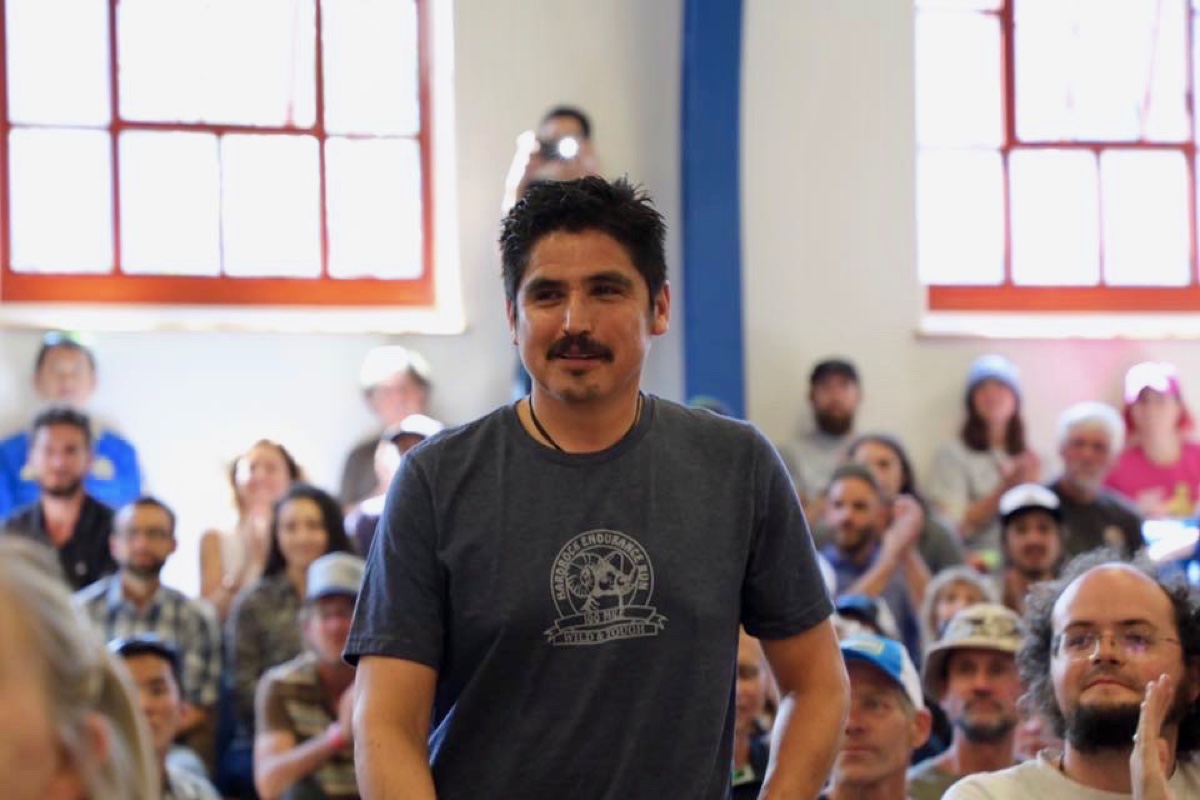

With genuine elation, Noé Castañón jokes that he’s a slow ultrarunner and that he’s truly indifferent to the speed at which he finishes his races. What’s most important to him instead is an unwavering, unapologetic commitment to train and complete each event. And perhaps equal to that is his commitment to supporting the running community which has given so much to him.

In truth, Castañón is not your average endurance athlete.

Castañón lives in El Sobrante, California, a city of 13,000 residents located about an hour north of San Francisco. Despite long rush-hour commutes, he works in Oakland as an auto mechanic. He’s worked at the same shop for 23 years and continues a career he started decades ago in his home country of Mexico.

A dual U.S.-Mexico citizen, Castañón was born and raised in central Mexico in his hometown of Fresnillo, located in the Mexican state of Zacatecas. He grew up in a household of 10 kids and was raised with traditional Mexican values, which he describes as meaning shared family meals, an important focus on chores and homework, and practicing the Catholic religion including Sunday church.

Castañón learned about San Francisco long before he immigrated to California. His father lived in San Francisco during the 1950s, and when his parents married in the ’60s, in Mexico, Castañón’s father largely remained in the U.S. for work. He owned a lucrative landscaping business throughout Castañón’s childhood. Castañón’s mom was a housewife in Mexico and raised the kids more-or-less alone while his dad economically supported the family. His dad traveled back-and-forth to visit them all.

Then, in 1987, as his dad steered his way back to Mexico for a home visit, he had a fatal car accident. Castañón was 17 years old.

“When a drunk driver killed my dad, that had a huge impact in my life. That’s one of the reasons I don’t drink. After that, there was too much suffering for our family. My dad, the provider, was no longer there. We had to start over. But we stayed together,” he said. He’d graduated high school at 15 years old and was attending college in another city for his automotive-mechanic degree. As a full-time student, he also worked. After his father passed, he doubled down on hours to earn a wage that would cover his living costs in full, including books, rent, and food. His siblings all got jobs, too, to help support their family. Each week, Castañón took an entire day to travel to the post office, where the closest pay phone was located, so that he could call home and touch base.

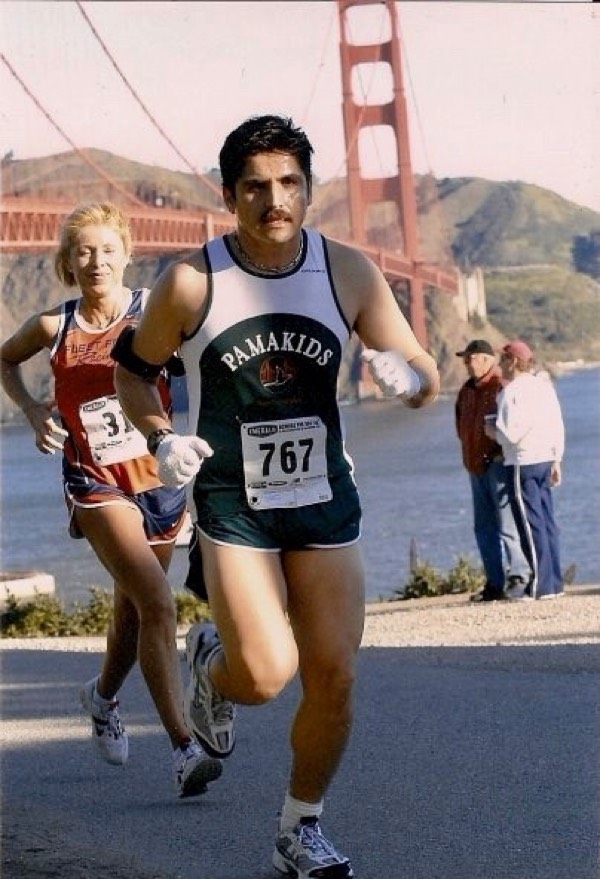

Close to a decade later, Castañón himself moved to the Bay Area—where two of his brothers had already relocated—in 1995. Back in the mid-90s, trail running in Mexico was pretty much nonexistent, he said. It was in California that his love for running sparked, in 2003. A friend invited Castañón to spectate Bay To Breakers, a race with more than 70,000 participants. The runners were so diverse—all ages and sizes—and he was stirred by the idea of their individual motivations.

“I felt embarrassed with myself. They were all trying something for themselves and I wasn’t trying anything. I thought, Next year, I want to be here, no matter what. It took me one year to train. That was my first-ever race, and it changed my life. I wanted to be healthy. Before that, I was a couch potato,” Castañón said. He says that wasn’t overweight, but that he was out of shape. After he started running, he shed a few pounds and the active lifestyle made him feel stronger and happier than ever.

In the months that followed, he ran 5ks, 10ks, and road marathons. Three years later, in 2006, he ran his first ultramarathon at the Six-Hour Distance Classic via loops in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. He covered 36 miles. “I said, ‘Wow, I did six hours? Next I’m going to run for 12 hours.’” Castañón was attracted to the challenge and novelty of ultras. The more he ran, the greater in love he fell with the process of training and racing. In 2007, he participated in the San Francisco One-Day 12-Hour Race, and the next year he ran on the event’s looped course for 24 hours. That year, he completed 85 miles.

“Some people think that running loops is boring, but I think it makes you mentally stronger. It’s very easy to quit on loops when you get tired. But if you focus on getting it done, you’re pushing yourself, and you can get it done. That’s not boring for me. That helps me to compete in other [even-harder] events—those races when mentally you don’t feel good but you need to keep pushing,” said Castañón.

In 2010, Castañón ran his first 100-mile race, the Tahoe Rim Trail 100 Mile, and finished in 31 hours and 34 minutes. Since then and to date, he’s participated in thirty-five 100 milers, including three appearances at the Hardrock 100. His inaugural 2012 Hardrock holds his PR: 45 hours and 52 minutes. When he ran Hardrock in 2015, he finished with four minutes to spare before the 48-hour cutoff. He’d spent that spring healing a calf injury, which put him on crutches and sidelined his training for an entire month. He couldn’t start other events he’d planned to participate in as he healed. When he toed the line for Hardrock, many people called him crazy.

“I was chasing cutoffs but wanted to finish and I did. I was so happy to arrive at the finish line with my Mexican blood. I got a lot of messages from Mexican runners who were excited that a Mexican was in Hardrock. It inspired other Mexican runners to start doing 100-mile races,” he said.

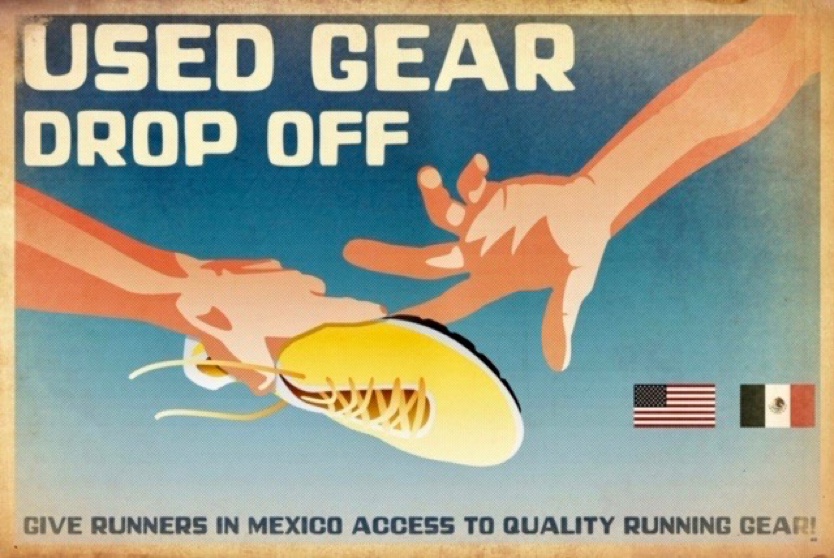

The sport of ultrarunning is still nascent but growing in Mexico. Though, the Mexican run culture doesn’t yet have the history of training, industry, or access to gear that exists in the U.S. A primary goal of Castañón’s is to help bridge that gap. Twice annually, he travels to Mexico to visit family—where his mom and six siblings still live—and always signs up for a race.

“I want to know the Mexican trail running culture and to learn how Mexican racers think. What are their questions, what can I learn, and what can I tell? I can share what I have learned in the U.S. When I started running, I made a lot of mistakes. When you have someone to help you, you can shine more,” he said.

For Castañón’s Hardrock debut, he registered as a U.S. racer. But later, he realized he could help strengthen the community of Mexican ultrarunners if he registered as a Mexican citizen, which he did for the Barkley Marathons as his second Hardrock.

“I’m trying to be a role model for Mexicans and to inspire them to not be afraid to try new things. I want to teach them it’s possible, that you just need to do your homework. I’m an average runner, and I’m able to share trails with first-class runners like Kilian Jornet,” he said.

Ultrarunning coach and writer Sarah Lavender Smith first connected with Castañón close to eight years ago. They started bumping into each other at ultras, including Hardrock, and had mutual friends in the northern California running scene where they both then lived. She’s watched Castañón’s influence grow over the years. “Noé is an influential ambassador in the Mexican-American community of long-distance runners, raising awareness in North America about Mexico’s ultrarunning scene, and encouraging Mexican ultrarunners to train and race internationally. I appreciate his bilingual social-media posts, which enhance my knowledge about ultras he’s run while also prompting me to brush up my Spanish reading skills,” said Smith.

In 2011, tragedy struck again. Castañón’s Bay Area home burned down in a domestic fire caused by lit candles. The night of the incident, Castañón was running a 200-mile team relay race. He and his wife—who was unharmed—lost everything they owned, including their two beloved dogs who passed away in the blaze. With support from the American Red Cross, the couple stayed in a hotel for four nights as they searched for a temporary rental. It would be eight months before their home could be rebuilt. “Dealing with the insurance was a huge nightmare,” recalled Castañón.

The day after the fire, Castañón’s relay team pooled together their resources to give him the basic necessities like clothing and footwear. “The run community was really good to me. I felt blessed to have them on my side. After the first month of being homeless, I still had a job, and my wife and I were healthy, so little by little, we were able to be on our feet again,” he said.

Following the generosity of the running community during his time of personal crisis, Castañón felt compelled to give back more to others. The next year, he launched a nonprofit, Shoes for Runners, that collects new or used running gear and ships it to various running clubs and communities in Mexico.

“Many Mexican runners don’t have the basic gear or shoes [for running]. Some runners race with basketball shoes. Trail running gear in Mexico is expensive. It’s good to do something for others. It’s not what others can do for you, it’s what you can do for them,” he said.

Castañón loves to give back in general. On average, he volunteers for seven races and four trail-work days a year.

Says Smith, “Noé is a constant, cheerful, positive presence at ultras. He pops up everywhere. When he’s not running, he’s helping others at aid stations or by pacing. At my last 24-hour event in San Francisco on New Year’s Day of 2018, Noé showed up at daybreak, as if he could think of no better way to ring in the new year than by being with runners, and he began jogging by my side as I walked with fatigue. He began exhorting me with motivational sayings, ‘You can do this, you have the power within you! ¡Corre! ¡Fuerte!’ He wouldn’t let me walk. I ran an extra mile before the time limit because of him.”

Ultimately, Castañón’s work ethic and kind spirit is unparalleled in all he sets his mind to. He works Monday through Saturday, 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. at the auto mechanic, plus his long commutes, and plus his home responsibilities. Despite all this, he still makes time to train. He’ll finish ultras on Sundays and drive home to be back at work on Monday. After the 2017 Tor des Géants—his favorite race so far—he clocked back into work on time, albeit limping and tired.

The race makes a 200-plus-mile loop through the Italian Alps and climbs more than 78,000 vertical feet along the way. “In Tor des Géants, you pass steep, hard mountains. The views are stunning like Hardrock—but Hardrock is only 100 miles. This is twice the beauty with the views, and so much suffering but so much preciousness. When you pass the [high-mountain] villages, it seems like you’re living in another time. It’s amazing,” he said. Castañón finished the race in 2017 in 149 hours, 19 minutes. He ran it again, in 2018, but dropped at mile 122, due to injury.

During the toughest race moments, Castañón is most motivated by his nuclear family and boss, but for different reasons than you’d might expect. They motivate him because they tell him that he should quit ultrarunning altogether. “They all say, ‘You never win, you spend so much money, you’re not fast, and you don’t get paid.’ Their lack of support is a reality, but I don’t take it personally. I don’t need to prove anything to them,” he said.

Castañón’s boss wishes he’d stop racing so that he’s faster—rather than sore—on the shop floor. His mom and a handful of his siblings fixate on the risk that’s involved in the sport. “Ultrarunning can be dangerous and runners do get injured—I’ve been injured. They are worried that the sport is too much pressure on my body and that I might be harmed,” he said. His wife is not involved at all. “At my first race, she said, ‘This is boring, I don’t want to spend the whole day waiting to see if you can run this.’ I don’t want to force her to come with me, and that’s fine. I’m going to keep doing it,” he said.

In the beginning, his pursuit of ultramarathons led to disagreements between them. At races, his friends would be greeted by their family members, which he longed to experience, too. Now, Castañón and his wife have a peaceful acceptance of each other’s personal time. She likes to read, and he prefers to run. Between races, he uses social media to stay connected with the ultrarunning community. “Ninety-five percent of my friends on Facebook are runners. I’m always feeding my soul with running and my friends like what I do. That keeps me positive,” he said.

He also focuses on the joy of sharing his race experiences with other runners and occasionally, his brother. Castañón’s sister and two brothers still live in the Bay Area. They speak on the phone often and his brothers are always excited to talk with him about running. One of them, Elias, has crewed for many of Castañón’s 100-mile races. Recently, Castañón was surprised to see Elias lose weight. It turns out that he’d started running, too.

This year has been one of the toughest yet. His injury at last year’s Tor des Géants was a torn meniscus. Following his surgery last November, the recovery was supposed to take five weeks—but his knee took six months to heal. He’s only recently started to run again. With no mobility for that long period of time, however, he missed running, gained weight, and watched his friends celebrate at awesome races. But Castañón’s resilient, positive, and holistic perspective once again overcame the challenge.

“In my running career, I am thankful I’ve been in every race I’ve ever wanted to be in—in races that most people will never race. I tell myself, ‘You can’t always shine. You also need to watch and celebrate other peoples’ achievements. It’s important to volunteer and crew. It’s not just running that’s important, it’s also important that we are involved,” he said.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

Have you run with Noé Castañón at a race or on a training run? Or volunteered with him for trail work or on a race sidelines? Have you donated gear to his nonprofit? Leave a comment to share your Noé story!