure aspects of the system, he or she then has no idea if their system is responsible for a runner’s success, if and when they are successful, or conversely, if their system–and not the individual runner–is responsible for a client’s failure.

So now what? If the myriad factors impacting heart rate all count in fitness development, then how do we balance it all?

Tips for Navigating Heart-Rate Training

Heart-rate training has its difficulties, and it is too easy to become psyched out in a closed-loop cycle of ‘negative information, negative mood.’ For tips on how to deal with these and other issues, refer to this resource. Here are some other tips:

Get tested.

To find optimal zones, get your exercise physiology tested in a professional, clinical setting. University research facilities are most trusted, as they use their equipment frequently to conduct research, using well-trained staff. Your next-best choice is a private center that specializes in metabolic testing. While most folks are hung up on VO2Max (the amount of oxygen the body is capable of processing), what is of more importance is:

- Easy aerobic zone (a zone of high fat burning)

- Maximum aerobic zone (the zone just before fat metabolism declines precipitously)

- Lactate threshold

Armed with these correlated zones, you now have a most precise heart-rate ranges with which to work. Some testing facilities will also correlate these zones to treadmill paces. However, this has poor application to the trail ultrarunner who seldom runs on flat, windless treadmills. A heart-rate zone is ‘portable’ for whatever terrain, elevation, and environment you run.

Accept that non-running factors impact physiological cost.

Once you and your coach accept that it all counts, then you’ll recognize the importance in addressing non-running factors. Running and life are not separate containers. What happens in life invariably impacts running. Addressing and balancing life factors such as stress, sleep, nutrition, and environment (temperature, humidity, allergens) will keep their impact on physiology and heart rate minimized, thereby optimizing fitness.

Objectively measure fitness gains.

Fitness does not mean faster. Any runner can train to do more simply by learning to push harder. Pushing harder is not fitness–it is extraction. Fitness is one of two things:

- Higher performance with the same effort

- The same performance with less effort

The only way to track true fitness gains is by having a metric. Heart rate is the most useful and easiest metric to track true fitness gains, wherein running faster per heart rate, or running the same easy pace at a lower heart rate equates to true fitness gains. Otherwise all you may be doing is learning to push yourself harder, which–while crucial to peak performance–is an eventual dead end of plateau, injury, and burnout.

Find Ease: ‘The Absence of Hard Does Not Make it Easy!’ and the Endorphin Argument.

This is an oft-quoted line to my clients: that just because a run does not feel hard, does not mean you are training at a low intensity. In fact, if a run feels really good, you may still be running too intensely.

Why do we have endorphins? An evolutionary theory is that endorphins blunt the perceived strain of physical activity, so that we do not stop. When running away from the lion, had we stopped because of pain, we would have been killed, and our genetic material would not be passed on. Those who experienced endorphin release during painful, stressful exercise survived.

Therefore, endorphins may exist to blunt the perceived damage and stress of moderate-to-high intensity effort. This means, in order for endorphins to be released, the brain must perceive the effort to be at least moderately stressful.

Conversely, if your running effort is truly easy, few endorphins will be released! Big buzzkill, but this is a common theme amongst my clients where truly easy runs:

- Feel extremely effortless

- Often feel less good than workouts because of the total lack of endorphin release

If you or your coach do not wish to use heart-rate zones, then easy running bouts must feel truly–and unequivocally–easy. They should feel effortless, and at times less comfortable than moderate- or high-intensity workouts.

Listen Closely.

The whole point of a heart-rate monitor is not to restrict our behavior, but to enlighten and educate through biofeedback. But the most superior biofeedback is developing the ability to listen to our bodies. Tune in to its subtle or not-so-subtle messages:

- Taking full, deep, relaxed breaths, breathing (partially) through your nose is a hallmark of easy, aerobic effort.

- The presence of absence of ‘effort burn’ in your legs and lungs will help discern between easy and hard.

- If you find yourself bonking during training runs, this represents a deficit in aerobic effort, or state of being.

Exercise physiology and the science of endurance training can be nauseatingly complicated. But perhaps it can be simplified to a conversation I had with Bruce LaBelle, one of trail ultrarunning’s founding fathers and who is–now four decades later–still out there running in the mountains.

When I asked him about balanced training and the key to running longevity, what he said was, “I train like my dog: he runs hard all day out there with me, and when he comes home, he does nothing but eat, drink, and sleep for a few days, barely moving, until he’s ready to go again.” That’s a funny thing coming from a career research chemist. And, silly as it may seem, this is the philosophy that has allowed LaBelle to continue to run the ultradistances–and continue to get into the mountains on the regular–into his sixth decade.

Perhaps it is that simple: listen to your body. But the demands of a runner’s life and those other things that tug at our heart strings can sure make that difficult. The heart-rate monitor is merely a tool to tune in: not just to the run, but to the totality of our lives.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- Do you train with a heart-rate monitor according to certain zones?

- How often do you find yourself successfully running by ‘feel?’

- Can you ever feel the effects of non-running stress on your body when you are out training?