So far in this coaching column, I have stressed the importance of planning. I think it’s critical for runners to develop mantras, plan out their aid stations, and work on their rapid-relaxation skills. In this article, I take a different approach, one that acknowledges the unpredictable nature of the real world. By way of a personal narrative (1), I want to explore the topic of changing training plans. This is the story of a difficult mid-workout decision that I had to make recently, right before my first big race of 2020. I hope that by reading about my experience, you can reflect on similar decisions that you may have had in your own training.

My fingers and toes were burning cold as I trotted up Manitou Avenue in Manitou Springs, Colorado, near where I live. The storefronts and shop windows were dark in the early morning light. A few slabs of hard snow and ice lingered in the shadows, but the sun was rising bright and strong.

I’ll be warm soon enough, once I start up the Manitou Incline, I thought.

I passed the Manitou traffic circle and jogged uphill toward the base of the Incline. My feet tapped the ground as I glided over ice and concrete.

Maybe I can get under 20 minutes today? My workouts have been good. My legs feel weird, though. How is that possible? I took yesterday off! That was my first full day off in a couple of months. I’m probably just cold still.

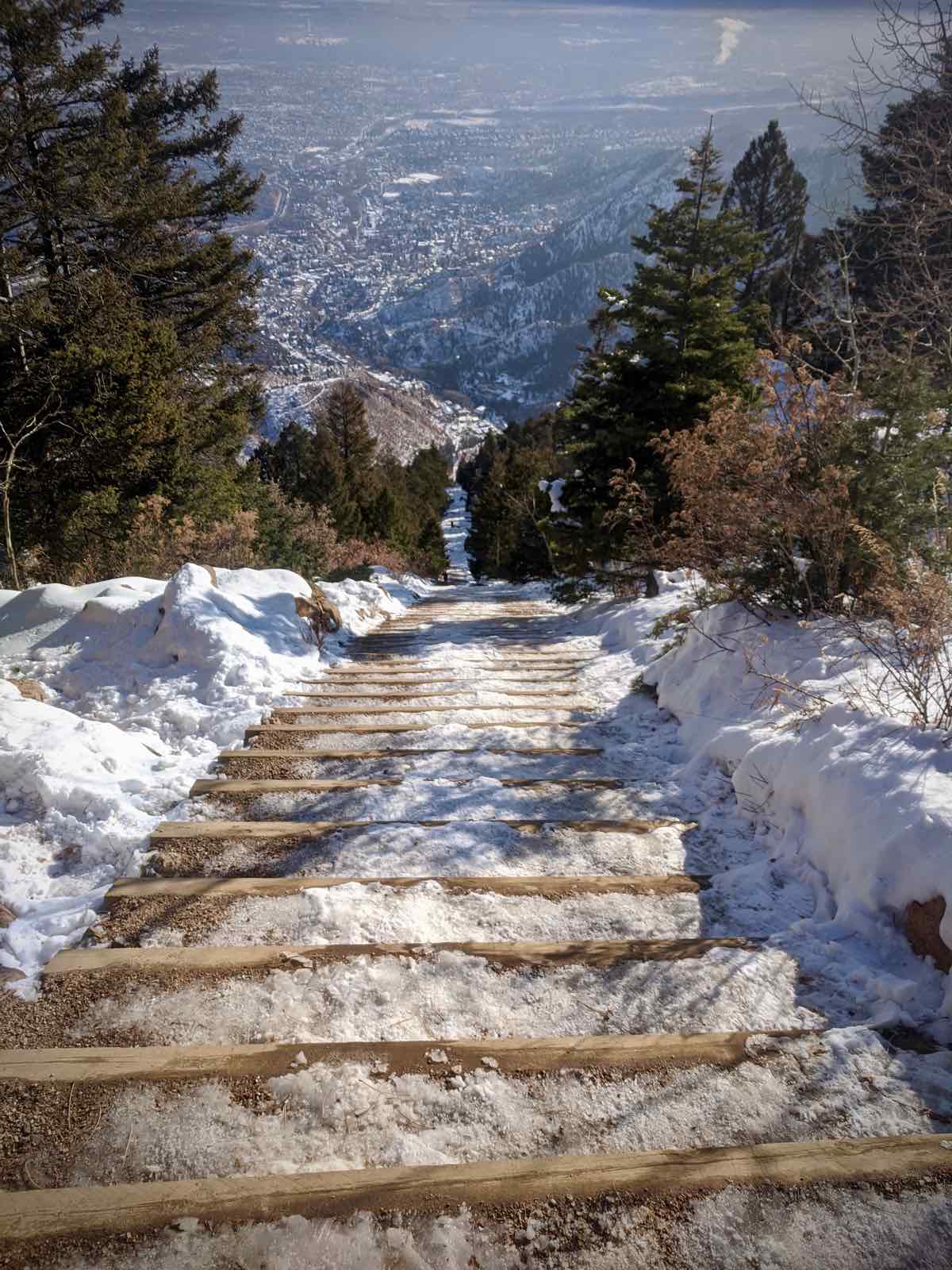

I had previously spent hours reviewing my training log to figure out what combination of workouts and rest days had been ideal for tapering in the past. I pored over the details of my most successful tapers and created what I hoped would be a perfect taper plan for the 2020 Bandera 100k. This taper would be the same as what I did before the Run Rabbit Run 100 Mile, Hong Kong 100k, and Black Canyon 100k, which were all very successful races for me. Now, I had one last workout: a hard effort up the Manitou Incline, a 2,000-vertical-foot climb in less than a mile. After that, I would really rest for the next three days until race day.

What is wrong with me? I think my legs are pumping acid instead of blood. It’s okay, I’m still warming up.

I hit the final road uphill before arriving to the base of the Incline. I decided to walk this section to let my pounding heart settle. Instinctively, I went straight for a port-a-potty to postpone the inevitable pain I was about to experience. Once inside, I sat there and put my face in my palms. My breathing wouldn’t settle as it should.

It’s fine. I’ll feel better once I get going. I’m sure I can still manage something under 22 minutes. That would be a nice confidence boost. I know I’m in good-enough shape for that. I ran under 22 minutes a couple of weeks ago.

I hit the split button on my watch, and with a mechanized chirp, I was off. Two steps at a time, moving fast, then one step at a time. Slower, but still running. I passed tourists who gasped in surprise.

Here we go. Keep it in control. My legs are flat but I can still make this a good workout.

A third of the way up, I was breathing like a steam train. I took a walking step, then ran again. Then I walked more. I glanced up at the endless cascade of stairs ahead of me. They looked steeper and longer than ever before.

Holy crap, this hurts. Why aren’t my legs moving? I’m supposed to feel effortless right now. Maybe I rested too much? That workout last Saturday was good. But now it’s Tuesday and I’ve barely done anything since then. I must be out of shape by now.

I settled into a slow trudge. No more running, not even a step. Sweat dripped down my face and burned my eyes. It felt like the sting of the blood coursing through my quadriceps.

This is stupid. I’m five days out from a 100-kilometer race. I don’t need to be running an all-out uphill effort right now anyway. I need to be smart. This must be my body trying to tell me something.

I stopped, took a deep breath, and gathered myself. I looked around and noticed that I was one of the few people on the Incline that day–a rarity! The air was warming in the rising sunlight. I took off a layer, drank some water, took a photo with my phone, and continued on with a new mindset.

This is the right choice. I’ll keep it easy and not make my legs feel any worse than they already do. So what if my body isn’t reacting the same way to this taper like it has before? Today is today, and this is how I feel right now.

As a coach and athlete, I’ve realized the importance of changing daily plans. I spend a lot of time and effort creating training plans for myself and for the athletes I coach which contain a process that is designed to stress, recover, and improve the athlete. I’m confident in the final product and excited to see improvements occur as the plan progresses. But sometimes during that process of planning and executing, we lose track of our humanity. We are not machines, and a plan on paper, no matter how thoroughly researched, will never know us as we know ourselves. As I realized that day on the Incline, training plans don’t always line up with how we feel.

Magness (2) explains that it is crucially important to think beyond the isolated effects of a singular workout, and instead think of what the “global effects” of that training might be. In my case, I failed to understand the impact my workout from the previous Saturday had on my body when combined with the mental stress of returning to work on Monday after a winter vacation. The two days of recovery that I had planned between those Saturday and Tuesday workouts may have been enough for me in a normal week, but the added life stress was something that I had not accounted for.

When I finally accepted the fact that my legs were not responding to the taper in the way that they had before, I made the mid-run decision to change my plan. At that moment I was thinking beyond my planned workout and considering the global effect of the training. Even though it was extremely difficult for me to do at the moment, I knew that I had to deviate from my ‘perfect’ taper plan in order to actually achieve my goal of reaching the start line healthy and rested.

I’m as guilty as anyone when it comes to getting caught up in an ideal training plan. I sometimes fail to remember how important the global effects of training are, and instead worry about how a single missed workout will ruin my fitness. There is real pressure to achieve certain numbers like weekly training volume, pace, and elevation gain. Those numbers can feel like they determine the value of a training cycle. However, when the bad days come, I try to ask myself a couple main questions. The first, and probably the most important, is to determine a run’s goal. Each run we do should have a specific purpose. If we can’t execute the run the way that we need to, it’s a sign to change the plan.

In this story, my run was supposed to be my final sharpening and confidence-building effort before my big race. When I realized I couldn’t complete the run as planned, I was faced with the next question, which is how I would work around the setback. Sometimes this means taking an extra easy day to recover, and then trying the workout another day. Or sometimes, like in this situation, it means skipping the workout entirely because it interferes with the global plan.

I made it to the top of the Incline without checking my time. The day that I thought would be the pinnacle of my training block turned out to be an easy day on the trails. I am so glad I changed the plan. After feeling that level of fatigue built up in my legs, I knew I needed to rest. I only ran a couple more times before toeing the line at the Bandera 100k that weekend. As a result, I felt well rested and went on to achieve my goal of earning a Golden Ticket to the 2020 Western States 100. And now, as I start to sketch out my training plan for Western States, I can reflect on this experience, understand that things don’t always go to plan, and accept that a single bad day doesn’t derail months of training.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- When was the last time you needed to change your run midway through it? Can you explain the circumstances? Can you also share how your mid-run thought process went?

- Have you ever completed a run according to plan when you probably shouldn’t have? When your body was telling you it needed something different for the day? Can you share a retrospective of what happened and what you learned?

References

- Jones, S. H., Adams, T. E., & Ellis, C. (2016). A History of autoethnographic inquiry. In Handbook of Autoethnography (pp. 84–106). Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

- Magness, S. (2014). The science of running: how to find your limit and train to maximize your performance. San Rafael, CA: Origin Press.